Thoughts and Reactions

Starting Out

Don’t wait.

Akomfrah, 2015: 0.26s

There are no mistakes

Akomfrah, 2015: 0.31s

- Seize on any moment of inspiration, any idea, any train of thought when it arises

- Follow that through to where it leads

- Even if it doesn’t lead anywhere

- Allowing a moment of inspiration to pass could mean an idea is lost and cannot be resurrected

- Those ideas are Akomfrah’s ‘germinations’, the beginnings of ‘something’

Germination is the process by which an organism grows from a seed or spore. The term is applied to the sprouting of a seedling from a seed of an angiosperm or gymnosperm, the growth of a sporeling from a spore, such as the spores of fungi, ferns, bacteria, and the growth of the pollen tube from the pollen grain of a seed plant.

Wikipedia, 2024

Germination, the sprouting of a seed, spore, or other reproductive body, usually after a period of dormancy. The absorption of water, the passage of time, chilling, warming, oxygen availability, and light exposure may all operate in initiating the process.

Heslop-Harrison, J., 2024

- An artist has to learn to recognise the ‘germinations’, the earliest stages of an idea or a thought, however slight they may be, then nurture them, ‘water them’, ‘feed them’

- As those germinations progress, grow, develop, the artist has to identify when their value is increasing or decreasing, then decide on the most appropriate course of action from there: continue, or discard. Those value judgements can happen at any stage

- There are no mistakes when pursuing any creative ‘germination’: something will be learnt.

- Creativity is about recognising that, what societal ideological norms label as mistakes, are actually opportunities for learning, growth, redirection, reframed understanding, all of which can positively affect the development of an idea/ work

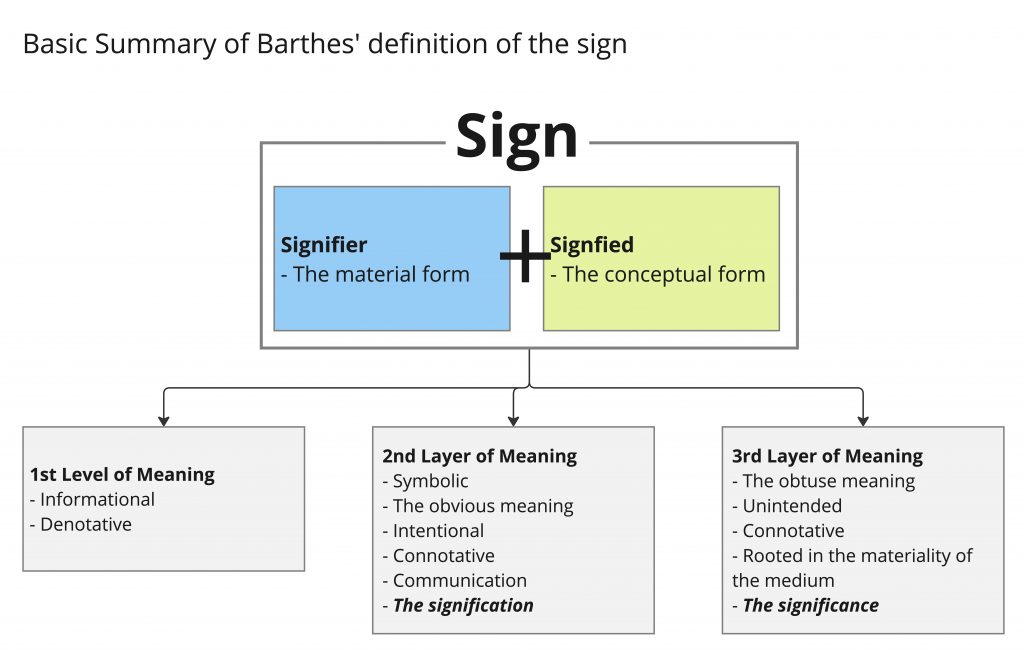

- It could be argued that the germinations and the ‘mistakes’ are how Akomfrah arrives at the ‘third meaning’, the ‘significance’ according to Barthes

Borders and Limits

- When Akomfrah talks of ‘borders’ and ‘limits’ I feel he is referring to where the current limit of creative practice has been defined as being at a point in time

- He is not looking at Tarkovsky’s films, particularly ‘Mirror’, and thinking “that’s the limit of what can be done” (my words). Rather, he’s asking himself how can he move past, better what Tarkovsky has created. He is looking at Tarkovsky’s work as an opportunity for learning.

- Part of artists responsibility is to see those limits and then push against them.

- That desire to push limits is the inertia that underpins a creative movement

- When an artist or group of artists recognise the limits of the creative zeitgeist, they seek ways to push beyond those to create new movements, new ways of working, to exploit new materials and new processes for creative expression

- As the world changes, ideologies become more entrenched, our understanding of ourselves and our needs becomes richer, the human race becomes, by turns more advanced and more backwards at once, as minorities challenge the oppression that suppresses their freedoms and needs, as the sustainability of the planet becomes ever more fragile – and every other change and development that is affecting us – artists have continually recognised the limitations of the defining practice of the time, and have sought new ways, processes, methods and materials of explaining the world around them

- Think of the uptake of film and video in the mid 20th century. Painting and sculpture was limited in how it could represent the strife inherent in the world at the time. The arrival of affordable, portable video equipment broke down the perceived limitations of the big studio movie and tv system, and allowed artists a mechanism for not just explaining the world, but rebelling against the entrenched oppressive ideologies pervading societies

- I think also of Greenberg’s powerful assertion around Modernism that ‘art should call attention to art” (Greenberg, 1960:775) and the specificity of painting, it should be ‘pure’ in that it should focus on the flatness of support (“It was the stressing, however, of the ineluctable flatness of the support that remained most fundamental”….”and so Modernist painting orientated itself to flatness as it did to nothing else”(Greenberg, 1960: 775)) and should eschew ideas (“which are infecting the arts with the ideological struggles of society. Ideas came to mean subject matter in general (subject matter as distinguished from content)” (Greenberg, 1940:564)). This was like a ‘red rag to a bull’ to artists, who sought to push the limits that Greenberg’s criticism imposed on the Institution of art at the time. Since that point, artists have appropriated a key philosophy of Greenberg’s, that The essence of Modernism lies, as I see it, in the use of the characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself” (Greenberg, 1960:774), not to entrench an artistic practice in its area of competence, but to push beyond those limitations imposed by “its area of competence” to maintain the underlying inertia of art’s, high-culture’s development.

Zones

- I originally equated Akommfrah’s zones to the medium – which in a sense they are – TV and cinema are mediums

- But these zones also need to be thought of more broadly; they are the channels via which, the places in which the artist’s ‘conversation’ with their audience is taking place

- In more basic terms, the places in which the artist’s work is displayed

- But that is too simplistic a definition as the situation of the work, its ‘channel of delivery’ can have a bearing on the process of creation, the piece’s content, the materials used, the physical nature of the work itself, and the audience who gets to see it: ‘Each has its own demands‘ as Akomfrah states in the video

- Akomfrah mentions the zones he works in: gallery, cinema, TV. But we can expand on those. Thinking of Banksy or Keith Haring’s, their zones would include sidewalks, building walls, subway billboards, clothing, sneakers, the human body, street signs. Rachel Whiteread – empty urban and rural spaces, rooftops. Early Damien Hirst – empty industrial spaces. Richard Serra – city streets. Christo – islands, urban landscapes, rivers. Richard Long – hills, fields, beaches

- The Zone the artist chooses to work in, to create work has a governance over the materials they choose to use, the process applied, the message communicated, the external factors – the demands Akomfrah speaks of – that need to be considered

- But which of these is the inception point for the work? There are some artists, particularly those entrenched in the gallery system, for whom the the space of delivery is the kick-off point. Then there are those, for whom the concept is the driving force, likewise, those who are focused towards their materials and process

- Akomfrah’s point is that from whatever point an artist begins their creative process of realisation, there will be a series of demands placed upon them, that they need to consider, that put in place borders and limits on what they can do, say, create etc. Those demands can also offer opportunities depending on the artists perception.

- Those demands will differ between zones

- He mentions ethical, political, cultural, aesthetic, but there are also the physical, emotional and mental demands of the making, financial demands, societal and ideological demands, audience demands, external stakeholder demands, material demands, process demands

The philosophy of montage

Dialetical: The ability to view issues from multiple perspectives to arrive at the most economical and reasonable reconciliation of seemingly contradictory information and postures. Dialectic resembles debate, but the concept excludes subjective elements such as emotional appeal and rhetoric.

Manzo, A.V., 1992

Bricolage is a French wording meaning roughly ‘do-it-yourself’, and it is applied in an art context to artists who use a diverse range of non-traditional art materials.

Tate, s.d.

- Akomfrah talks of his commitment to the dialectical philosophy of montage and how everyone who popularised this was interested in the ‘third meaning’

- There is a correlation between the concept of the ‘third meaning’, Barthes ‘significance’, and the dialectical philosophy of montage. I would argue that Akomfrah’s work is based on assembling and analysing a diverse range of opposing things (a dialectical bricolage if you like) allowing him to communicate his truth through, not just the informational, connotative or denontative around the subject or resources, but the also the significance inherent in his mediums (and their specific demands)

- Akomfrah seeks to reconcile his understanding, his perspective – the truth (?) – of history, by using a diverse range of images, sounds, ideas drawn from his extensive archive, to conduct a dialectical process within the physical boundaries of a screen

- He is assembling disparate and diverse imagery to present multiple perspectives with the intent of ‘engineering a synthesis’ that presents, overtly or subtly, a truth, a third meaning or what Barthes referred to as the ‘significance’

- And Akomfrah’s focus is the stripping away of all the ‘fictions’, the alternate perspectives told from the ‘victors’, the ‘oppressors’ standpoint, to present the reality of a lived experience

- An element of significance is determined by nature, quality and demands of the medium and the ‘zone’ (as Akomfrah puts it)

- Akomfrah’s dialectical approach encourages the ‘germinations’, embraces mistakes (they are germinations too).

Archive and documentary

An archive is an accumulation of historical records or materials – in any medium – or the physical facility in which they are located. Archives contain primary source documents that have accumulated over the course of an individual or organization’s lifetime, and are kept to show the history and function of that person or organization. Professional archivists and historians generally understand archives to be records that have been naturally and necessarily generated as a product of regular legal, commercial, administrative, or social activities. They have been metaphorically defined as “the secretions of an organism”, and are distinguished from documents that have been consciously written or created to communicate a particular message to posterity.

Wikipedia, 2024

A documentary film or documentary is a non-fictional motion picture intended to “document reality, primarily for instruction, education or maintaining a historical record”. Bill Nichols has characterized the documentary in terms of “a filmmaking practice, a cinematic tradition, and mode of audience reception [that remains] a practice without clear boundaries”.

Wikipedia, 2024

- I would suggest that all artists have an archive of sorts. For some it will be formally organised, supported by effective record keeping (such as Akomfrah’s) whilst others will have a more informal collection of records

- Akomfrah’s work is “characterised by their investigations into memory, post-colonialism, temporality and aesthetics and often explore the experiences of migrant diasporas globally.” (Lisson Gallery, s.d.)

- Archives are repositories of memories. As Akomfrah states, when viewing content from archives, we are “watching people who’ve gone” (Akomfrah, 2015), and that “image is one of the ways that immortality is enshrined in our psyche and our lives” (ibid)

- At this point we need to question the organising principles around an archive. We need to consider what influences have had a bearing on the information stored, the way it is stored, how it is accessed. Are archives independent of the curating organisation/ individual or the wider world in which they are situated? Information tends to be curated – or at least influenced – by the dominant political power, or society’s ideology. Archives can never be independent reflections of society

- I would suggest that by working with archives, by creating his own, by pursuing a dialectical bricolage based process that draws upon the contents of his archive to present an alternate view, a ‘lived experience view’, Akomfrah is challenging the dominant forces at play – the overt and tacit global conformity to structural white, privileged, patriarchy – in the telling of social narratives the world over

- The use of documentary is only one method he uses to disperse narratives. The ‘zone’ he decides to work in determines which method is most suited: TV – documentary. Feature films best for long format films. The gallery best for installations

Why history matters

List of illustrations

Fig.1. Panoramic view with figure in Mnemosyne (2010) [Film Still, Online Film] In: Mnemosyne UK: Smoking Dog Films

List of references

Akomfrah, J – Why History Matters (2015) [Online Video] At: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/sir-john-akomfrah-cbe-9259/john-akomfrah-why-history-matters (Accessed 24/07/24)

Greenberg, C (1960) ‘Modernist Painting’ in Harrison, C & Wood (eds.), P Art in Theory 1900-1990. An Anthology of Changing Ideas Oxford, UK & Cambridge, USA: Blackwell. Pp. 754 – 760

Heslop-Harrison, J (2024) germination At: https://www.britannica.com/science/germination (Accessed 28/07/24)

Lisson Gallery (s.d.) John Akomfrah At: https://www.lissongallery.com/artists/john-akomfrah (Accessed 28/07/24)

Manzo, A.V. (1992) Dialectical Thinking: A Generative Approach to Critical/Creative Thinking At: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED352632 (Accessed 28/07/24)

Tate (s.d.) Bricolage At: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/b/bricolage (Accessed 28/07/24)

Wikipedia (2024) Archive At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archive (Accessed 28/07/24)

Wikipedia (2024) Documentary At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Documentary_film (Accessed 28/07/24)

Wikpiedia (2024) Germination At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Germination (Accessed 28/07/24)