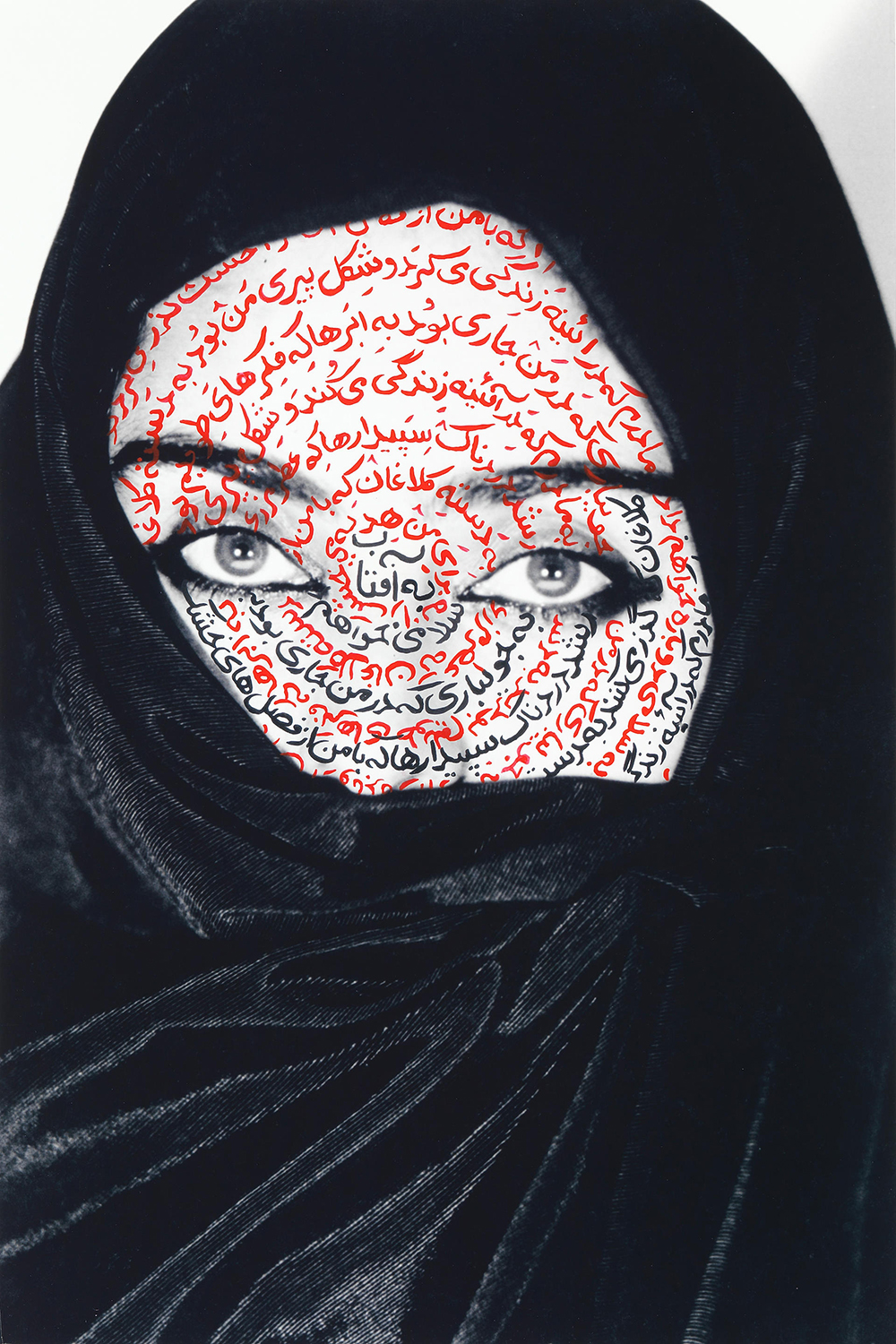

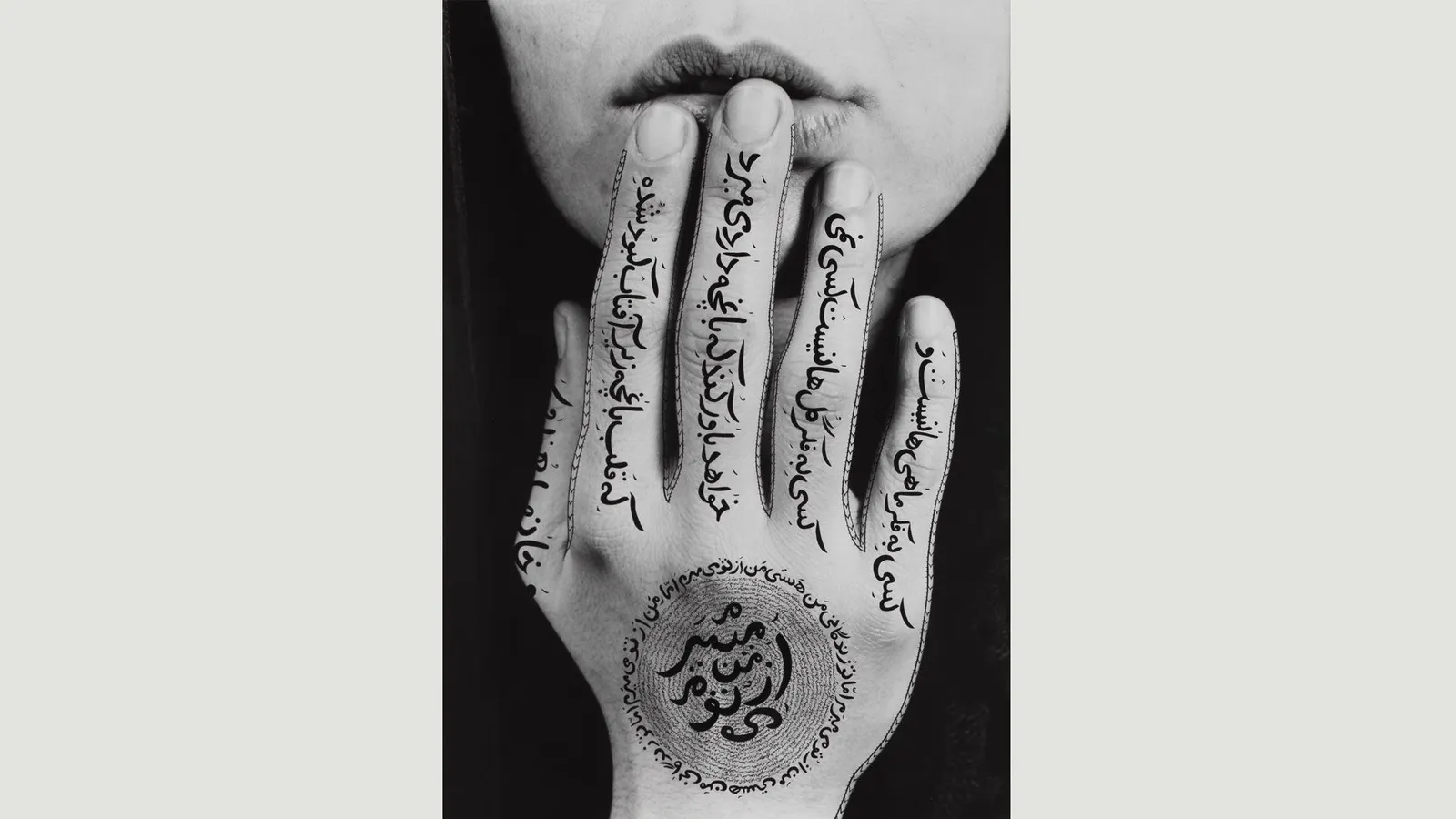

Fig.1. I am its secret (1993)

In their work, both Shirin Neshat and Jenny Holzer are confronting their societies governing ideologies from a place of feminist thought and observation, one from the duality of a diasporic Iranian-Canadian identity, the other, an American with a repressed spirituality (Heurta Marin, 2021).

Shirin Neshat

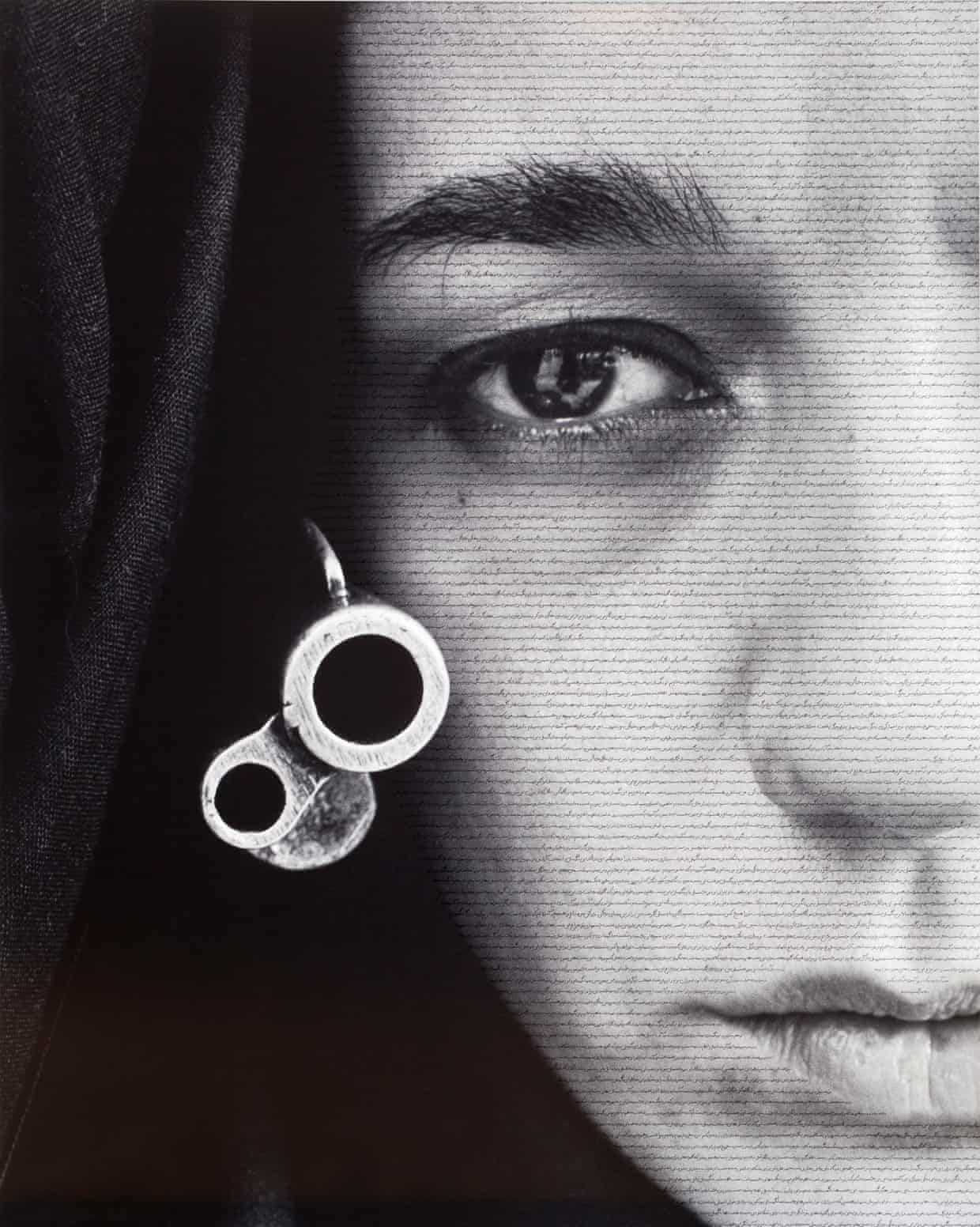

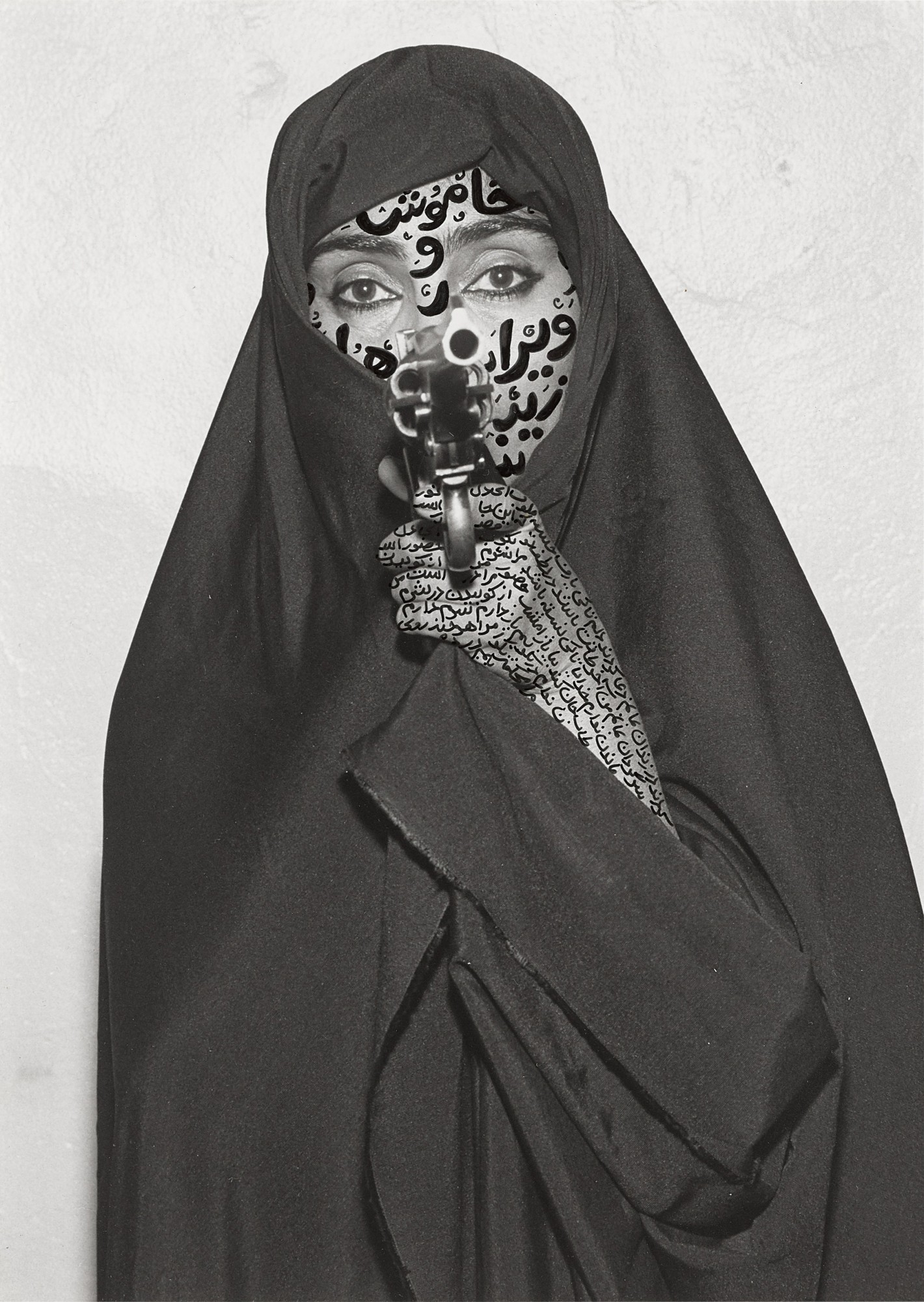

Fig.2. Speechless (1996)

Neshat’s series of photographs, ‘Women of Allah’, confronts the incumbent post-revolution, oppressive patriarchy of Iran with a “sustained rumination on the status and psyche of women in traditional Islamic countries” (MacDonald, 2004: 621). They directly address the position of women in relation to Islamic fundamentalism and militancy inherent in the country. And these images are also influenced by Neshat’s schizoid, diasporic identity (MacDonald, 2004:625) questioning ingrained western perceptions of Islamic nations and their treatment of women.

Fig.3. Faceless (1994)

Neshat’s high-contrast, predominantly black and white photographs are, by turns, intimate and confrontational. Ranging in size, from just less than A4 to circa A2, they show women (often Neshat herself) in traditional black dress, the faces often veiled, gazing directly at the camera, holding a weapon (primarily a gun), with the skin that is exposed seemingly covered in Farsi calligraphy.

Fig.4. Rebellious Silence (1994)

Neshrat’s discourse leverages four key signifiers of Islamic culture – the veil, the gun, the text and the gaze – to form her discussion on the contrariness of the status of women in her homeland. Starting with the veil, this is regarded as a symbol of oppression by the West, especially when viewed in light of “the simultaneity of the Islamic Revolution with women’s liberation movements in the U.S. and Europe, both developing throughout the 1970s” (Young, 2015). But in Neshat’s work, there is a duality of meaning when considering Feminism’s relationship to Islam. For Middle-Eastern women, “the veil is empowering and affirmative of their religious identities” (Young, 2015): it is liberation. It is also protection from becoming the sexualised object of the male gaze that is normalised in society – and in popular culture.

The directness of the subject’s gaze in the photographs is also a counter to masculine objectification: gazing back, especially with the calm confidence displayed in the photos, especially from an oppressed minority whose faces are often hidden or averted, is another means of freeing the female body from objectification and ‘centuries of subservience to male or European desire‘ (Young, 2015)

Fig.5. Stories of Martyrdom (1994)

From a Western viewpoint, the guns in Neshat’s work echo ideas of religious fundamentalism and martyrdom that instil an irrational, unnecessary fear of Islam into our more secular consciousnesses though there are deeper layers of meaning at play. They reference another level of female oppression, the ideological repression of their individuality and creativity in the support and sustenance of a revolution that frees them from Western decadence (MacDonald, 2004: 621), and they are also suggestive of the play of the male gaze: the gun shoots as the camera shoots, both violating women’s bodies. But they also suggest female empowerment: “We often think of women with an Islamic background as being passive and submissive to men, but here they were really empowered by bearing arms” (Neshat 2017 cited in Frizzell, 2017)

Fig.6. Untitled (Women of Allah) (1996)

As for the text, on closer inspection, it becomes clear that the Farsi calligraphy is inscribed directly on the photographs, and not on the body itself. In her essay, Begüm Özden Firat describes how this opens “up a medial space between the body and the writing that provides the images with multi-layeredness” (Özden Firat, 2006: 209) and that it is “among these layers that handwriting as a cultural practice reclaims its aesthetic, cultural and political reminiscence” (sic).

Again, the Farsi calligraphy is a highly loaded signifier towards the Quran, Sharia, to the repression nature of Islamic states or to Al_Jazeera tv news captions but again, as Özden Firat entreats us “By masking/ ornamenting her culturally hybrid body with the veil and the Arabic script of the Muslim Other, Neshat questions the Western viewer’s already constructed viewing position and attempts to turn the gaze upon itself to reflect on the cultural screen upon which these images are encouraged to be seen” (Özden Firat, 2006: 209).

The handwritten text suggests that there are different cultural perspectives for viewing the images, “at the intersections of the visual and the verbal, of looking and reading, of translation and unreadability: (Özden Firat, 2006: 210). This enables “multilayered interpretations by creating productive tensions first by appropriating and remediating the Islamic Calligraphy tradition on the visual plane, and second, by reclaiming the body both as a text that is culturally overwritten and as a medium that self-reflectively overwrites itself” (sic).

This multilayering is aided by the contrasting materiality of the ink against the photos. Though not apparent from the images in this research log, the ink stands proud of the smooth surface of the photographs, adding to the decorative interpretation of the calligraphy, in much the same way as the first stage of a henna tattoo on skin. This creates a space where the viewer not only wants to look, maybe to read (if they know Farsi), but also to touch the text, assigning the writing a synaesthetic dimension that normally only the writer themselves may access.

Özden Firat speaks of the “confusion of modalities of looking and reading” (Özden Firat, 2006: 210) in her essay. In this turn of phrase, the author is referencing the blurring of the boundaries between Islamic calligraphy as a system of writing for reading, and Islamic calligraphy as visual art, the way it is used and read, knowingly, as transmitting a linguistic message (sic), and visual art at the same time. Where it is used for more decorative purposes “Özden Firat speaks of the “confusion of modalities of looking and reading” (Özden Firat, 2006: 210) in her essay. In this turn of phrase, the author is referencing the blurring of the boundaries between Islamic calligraphy as a system of writing for reading, and Islamic calligraphy as visual art, the way it is used and read, knowingly, as transmitting a linguistic message (sic), and visual art at the same time. Where it is used for more decorative purposes “Özden Firat speaks of the “confusion of modalities of looking and reading” (Özden Firat, 2006: 210) in her essay. In this turn of phrase, the author is referencing the blurring of the boundaries between Islamic calligraphy as a system of writing for reading, and Islamic calligraphy as visual art, the way it is used and read, knowingly, as transmitting a linguistic message (sic), and visual art at the same time. Where it is used for more decorative purposes it tends “to subordinate the linguistic and semantic functioning to a visual function that invokes the aesthetics of writing and also that of the pleasure of looking.” (Özden Firat, 2006: 211). Where the calligraphy is used this way, it will suggest something of import to the pious Muslim, and will let the viewers conscious and unconsciousness fill in the blanks. This experience is beyond one of reading, becoming “an aesthetic experience that is collectively shared on the basis of a performance of cultural memory and as an enactment of individual revelation.” (sic)

Neshat accomplishes something similar in her ‘Women of Allah’ series. By calligraphing directly onto the photographs, and physicality of the materials and the words themselves, Neshat opens up an “an aesthetic scriptural space on the visual surface” which encourages that the writing can be both viewed and read, dependent on the cultural position of the onlooker. But a Western viewer is at a natural disadvantage if they cannot read Farsi, being forced to only look at the images as Neshat does not provide translations for the inscribed texts. As Özden Firat knowingly states “The act of reading is both promised and prevented,which creates a desire to read that will not be fulfilled.” (Özden Firat, 2006: 212). Because of their unreadability in some quarters, the “inscriptions on the photographic images encourage a diverse mode of signification rather than referring strictly to the linguistic” (sic). This renders the text in the same light as the veil and the gun, a generic visual sign open to (mis)interpretation, an interpretation that often leads to an assumption that the texts are drawn from the Quran, again heightening the expectation that these images are potential references to religious fundamentalism, oppression, terrorism.

The texts Neshat uses though, are taken from the work of famous Iranian feminist poets’s, and these are broadly critical of the Iranian patriarchy and the ideology of the Iranian Revolution. Because of the deliberate exclusion of translations, the viewer has no choice but to interpret the images “through an Orientalist discourse that defines the Muslim Other by means of historically constructed culturally mediated stereotypes.” (Özden Firat, 2006: 212) and this in turn suggest that it is “Western perspectives about the Muslim World that obscures the viewers eyes” (sic) from the truth of womens lives in Islamic cultures.

In Women of Allah’ the veiled female body as controllable object and target of patriarchal power “gains a different signifying power through the calligraphic inscriptions, which translate the body into a culturally engraved site of resistance.” (Özden Firat, 2006: 213). “The quoted inscriptions, in a subtle way, suggest that the feminine body has multiple cultural skins with multiple significations: the material veil, which both ‘erases and enforces embodiment’ (Moore 2002, 3) and the textual skin that overwritesthe body that both suppresses and enables the subject with creative agency and cultural identity” (Özden Firat, 2006: 214).

“The handwritten quotes from these ‘militant’ writers, then, imply that the culturally inscribed feminine body is not only a site for subordination and coercion but is also a space for creative and subversive processes. In this capacity, the images suggest that the viewer read the female body as a cultural text that is entirely overwritten, yet it is not the body of the victim anymore; it is a culturally inscribed body that is also a site of memory that remembers the repressed stories and does not shy away from showing it. (Özden Firat, 2006: 214)

Neshat also challenges her culturally hybrid multiple skins by writing over the image of her own body. It is less by means of (dis)guising her body as the veiled cultural other than by transcribing texts in her mother tongue over and over onto the image of her body that Neshat negotiates and appropriates her diasporic, or exiled, Iranian cultural identity. Writing is what carries culture in much the same way that handwriting identifies individuals. Nehsat’s work deals with both the personal and the cultural. (Özden Firat, 2006: 214)

Neshat’s practice of writing is directed more towards appreciating her diasporic difference through the performance of writing as an established cultural practice. As a result, handwriting becomes both the artist’s individual signature and a sign of her cultural hybridity. (Özden Firat, 2006: 215)

By writing onto the photographs “she manages to keep the handwriting authentic and directs attention towards the materiality of writing, and hence towards the body at work, the ‘hand’ of writing. As such, the lost body of the artist as the photographed or the photographer is brought back by the handwriting that carries the trace of the writing subject on the mechanically reproduced images. The subjectless gaze of the camera that turns the female body into an object of looking is countered by the writing subject and by its corporeal energy, stimulated by the rhythmic inscription of Arabic letters.” (Özden Firat, 2006: 215)

The rhythmic pulses of the letters, their morphing over time, the pressure of the pen, and the thickness of the ink that it leaves on the surface of the photographic image, refer to the artist’s body in labor in durée of its practical activity.

Jenny Holzer

Bibliography

Frizzell, N (2017) ‘Shirin Neshat’s best photograph: an Iranian woman with a gun in her hair’ In: The Guardian 5/01/2017 At: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/jan/05/shirin-neshat-best-photograph-iranian-woman-with-gun-in-her-hair (Accessed 28/09/24)

Heurta Marin, H (2021) ‘Jenny Holzer on a Life of Turning Public Spaces Into Art’ In: Lithub 25/10/21 At: https://lithub.com/jenny-holzer-on-a-life-of-turning-public-spaces-into-art/ (Accessed 28/09/24)

MacDonald, S (2004) Between Two Worlds: An Interview with Shirin Neshat In: Feminist Studies 30(3) pp.621-660. At: file:///Users/nikolashead/Downloads/Between_two_worlds_an_intervie.PDF.pdf (Accessed 28/09/24)

Özden Firat, B (2006) ‘Writing Over the Body, Writing With the Body: On Shirin Neshat’s Women of Allah Series’ In: Neef, S. et al (eds) Sign Here!: Handwriting in the Age of New Media. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp.206-220

Young, A (2015) Shirin Neshat, Rebellious Silence, Women of Allah series At: https://smarthistory.org/shirin-neshat-rebellious-silence-women-of-allah-series/ (Accessed 28/09/24)

List of Illustrations

Fig.1. Neshat, S (1993) I am its secret [RC print and ink] At: https://www.bonhams.com/auction/16680/lot/60/shirin-neshat-iran-b-1957-i-am-its-secret/ (Accessed 29/09/24)

Fig.2. Neshat, S (1996) Speechless [RC print and ink] At: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/jan/05/shirin-neshat-best-photograph-iranian-woman-with-gun-in-her-hair (Accessed 29/09/24)

Fig.3. Neshat, S (1994) faceless [RC print and ink] At: https://smarthistory.org/shirin-neshat-rebellious-silence-women-of-allah-series/ (Accessed 29/09/24)

Fig.4. Neshat, S (1994) Rebellious Silence [RC print and ink] At: https://smarthistory.org/shirin-neshat-rebellious-silence-women-of-allah-series/ (Accessed 29/09/24)

Fig.5. Neshat, S (1994) Stories of Martyrdom [RC print and ink] At: https://associazionegenesi.it/en/opere/stories-of-martyrdom-da-women-of-allah-serie/ (Accessed 29/09/24)

Fig.6. Neshat, S (1996) Untitled (Women of Allah) [RC print and ink] At: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20191104-shirin-neshat-a-stare-that-challenges-us-to-look-away