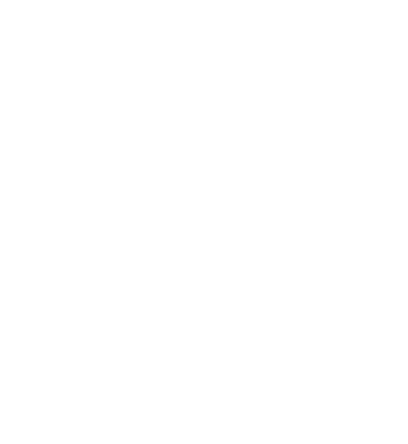

‘I Followed you to the end’ by Tracey Emin

Fig.2. I Followed you to the end (2024)

The titular painting from Tracey Emin’s most recent exhibition at the White Cube in London, is a confronting spectre of painted vulnerability and emotion, an image that transcends the fault line between painting and writing, producing – along with the other paintings in the exhibition – an almost diaristic exploration of her recent life’s most intimate and profound moments.

Even if you weren’t to know of the ‘transformative experience’ that fuelled the creation of this painting, the viewer is still made instantly aware that something visceral is at the heart of Emin’s motivation for creation. Executed in acrylic, seemingly rapidly, and measuring slightly under 2m tall, a ghostly suggestion of a female figure – the narrowness of the figure and the hint of breasts suggest femininity – dominates the centre of the painting. This figure seems to grow upwards and outwards from the canvas (is it a dress, a wedding dress they are wearing?) pushing into a tempestuous wind of crimson that swirls around the top half of the painting, which then rains in rivulets towards the bottom frame. But is that figure lying and painted from above, or is the viewer standing face-to-face with a vertical subject? The ambiguity of the subject’s orientation adds to the discomfort this painting engenders in the viewer.

Occupying just over a third of the lower half of the painting, Emin has inscribed a narrative in the same black acrylic as used for the figure. This is an exhortation that seems directed at specific men from Emin’s life, and yet, despite this apparent specificity, there is a triggering effect for those (especially men) whose only relationship to the artist is through her work.

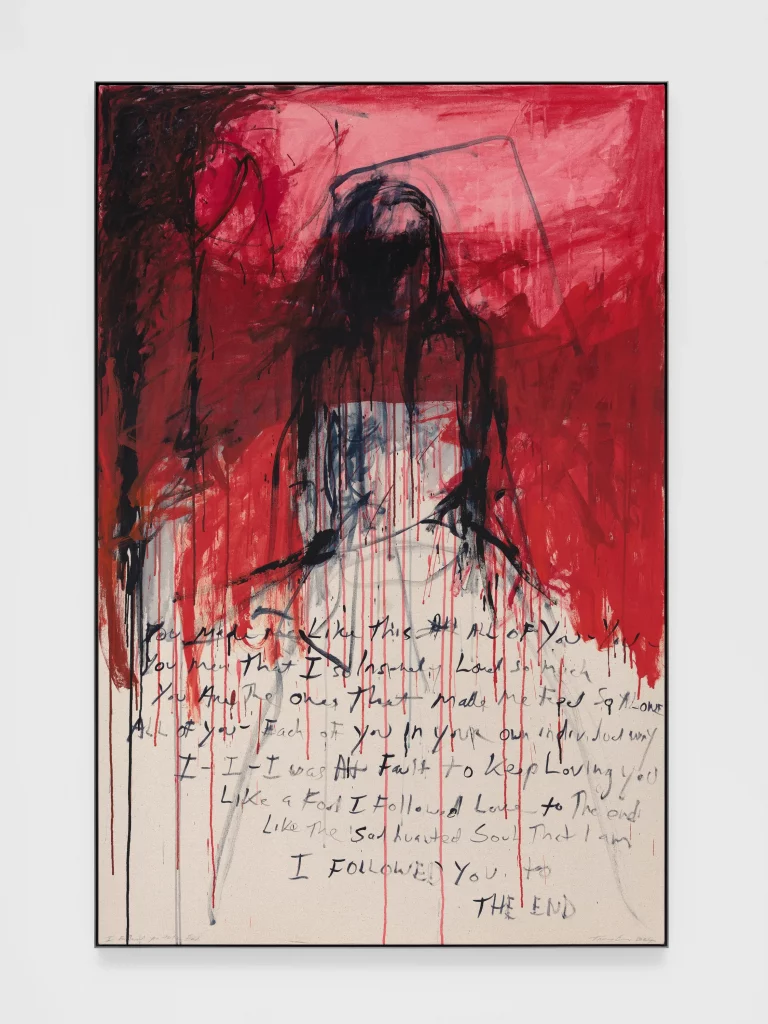

Fig.3. I Followed you to the end (Detail) (2024)

Emin’s written language is intrinsic to the materiality and the power of this painting, without it our response to the work would be different, lacking, less triggered: the words need the image and the image needs the words to function. With the materiality of the text being identical to that of the image, it is not possible to segregate the two by into discrete disciplines and the viewer subsequently unconsciously and naturally beholds the components as a whole. Materiality aside, I am then led to ask if the narrative element is painted or written in paint- is there a definable difference between the two actions? Is that a valid question to ask? Is writing actually a controlled form of painting, with its own set of standards or rules? The narrative element in this painting though does not reflect on a decorative function in the same way that the Farsi text does in, say, Shirin Neshat’s work does. Its primary relevance is in its meaning, what it states to the audience. Unlike Neshat’s work, where the form of the Farsi copy offers it’s own intrinsic aesthetic layer to the images for those who do not read the language, Emin’s copy cannot be appreciated in the same aesthetic way: it has a singular purpose – to directly and overtly deliver a emotional, confessional statement that both metaphorically and literally, underpins the figurative element of the painting.

The visceral confessionality of the narrative (and the painting) is heightened by the textual ‘mistakes’, the result of the immediacy of the writing-act (Emin states about the narrative component “I was quite angry about something – very angry actually. I started writing over the paintings, and I never knew what I was going to write. It’s just automatic (Emin, 2024 cited in Silver, 2024)). The writing ignores the standards we are taught in school, mixing lowercase with upper, excising punctuation and disrupting grammar. It’s layout beginning top-left, filling almost the width of the canvas, compresses towards the end, seemingly speeding the pace of the reader up as they progress through the confession to the abruptness of the ‘THE END’. And then, there is way that the presence of the letters fades in and out, from prominent to the barely there. All of this is powerfully suggestive of someone who is angrily focused on unburdening themselves and quickly before their sense of the emotional core of their message dissipates.

What the viewer (may) judge (against their learned standards) as textual incorrectness, is important to Emin’s self-expression, of vulnerability and her experiences. Though speaking about her earlier applique work Mad Tracey From Margate, Everyone’s Been There (1997), Issac Fravashi’s observations on Emin’s use of text remain insightfully relevant:

The words are not incorrect because they are not misspelled by accident. Emin challenges the linguistic system’s restraints by refusing to censor or ‘correct’ her writing so that her expression conforms to grammatical law, therefore she asserts and prioritises her own expression over a standard model of art or language. Emin produces ‘not a work of art for the sake of art, but for the sake of the progenitor

Fravashi, 2023

Fravashi also contends that Emin’s ‘textual confessionalism’ is a direct descendant of the confessional poetry of Anne Sexton, Robert Lowell and Sylvia Plath, poetry that “adopts a personal voice, colloquial style, and pulls from biography for inspiration” (Fravashi, 2023). Confessional poetry “‘exposed the family as a crucible of trauma, a site of emotional warfare that shapes the self, and frequently delved into the psychic wounds of childhood to uncover the secrets of adult distress” (ibid). Emin is following the lead of those Confessional poets by candidly writing about her life and the “virtually unmentionable kinds of private distress” she endured – sexual abuse, an emotionally absent father, alcoholism, the recent near death experience of cancer and the subsequent cystectomy and hysterectomy.

Though Confessional, Emin’s narratives still carry the weight of fictionalisation in the stories they tell. She herself has stated in an interview with Stephan Collishaw for Believer “With a lot of the things I’ve done, I certainly wouldn’t lay myself on the line and say that’s the absolute truth, because it’s my memory, and what happened between that moment ten or fifteen years ago and now… there’s a lot of gray area. What matters is how I choose the material and put it together. As far as truth is concerned it’s very difficult to say what is and what isn’t true. What is truth? Truth doesn’t really exist. Who is going to judge whether my experience of an incident is more valid than yours?” (Emin, 2004 cited in Collishaw, 2024). It is this straddling of truth and fiction that contributes to her work’s ability to connect with its audiences.

In the end, all Tracey Emin has is herself. And that is a great subject. Her art is serious because it focuses relentlessly on one person’s joy and anguish. She never walks away from an emotion or memory. There is heroism to her refusal to look away from the simple truths of life, love and time.

Jones, 2020

‘Untitled (Charles Darwin)’ by Jean-Michel Basquiat

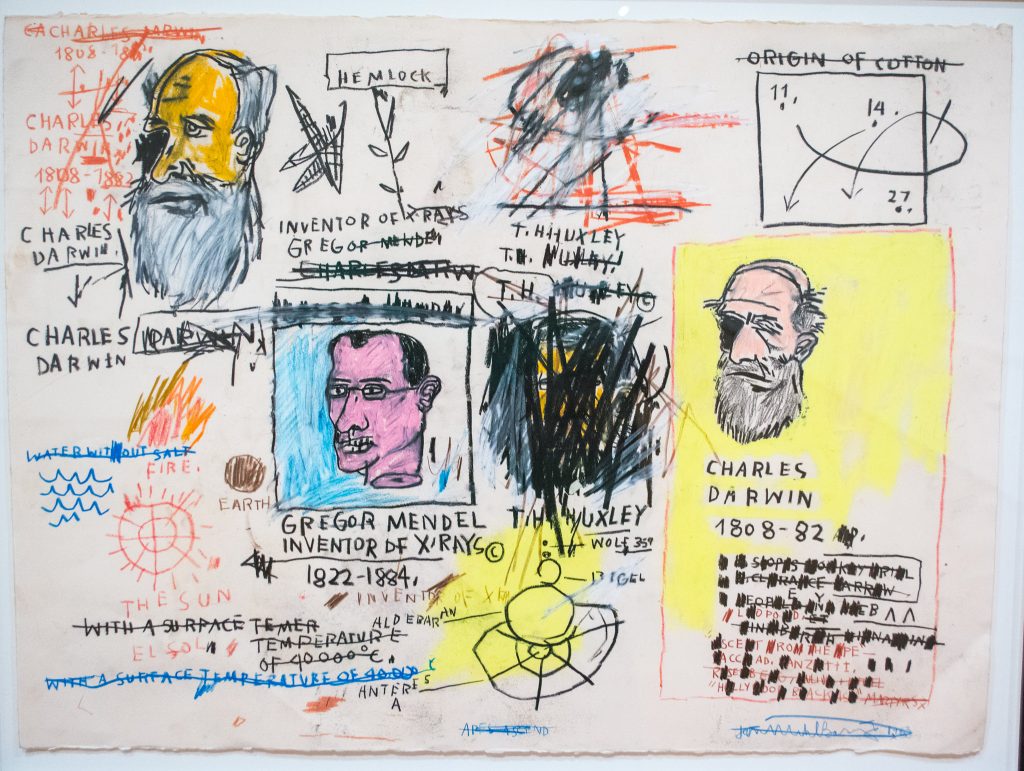

Fig.4. ‘Untitled (Charles Darwin)’ (1983)

Basquiat’s work is less confessional, more observation and commentary concerning the deeply embedded white-led, patriarchal systems of privilege that impacted him during his lifetime. As Robert Storr states “Basquiat’s mind was as prepared as his hand. That preparation combined a painful receptivity to the everyday experience of race, class and cultural tensions – not least of which were the internalized tensions of his own mixed Haitian-Puerto Tican lineage, but also economically “privileged” heritage” (Storr, 2010: 99)

‘Untitled (Charles Darwin)’ incorporates pictographic portraits and text to examine the theories of racial evolution. Towards the top left of the drawing is the first drawing of Darwin, grey bearded, sporting what could be construed as an eyepatch. Darwin’s name is labelled towards the bottom left of this portrait, reinforcing our understanding of who is being pictured. Just offset from the centre of the drawing a decapitated portrait of Gregor Mendel floats within a box, below which his named is inscribed in capital letters, followed by the phrase ‘INVENTOR OF X RAYS ©’.

To the right of Mendel’s portrait but obscured by rigorous scribbles, is a portrait of T.H. Huxley, beneath which is the name of several stars , some crossed out, one, Wolf 359, not. And then, on the right of the paper, a second portrait of Darwin, now looking somewhat haggard with thinning hair, still sporting the apparent eyepatch. Now, his dates of birth and death are visible (though the birth-date is incorrect) and below those are sentences disrupted by crossings out and individual black blocks. And then, across this drawing, acting as sorts of narrative signposts that connect and direct the viewer through the pictographic content, are various sentences or words, some with lines drawn through them.

When pragmatically Digging into the histories of the three scientists Basquiat has chosen to represent, apparent inconsistencies, mistakes surface. Gregor Mendel was a biologist who gained posthumous recognition as the father of the modern science of genetics – Basquiat’s literary assertion that he was the inventor of X-rays a glaring mistake. Then, the obscured T.H. Huxley, again a biologist as well as an anthropologist, a fervent supporter of Darwin’s theories – has no obvious connection to astronomical matters.

List of References

Collishaw, S and Emin, T (2004) An Interview with Tracey Emin At: https://www.thebeliever.net/an-interview-with-tracey-emin/ (Accessed 02/11/24)

Jones, J (2020) ‘Olympia’s Brush: Paintings and Drawings of the Nude’ in: Jones, J Tracey Emin London: Laurence King

Fravashi, I (2023) The Confessions of Tracey Emin At: https://decoratingdissidence.com/2023/04/07/confessions-tracey-emin/#_edn3 (Accessed 02/11/24)

Silver, H. (2024) ‘This blood that is flowing is my blood, and that should be a positive thing’: Tracey Emin at White Cube. At: https://www.wallpaper.com/art/exhibitions-shows/this-blood-that-is-flowing-is-my-blood-and-that-should-be-a-positive-thing-tracey-emin-at-white-cube (Accessed 02/11/24)

Storr, R (2010) ‘What Becomes a Legend Most’ in: Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Dieter Buchhart (Eds.) Basquiat Berlin: Hatje Cantz Verlag

List of Illustrations

Fig.2. Emin, T (2024) I Followed You to the End [Acrylic on Canvas] At: https://www.whitecube.com/artworks/i-followed-you-to-the-end-2 (Accessed 26/10/24)

Fig.3. Emin, T (2024) I Followed You to the End (Detail) [Acrylic on Canvas] At: https://www.whitecube.com/artworks/i-followed-you-to-the-end-2 (Accessed 26/10/24)

Fig.4. Basquiat, J.M. (1983) Untitled (Charles Darwin) [Painting] In: Buchhart, D (2017) Basquait. Boom for Real. London: Barbican Centre, Prestel. p. 220