Undeterred by deafness and blindness, Helen Keller rose to become a major 20th century humanitarian, educator and writer. She advocated for the blind and for women’s suffrage and co-founded the American Civil Liberties Union.

Michals (2015)

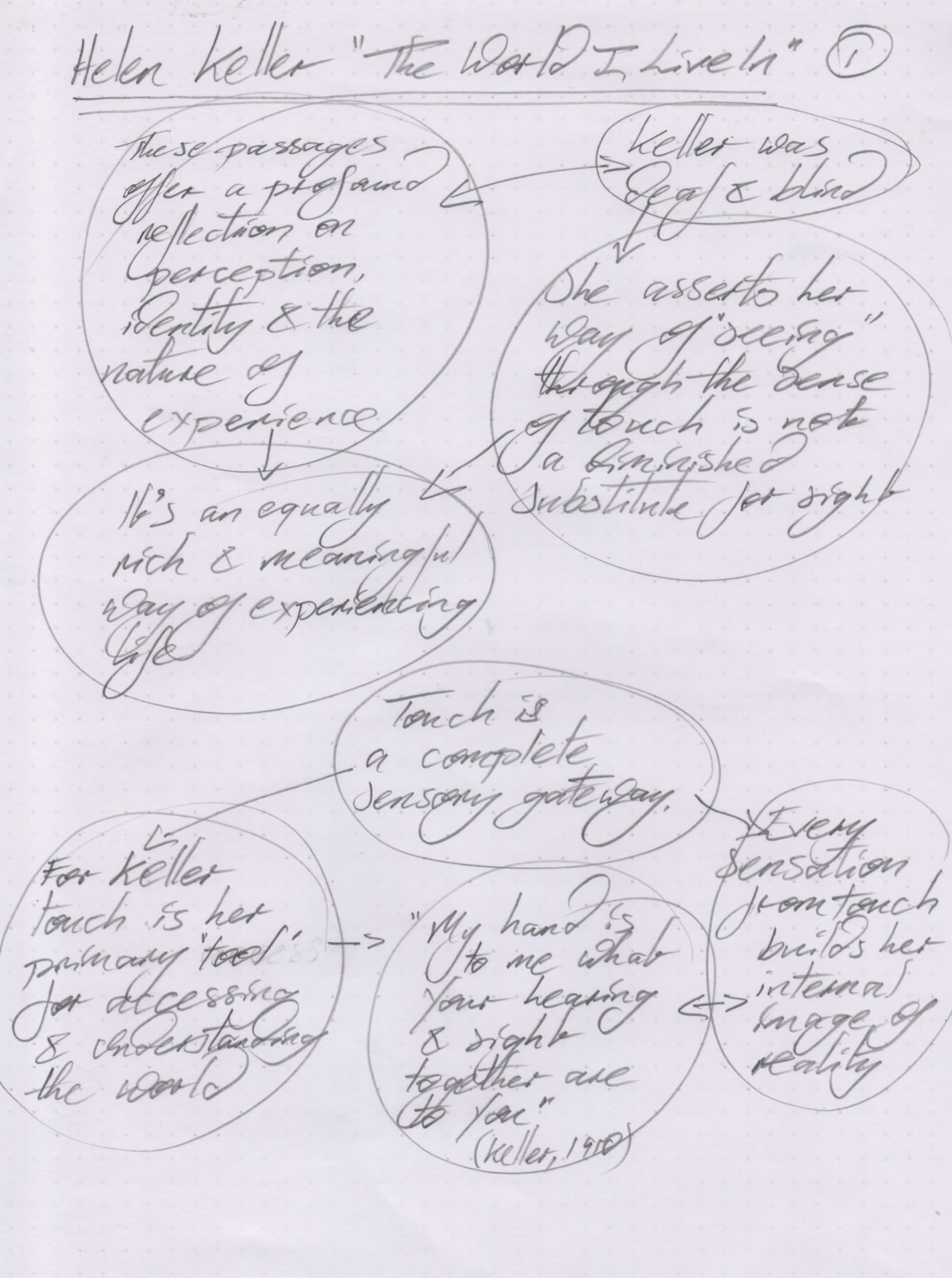

Keller’s work, “The World I Live In”, shares her reflections of her life as a deaf-blind person, exploring themes of perception, identity and the power of the human condition (Gutenburg, 2024). The underlying sentiment of this memoir, though, is her assertion that her life should not be judged against the ‘rules and standards’ of the sighted and hearing able, and that it is as rich, if not richer, specifically because of her means of interacting with the world. Keller’s memoir, as with her other writing, stands as a beacon for those that are minoritised for what normative ideologies define as ‘disabilities’, by delivering a powerful – but not polemical – challenge to structural perceptions of what it means to live a meaningful life.

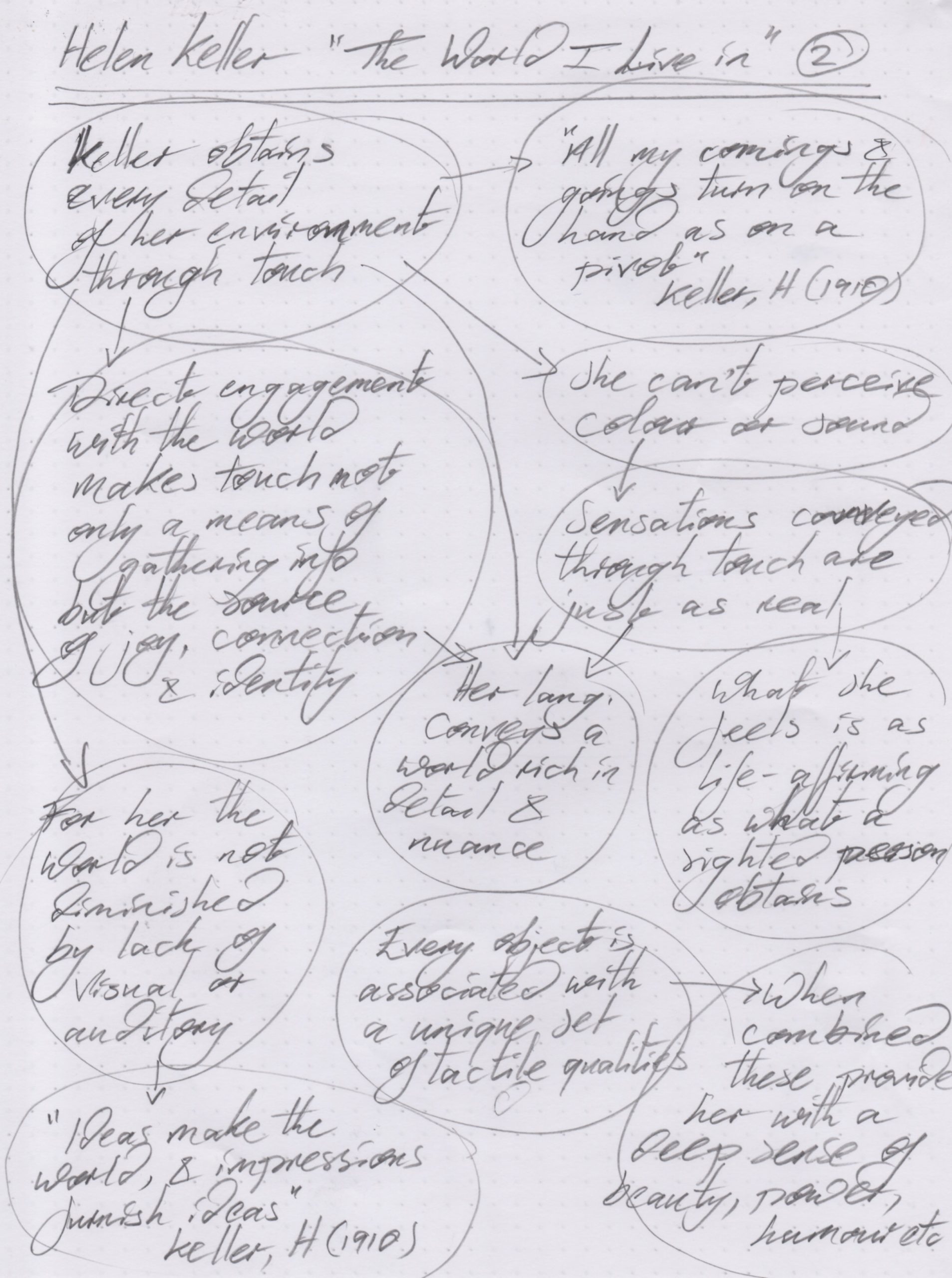

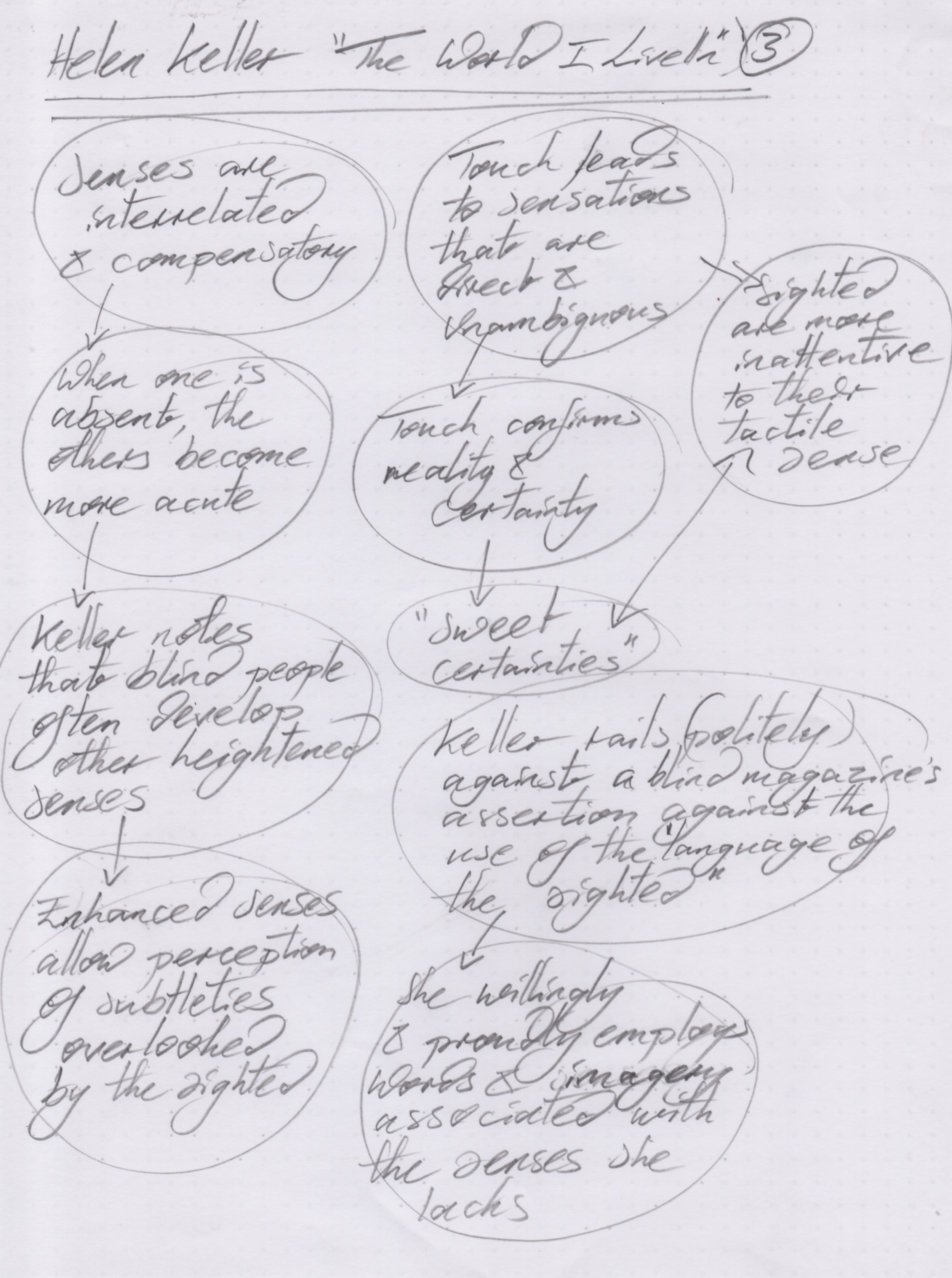

In the extracts featured in Documents of Contemporary Art: Translation, Keller discusses touch as her primary gateway to experience, asserting that her hand serves the role that sight and hearing do for others. In her vivid language, every tactile sensation—from the flutter of fingers to the delicate feel of petals—constitutes her reality. She draws upon her personal, lived experience to depict a world that, though devoid of visual colour and sound, is full of life and meaning. Through metaphors and analogies drawn from her intimate encounters, Keller transforms physical touch into an expressive and essential language of perception.

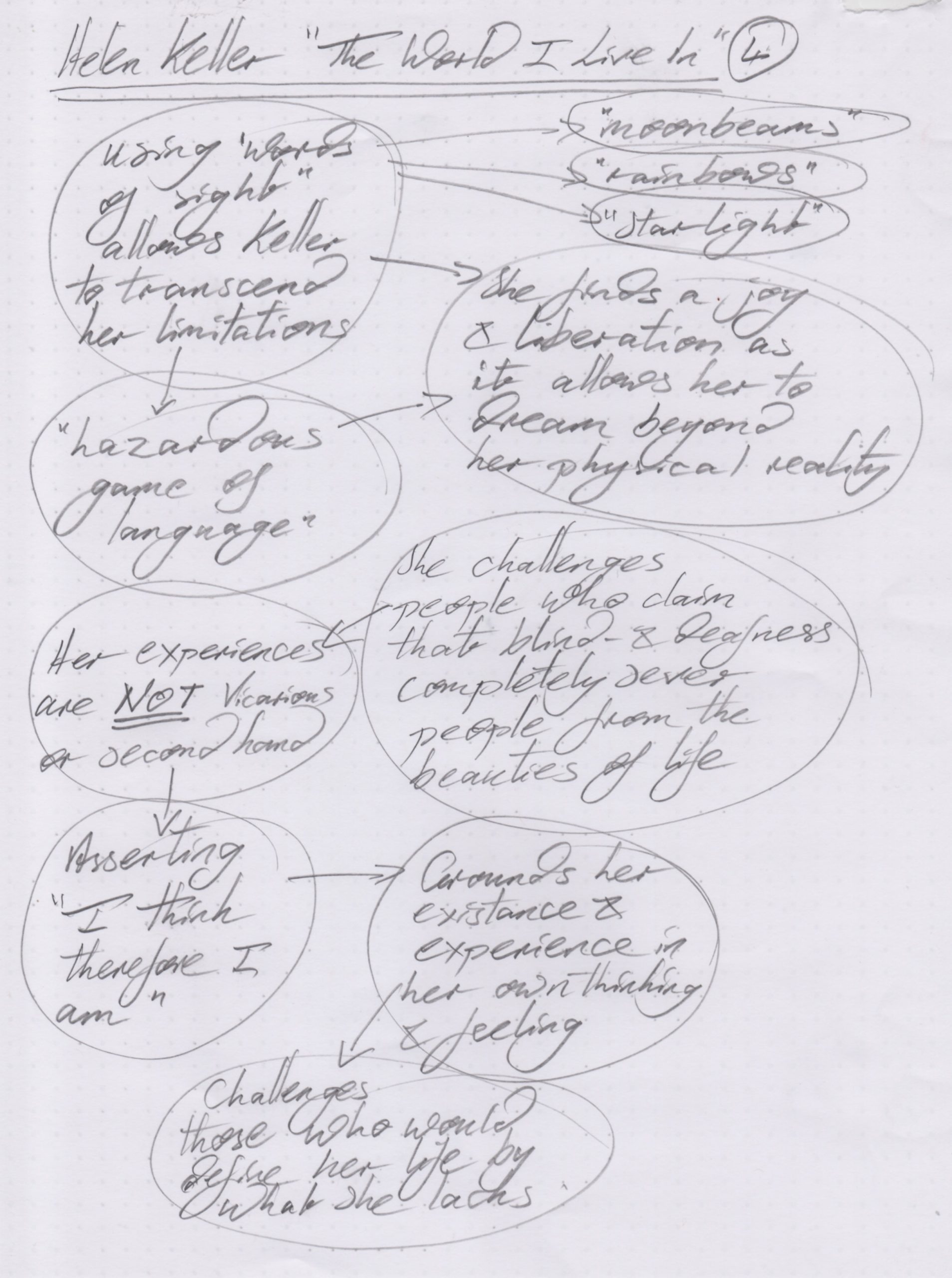

Keller’s deliberate use of words typically associated with sight and sound—such as “moonbeams” and “clouds”—reveals her creative adaptation of language to bridge her sensory gaps. By borrowing imagery from the cultural and historical lexicon of the sighted, she not only enriches her narrative but also challenges the confines imposed by her blindness. This playful “hazardous game” of language becomes a form of literary defiance, where the borrowed symbols of visual beauty extend her inner life beyond physical limitations, reflecting both her cultural memory and intellectual curiosity.

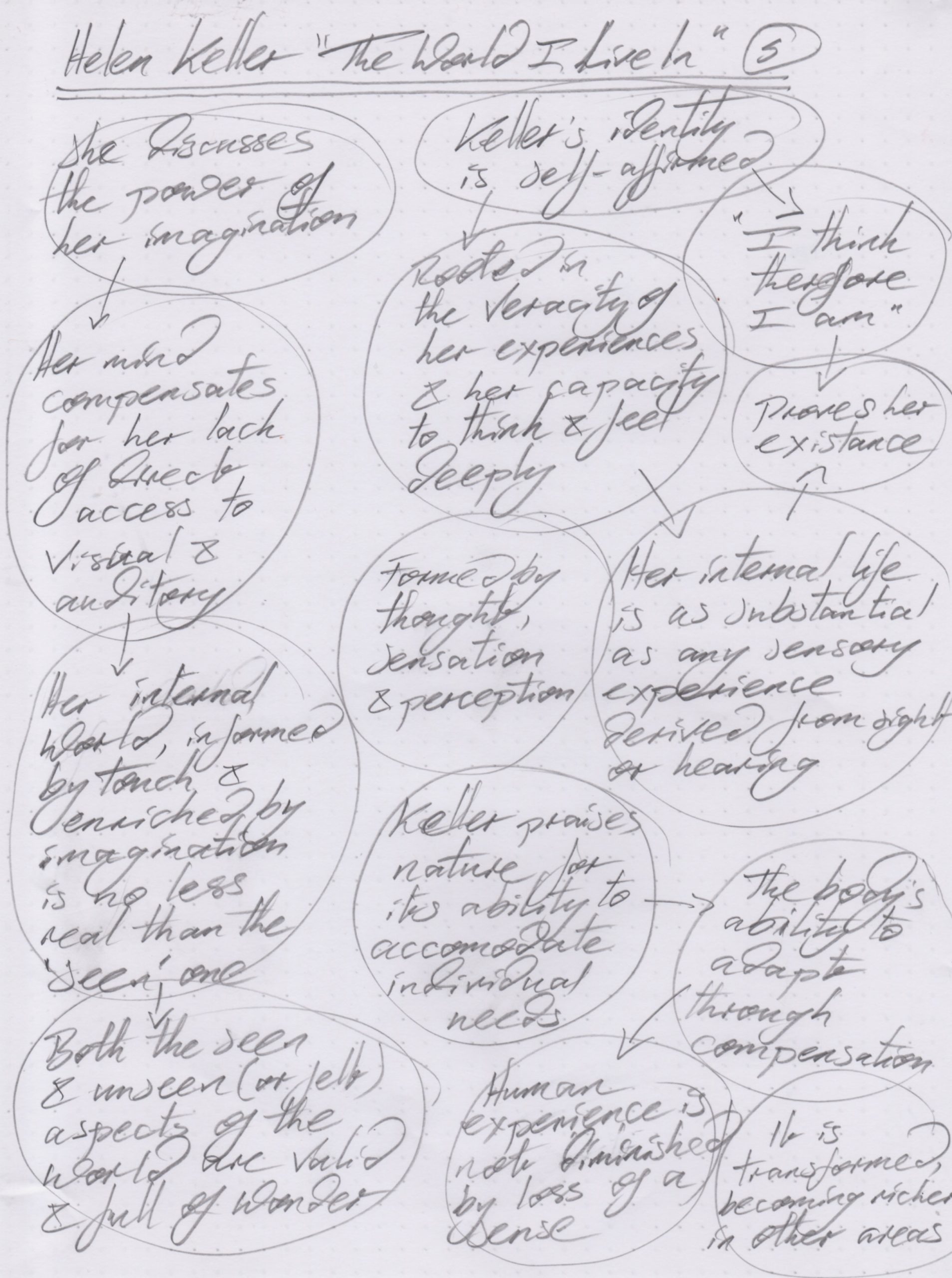

In addressing critics and societal expectations, Keller confronts the narrow definitions of sensory experience. She rebuts the idea that blindness and deafness disqualify her from discussing beauty or the sublime, arguing that her tactile encounters are as real and profound as any visual or auditory perception. Invoking Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am,” she asserts her existence and intellectual legitimacy against those who claim that her sensations are merely “vicarious.” This confrontation not only underscores her personal struggle against prejudice but also reflects a broader historical debate about the nature of knowledge and perception.

Finally, Keller explores how necessity has honed her remaining senses, transforming isolation into a dynamic engagement with the world. Her prose, rich with metaphor and sensory detail, mirrors the complex interplay between the physical act of touching and the expansive realm of ideas it inspires. The format of her writing—fluid, introspective, and interlaced with personal memory—supports her content by subverting the traditional privileging of sight. In doing so, Keller not only questions conventional sensory hierarchies but also elevates the tactile as a vibrant and complete means of knowing, inviting readers to experience beauty through an entirely different lens.

Research Notes

List of References

Project Gutenberg (2024) ‘The World I Live’ in by Helen Keller At: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/27683 (Accessed 09/02/25)

Michals, D (2015) Helen Keller At: https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/helen-keller (Accessed 09/02/25)

Bibliography

Keller, H (1910) ‘The World I live In’ In: Williamson, S (ed) Documents of Contemporary Art: Translation. London: Whitechapel Gallery. pp. 52-54