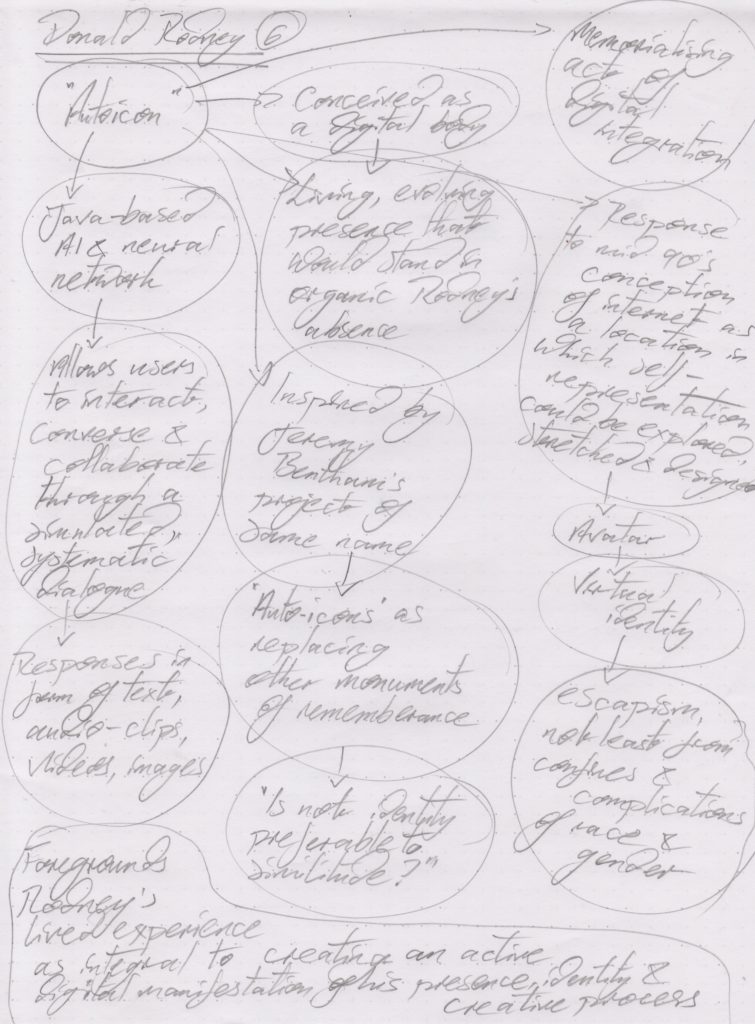

Memorialising Corporeality as an Act of Care in the work of Donald Rodney

When people pass away, the grieving are left to remember them the (often) un-curated artefacts they leave behind. This memorialisation is a tender act of care, to keep the deceased present in our daily lives, though in truth it only ever creates a fading, imperfect echo of the person’s essence. It never truly addresses the missing corporeality of the person that once was.

Artists, though, offer us a more profound means of memorialising their presence after death. And that memorialisation becomes especially poignant when we understand that the artist was acutely aware of their own mortality. As was Donald Rodney.

Whilst Rodney’s practice critically examined black identity and structural racism through the lens of Sickle Cell Anaemia, he also created a discursive memorial to his own physical existence that transcends typical remembrance, capturing a deeply personal yet universally resonant experience of embodiment and loss.

Throughout his career, Rodney’s condition provided him an emotive palette for his art, recording his corporeality by documenting his illness and associated medical experiences. Works such as ‘Flesh of my Flesh’ that used aestheticised medical imaging to make the interior of his body visible, and ‘In the House of My Father’ which literally incorporates his physical – tiny pieces of skin removed during surgery – catalogued his hospital stays, treatments and medical paraphernalia that were part of his lived experience.

But it is two pieces, involving then emerging new technologies, one created just before his death and another posthumously, that allowed him to leave a deeper, more involving echo of his presence.

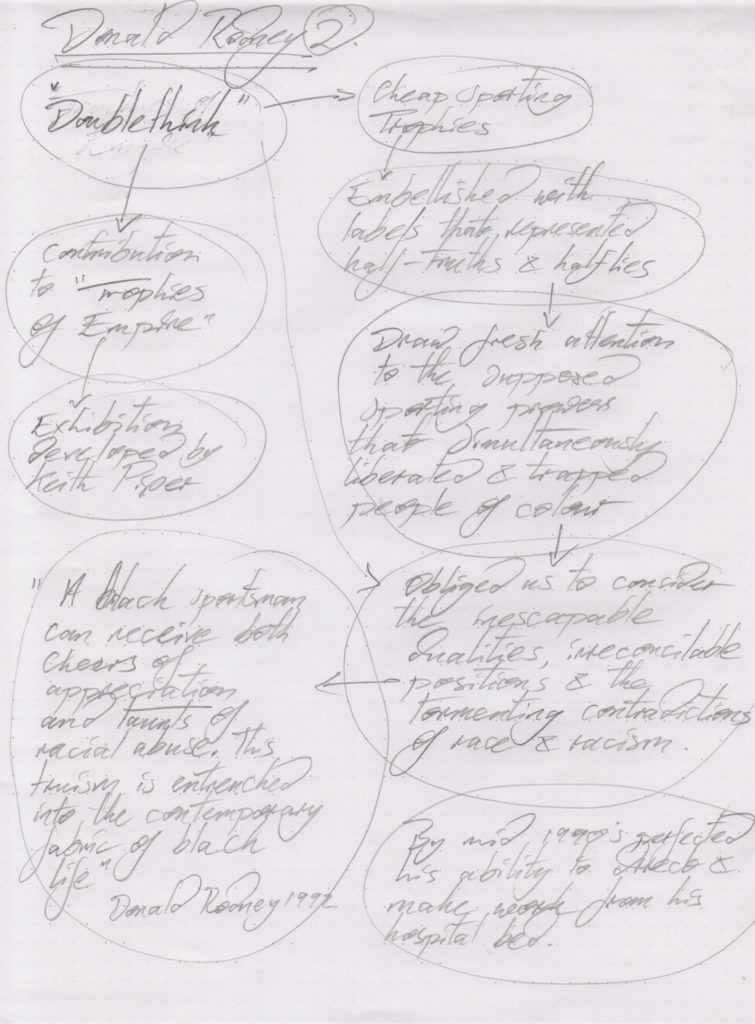

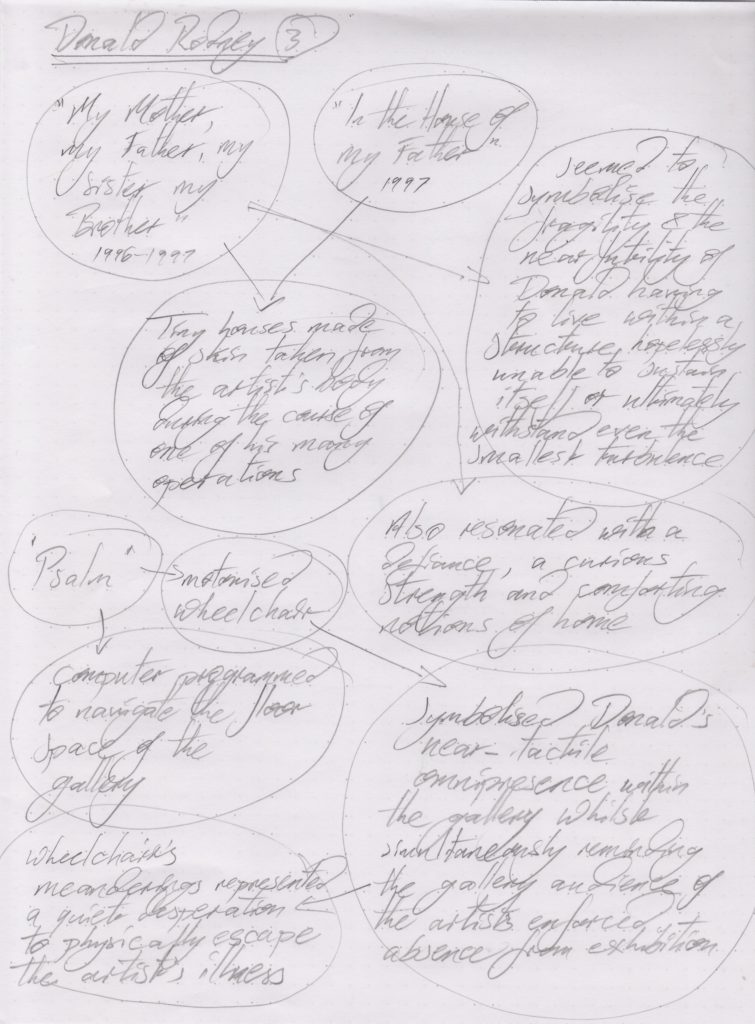

Fig.1. Psalms (Atlantic Project, Plymouth 28 September – 21 October 2018). (2018)

Fig.2. Psalms is the Autonomous Wheelchair constructed by Guido Bugmann for Donald Rodney’s “Nine Night in Eldorado” at the South London Gallery, 1997 (2016)

1997’s ‘Psalms’, created collaboratively just months before his death, reflects on Rodney’s physical frailty and his eventual absence. An autonomous, empty motorised wheelchair, created to articulate his presence – or lack of – at the opening of the exhibition ‘Nine Night in Eldorado’ “courses through its various trajectories on a sad and lonely journey of life, a journey to nowhere. Its movements repeat like an ever-recurring memory, a memory of life and another journey, that of Donald Rodney’s father” (Bilton, 1997 cited in Conway, 1997)

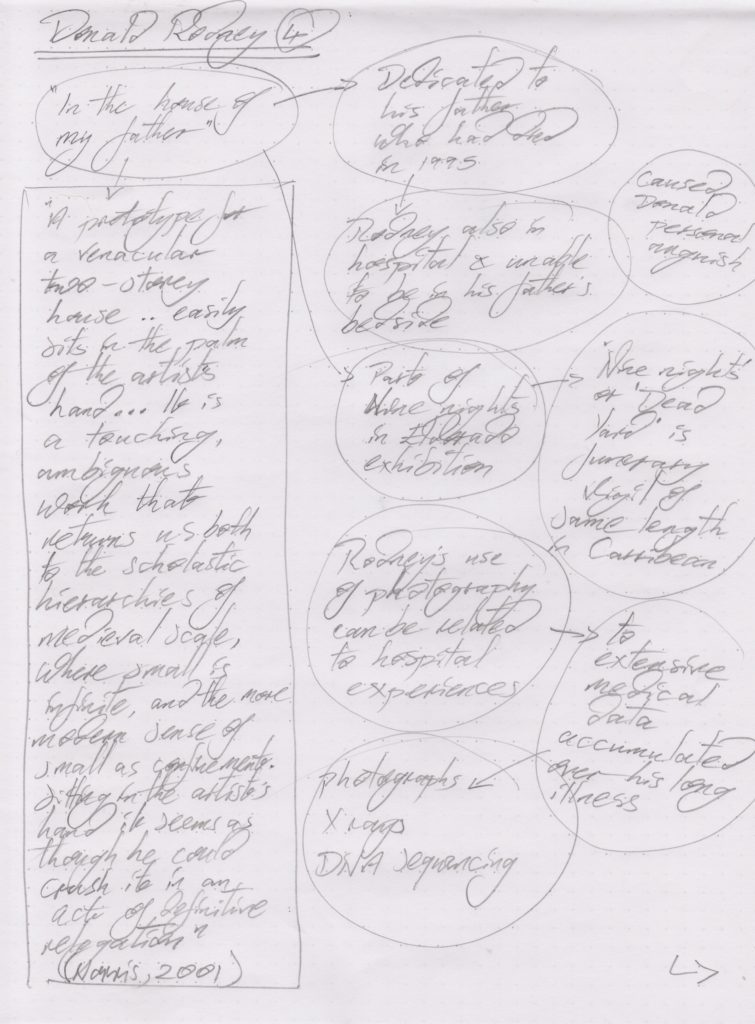

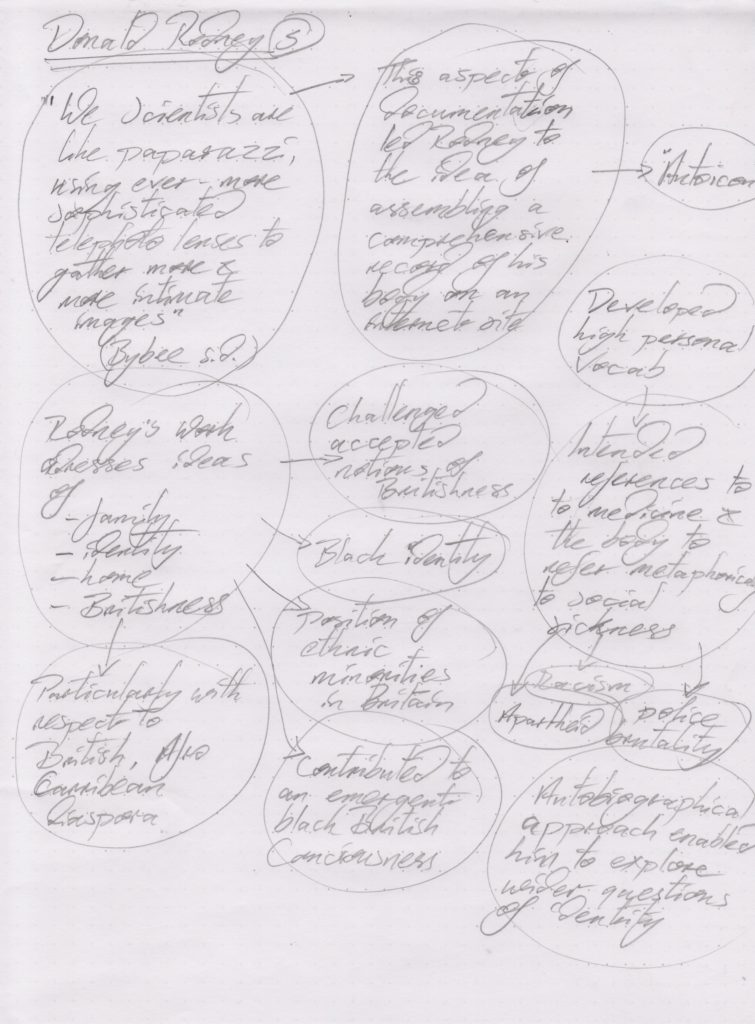

Fig.3. Autoicon (2000)

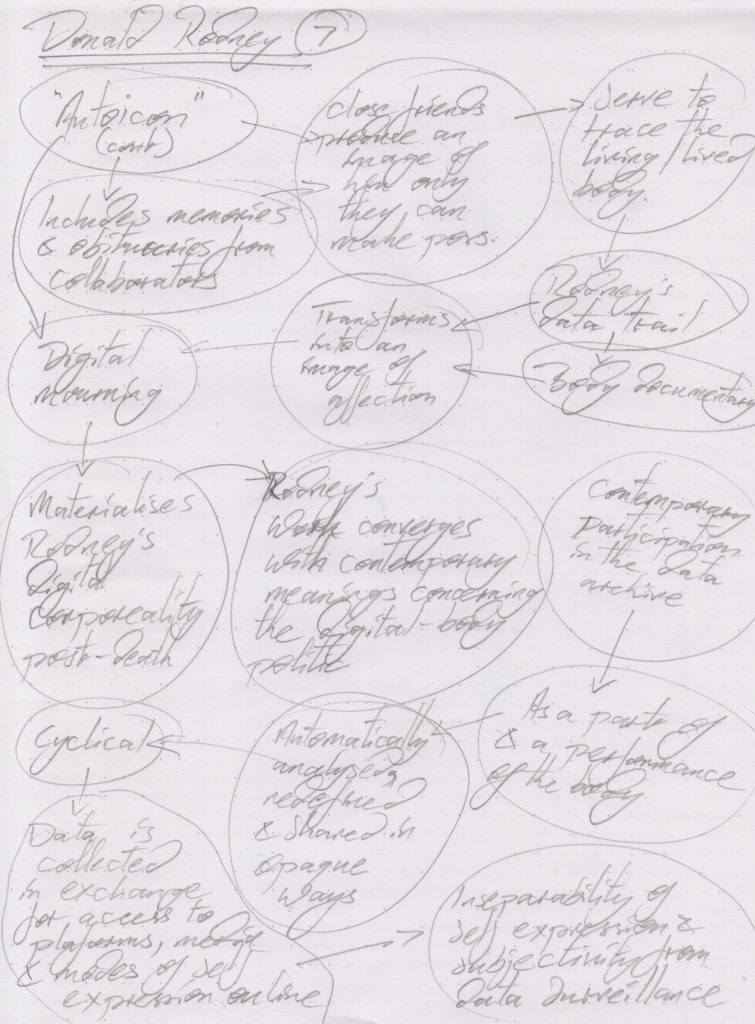

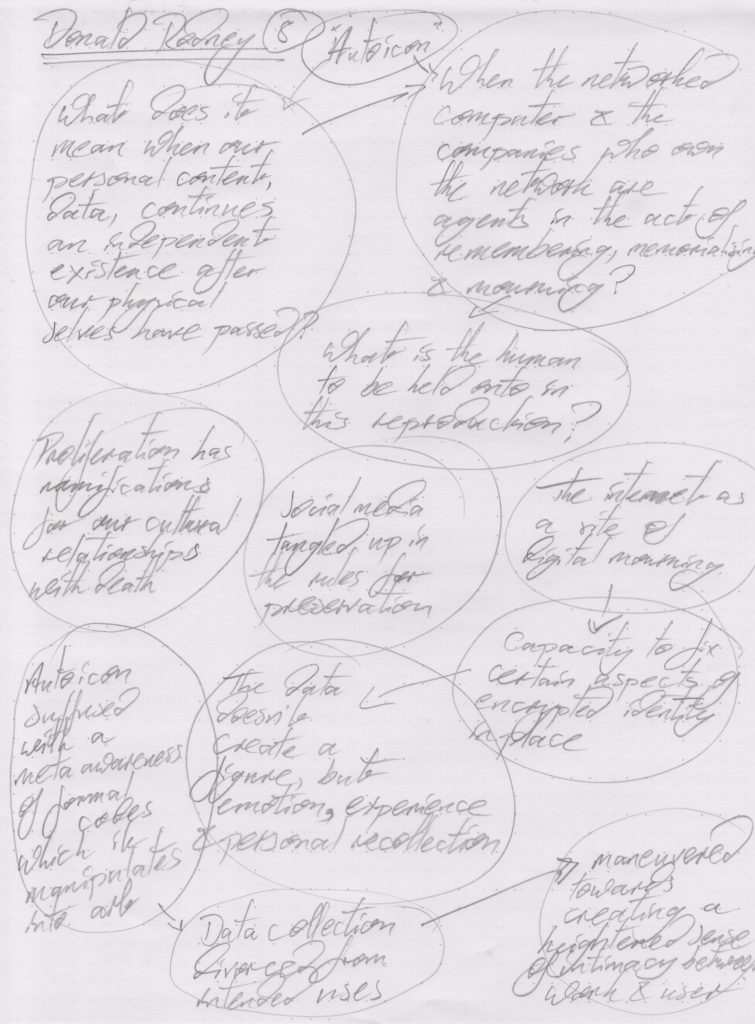

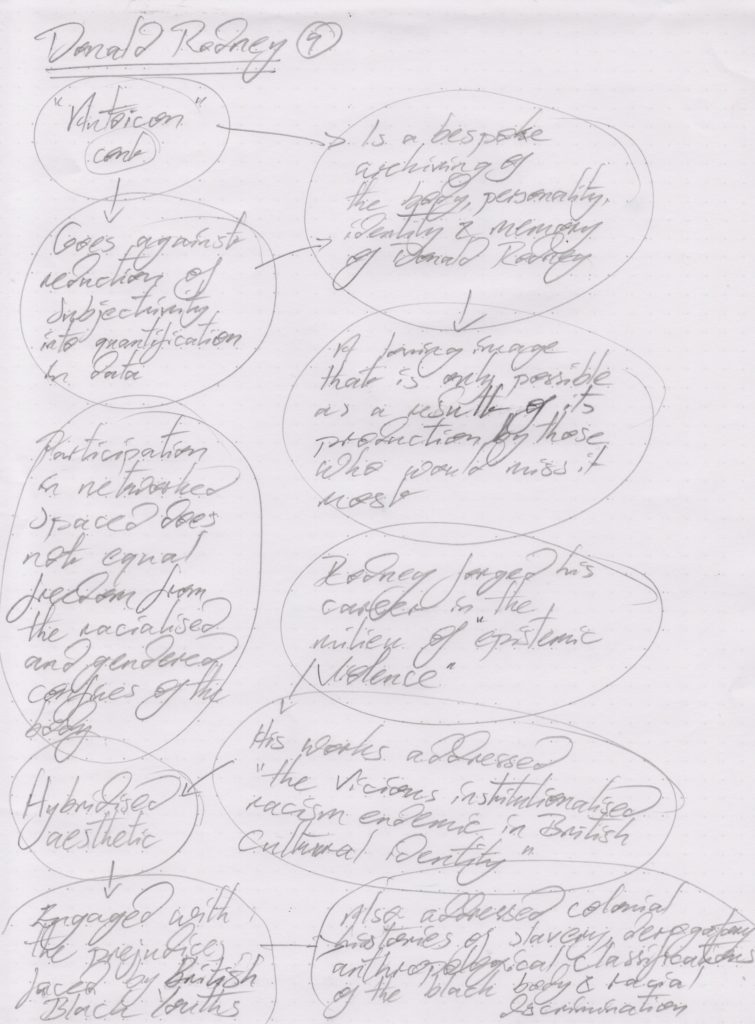

But it is Rodney’s ‘Autoicon’ project, completed posthumously in 2000, that offers the most powerful echo of the artist’s corporeal presence. An interactive digital installation, that responds to user input, assembled a ‘virtual body fashioned from Rodney’s biomedical ‘data trail of information…the endowment of this ‘avatar’ with ‘Rodney’s memories and experiences, fleeting images from the past…and the inclusion of an artificial intelligence [to] allow visitors to enter into conversation and discuss the development of new ideas and projects, that can evolved and be maintained in the organic Rodney’s absence.’ (Birkett, 2023)

Fig.4. Autoicon (2000)

By deliberately creating work that would outlive his physical body, Rodney enacted a form of self-care that outlived his physical body. His practice became an act of care for his future memory and continued presence in cultural discourse. What might have been forgotten – his daily lived experience of illness, the medical interventions – is instead preserved and elevated to the realm of artistic significance. Through his work Rodney ensures that his body, in both its presence and absence, continues to communicate with power and poignancy.

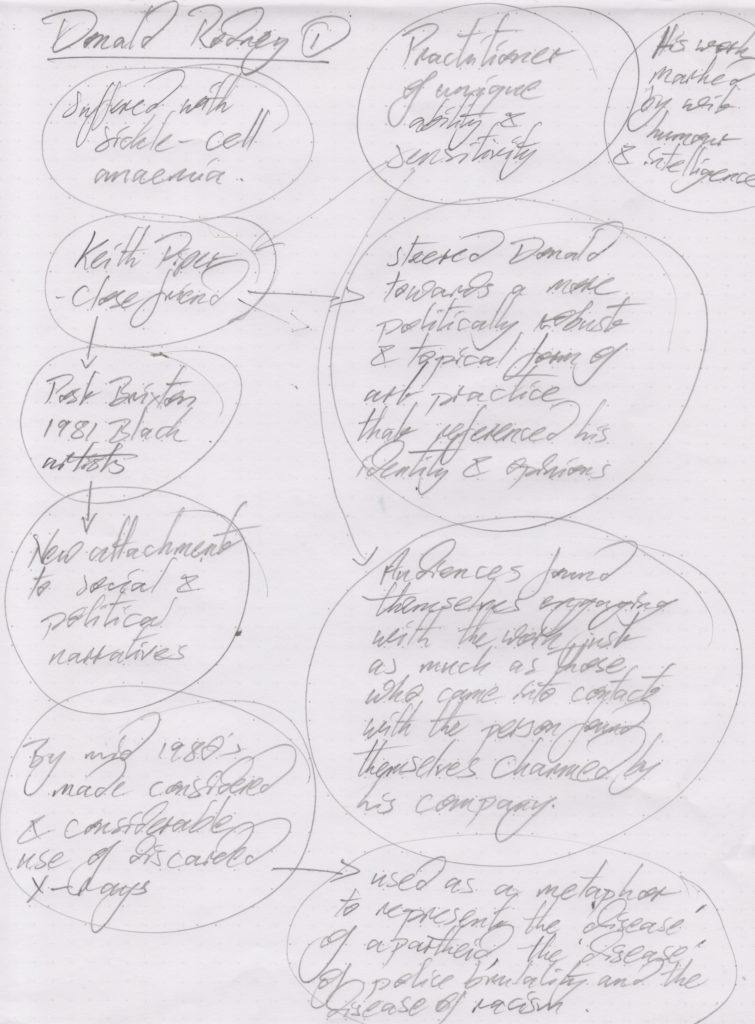

Research Notes

List of References

Conway, J (1997) Psalms At: https://i-dat.org/psalms/ (Accessed 23/03/25)

Birkett, R (2023) ‘Donald Rodney: Autoicon’ In: Donald Rodney, A Reader London: Whitechapel Gallery pp. 159-173

Bibliography

Barson, T (2002) In the House of My Father At: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/rodney-in-the-house-of-my-father-p78529 (Accessed 23/03/25)

Birkett, R (2023) ‘Donald Rodney: Autoicon’ In: Donald Rodney, A Reader London: Whitechapel Gallery pp. 159-173

Chambers, E (1999) Biography: Donald G Rodney At: https://web.archive.org/web/20081107053857/http://www.iniva.org/autoicon/DR/bio.htm (Accessed 23/03/25)

Correia, A (2019) Self-Portraiture and Representations of Blackness in the Work of DONALD RODNEY In: Journal of Contemporary African Art (45) pp. 74-86

Cox, G., Phillips, M., (2000) ‘Donald Rodney – Autoicon. The Death of an Artist‘ In: Landa, K., and Molina, A. (eds), EMERGENT FUTURES, Art, Interactivity and New Media. Valencia: Institució Alfons el Magnànim

Nimarkoh, V., (2003) ‘Image of Pain: Physicality in the Art of Donald Rodney’ In: Donald Rodney, A Reader London: Whitechapel Gallery pp. 38-49

Weller, S (2020) Review: AUTOICON: The digital body – a work by Donald Rodney At: https://iniva.org/review-autoicon-the-digital-body-a-work-by-donald-rodney/ (Accessed 23/03/25)

Weller, S (2019) Acknowledging the body in online art At: https://iniva.org/acknowledging-the-body-in-online-art/ (Accessed 23/03/25)

List of Illustrations

Fig.1. Phillips, M (2018) Psalms (Atlantic Project, Plymouth 28 September – 21 October 2018) [Online Video] At: https://youtu.be/VB5Ii-tXipE?si=D9EVe18ZdoKbn5tP (Accessed 23/03/25)

Fig.2. Phillips, M (2016) Psalms is the Autonomous Wheelchair constructed by Guido Bugmann for Donald Rodney’s “Nine Night in Eldorado” at the South London Gallery, 1997 [Online Video] At: https://youtu.be/Mp7uhsMYfn8?si=gIYbp0Wi25w7d7xh (Accessed 23/03/25)

Fig.3. Ronald, D., Cox, G., Phillips, M., Nimarkoh, V., Hylton, R., Piper, K (2000) Autoicon [Photograph of Screenshot] At: https://i-dat.org/autoicon/ (Accessed 23/03/25)

Fig.4. Ronald, D., Cox, G., Phillips, M., Nimarkoh, V., Hylton, R., Piper, K (2000) Autoicon [Photograph of Screenshot] At: https://i-dat.org/autoicon/ (Accessed 23/03/25)