Curation as Activism

From the Latin ‘curatus’ the past participle of ‘curare’

Meaning – To take care of. To provide for. To worry or care about. To heal, to cure.

But in the art world, what exactly is being cared for? What is exactly is being provided for?

For too long, ‘care’ or curation in cultural institutions around the world, particularly in the West, equated to choosing and organising items to reinforce the dominant societal ideology – white patriarchy – and the privilege & power it engenders.

“In the West, greatness has been defined since antiquity as white, Western, privileged, and, above all, male”

(Nochlin, 2015 cited in Reilly, 2018: 17)

This ‘mode’ of curation, if you like, has ‘written’ a history and created an Institution of art that discriminates and ‘others’ artists that don’t conform – women, artists of colour, LGBTQIA2S+, outsider artists: the art world still privileges the work of western white men: “Discrimination against these artists invades every aspect of the art world, from gallery representation, auction price-differentials and press coverage to inclusion in permanent collections and solo exhibition programs” (Reilly, 2018).

But as societies across the world become more aware of the different forms of structural discrimination at play, the more that the previously ‘othered’ voices begin to challenge the hegemony of white patriarchy. And it is artists and curators that are in the vanguard of this challenge, wielding the axe of discourse to tear down the oppressive structures that have long dictated how the establishment should be.

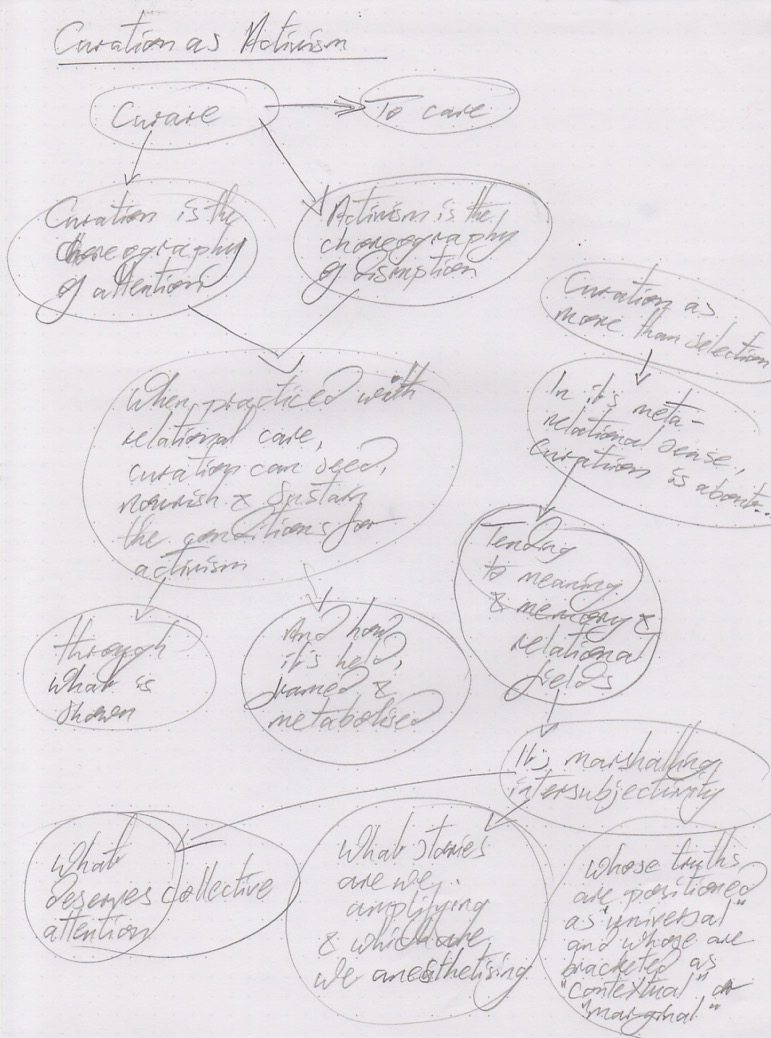

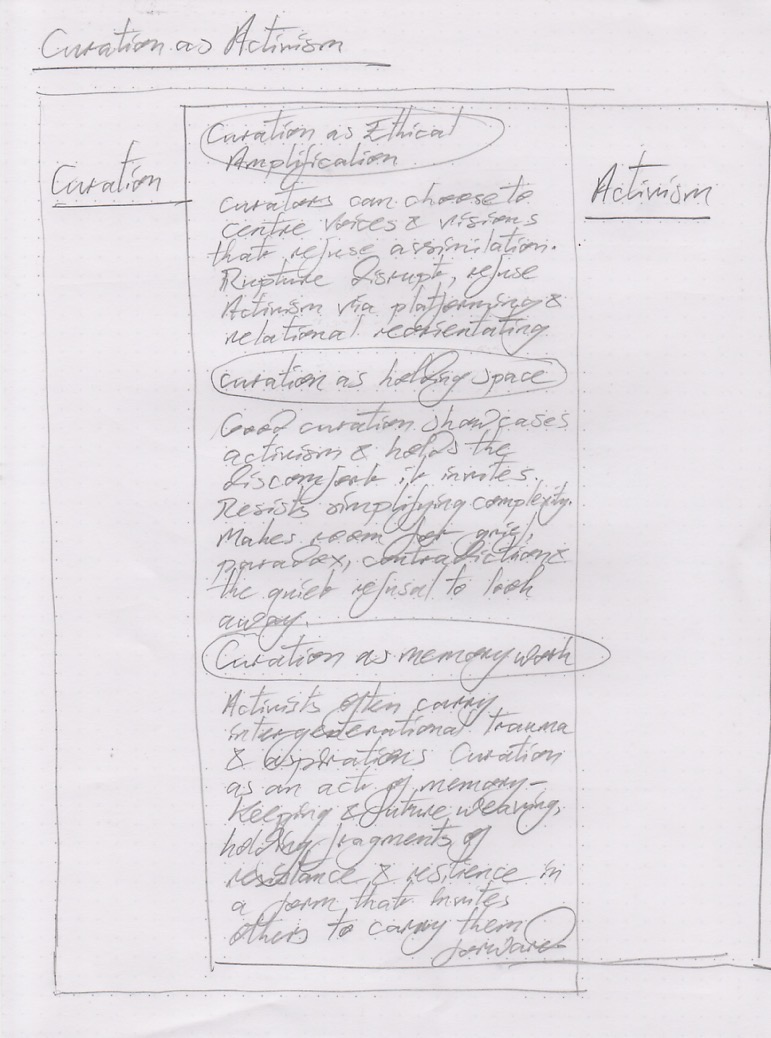

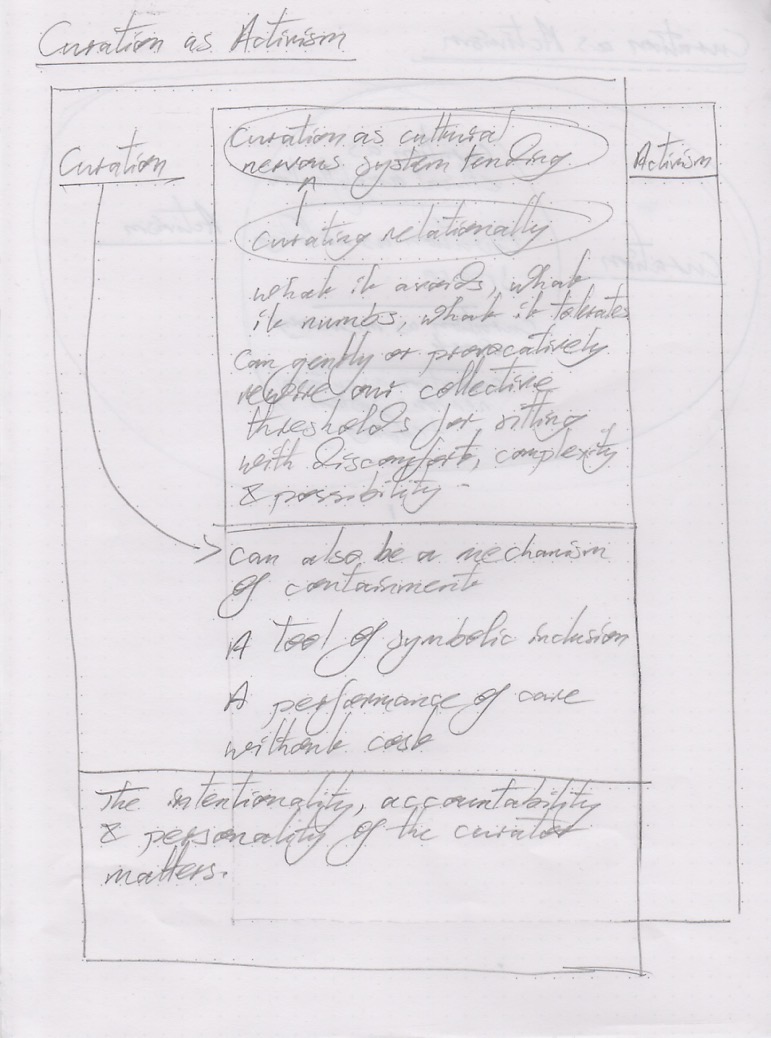

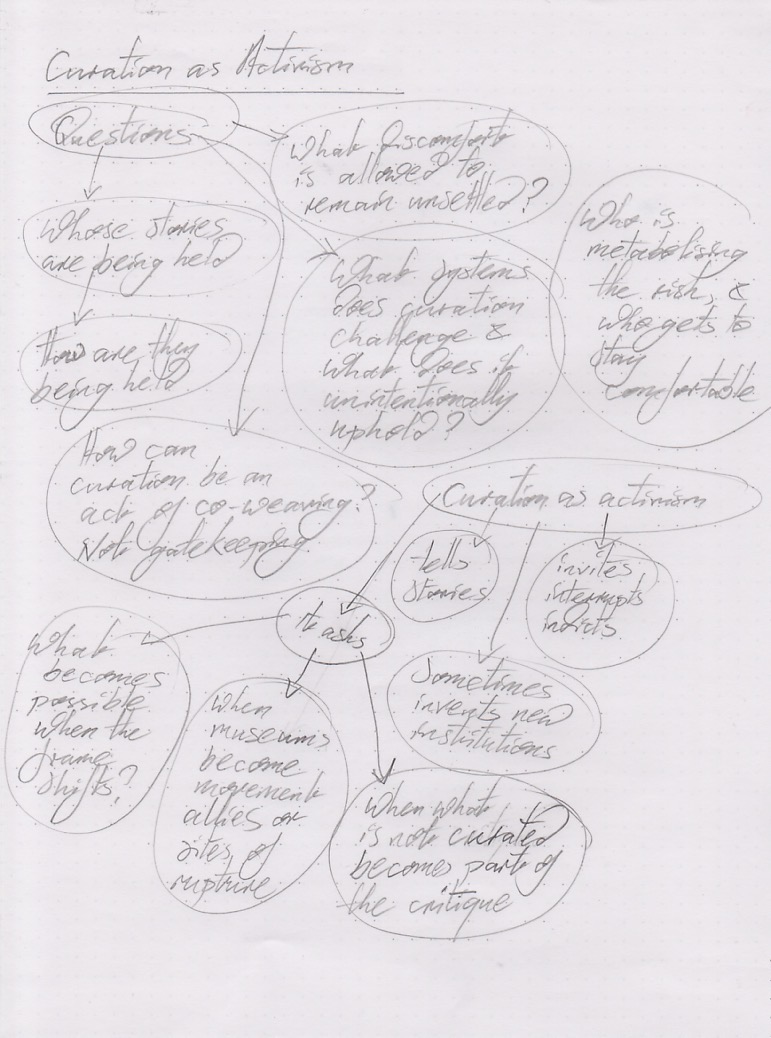

Curators are now practicing their art, for curation is an art, with relational care, to seed and nourish the conditions for a more inclusive discourse about the world. They see curation as more than selection, they see it in its meta-relational sense, as tending to – caring for – meaning, memory and relational fields. They understand it as marshalling the intersubjectivity that exists between artist, work, display space and audience. They are asking “what deserves collective attention”? What stories are we amplifying and what are we anesthetising? How can we challenge those truths that have been positioned as universal and how can we empower the voices that have previously been bracketed as contextual or marginal?”

“Alternative activities are born out of social and contemporary demands, addressing gaps that existing institutions fail to acknowledge or accommodate. In a sense, they are not created by grand political narratives, but instead emerge from the necessity to rescue small stories that have been neglected” (Imamura, s.d.)

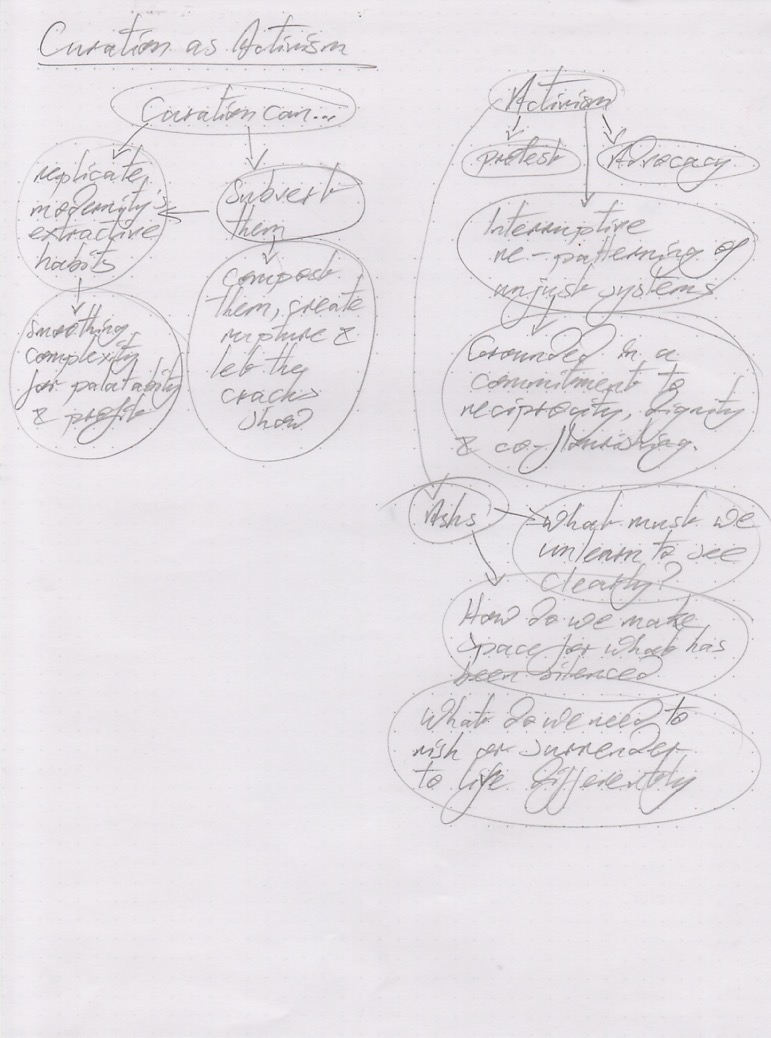

Curation is critiquing the very Institution of Art, presenting the audience with stories that interrupt and subvert the patterns of unjust societal systems. Curators are increasingly feeling an obligation to treat audiences and artists – and the cultural institutions – with respect and dignity, to allow all to flourish:

“Which counter-hegemonic strategies can we employ to ensure that more voices are included, rather than the chosen, elite few. What can we do as arts professionals to offer a more just and fair representation of global artistic production?” (Reilly, 2018).

Curating has begun to recognise that caring involves challenging and disobeying established systems. Curating is translating that recognition into action. And by taking action, curators are becoming activists alongside artists: curators no longer merely choreograph attention, they are also choreographing disruption.

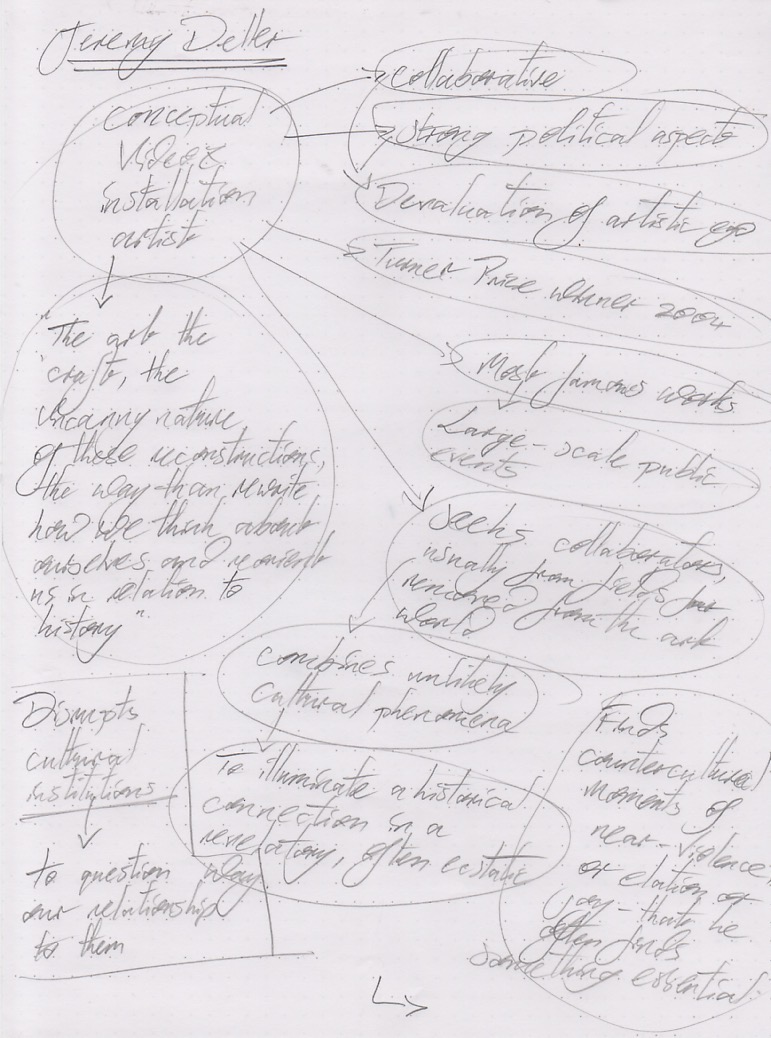

Dimensions of activism are present in the work of Jeremy Deller. 2004’s Turner Prize Winner is best known for his orchestration – or choreography – of large-scale public events. Deller’s work questions and disrupts the idea of the modern British establishment and its institutions, by combining unlikely cultural phenomena to illuminate historical connections in a revelatory, often ecstatic way (Higgins, 2025). Deller’s works are collaborative in process and in execution. He seeks collaborators predominately from fields far removed from the art world, and delegates aspects of the work’s realisation to curators that empathise with his vision. He works within communities, connecting on an almost forensic level with them, extracting the nuances of individuals experiences, before constructing a narrative performance, often national in scale, that heroes the stories of the marginalised, oppressed or forgotten.

Fig.1. Deller’s The Battle of Orgreave (2001).

In 2001’s ‘The Battle of Orgreave’, he recreated the most violent confrontation of the 1984-5 miner’s strike with 1000 volunteers. Through this work he wanted the viewer to see beyond the labour-dispute, to view the confrontation akin to a civil war, where the proletariat (as represented by the miners) had risen up to challenge the establishment order (the police). Deller himself has said that as a public event it had importance as a form of public enquiry, or as an autopsy of an exhumed corpse, to make people angry again (Deller, 2023)

Fig.2. Soldiers at Waterloo station, London. Each represents a real person who died in the Battle of the Somme (2016)

Deller’s ‘We’re Here, Because We’re Here’ subverted the patriarchal tradition of commemorating so-called heroic figures in public statuary, by creating a living “human memorial” (Higgins, 2016) to those that died on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Defiantly unsentimental, 1500 men dressed in WW1 uniforms appeared in public locations across the UK. Unspeaking, they would hand passersby a card bearing the name, rank, regiment, date of and age at the time of their death in 1916. In this work Deller challenges us to reflect on if there has been any change in the structural ideologies at play in society through the lens of an historical event, a human catastrophe caused by the manoeuvrings of an entrenched colonial patriarchy.

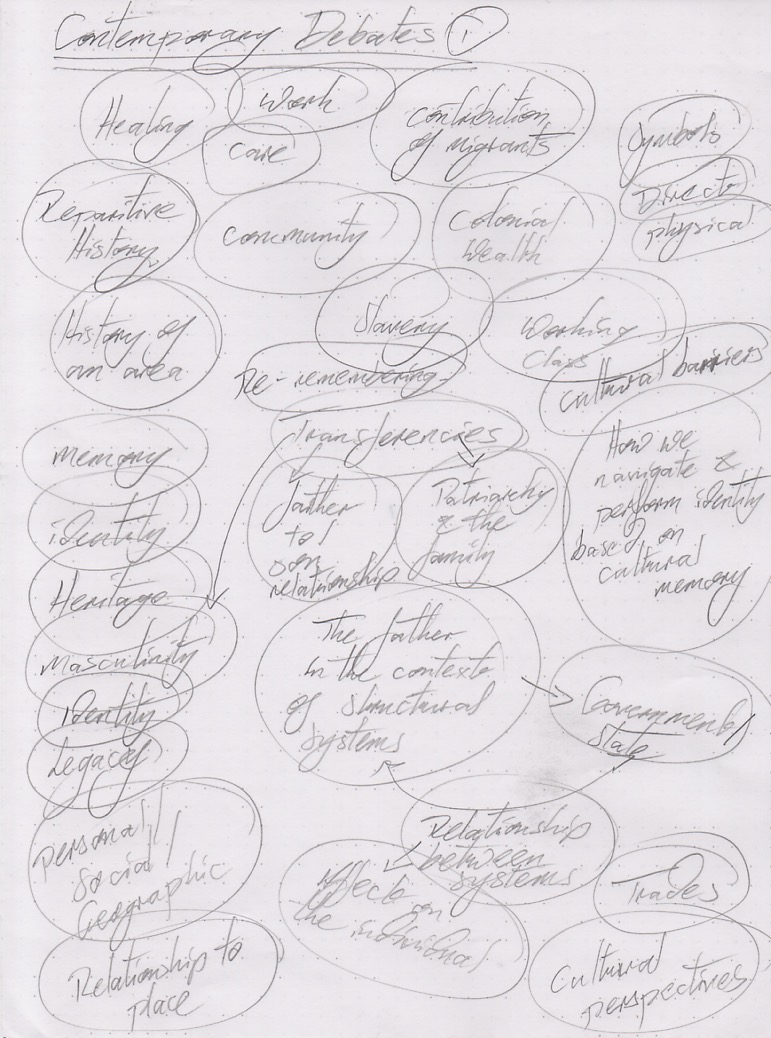

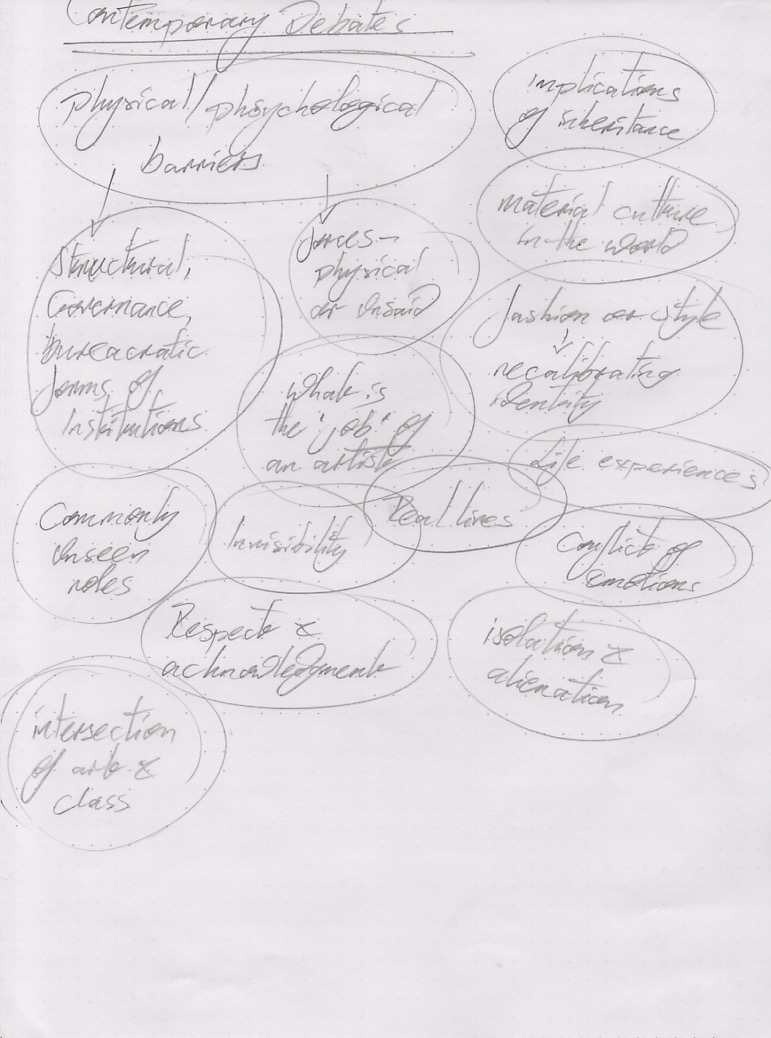

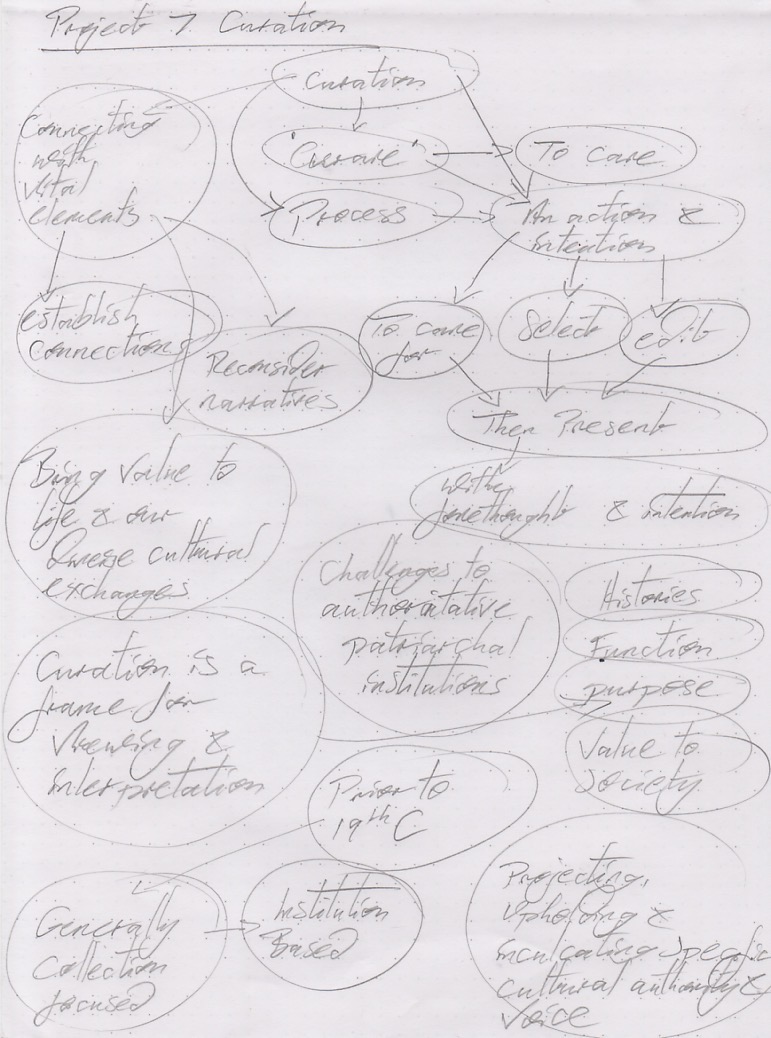

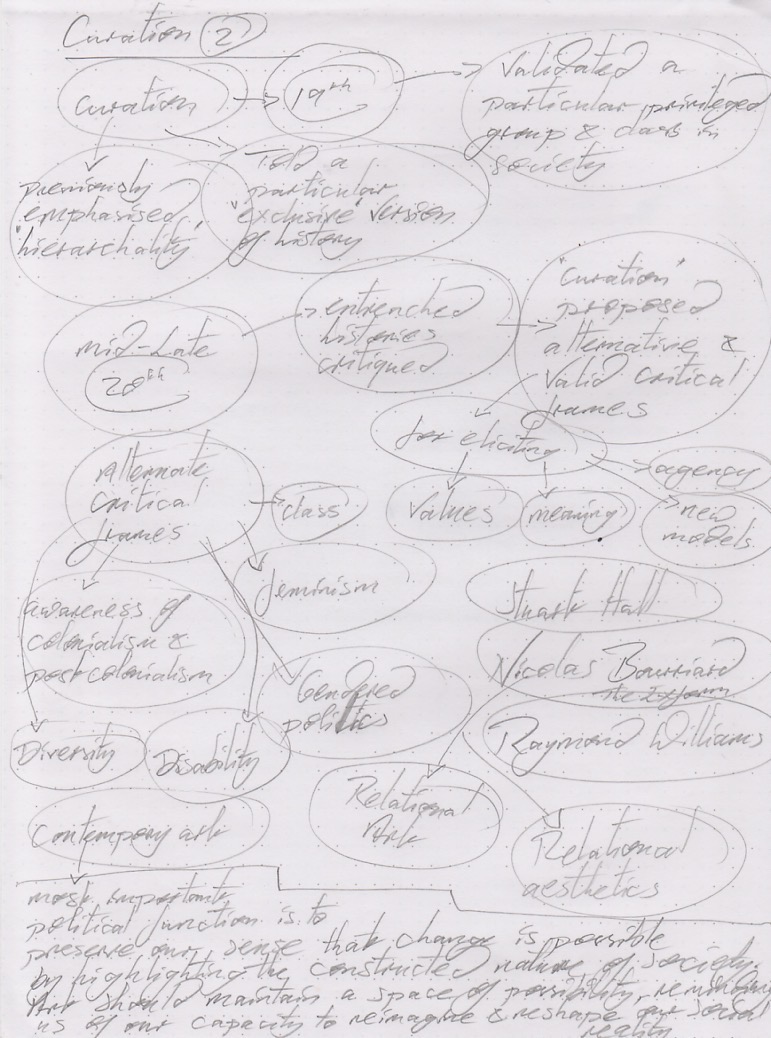

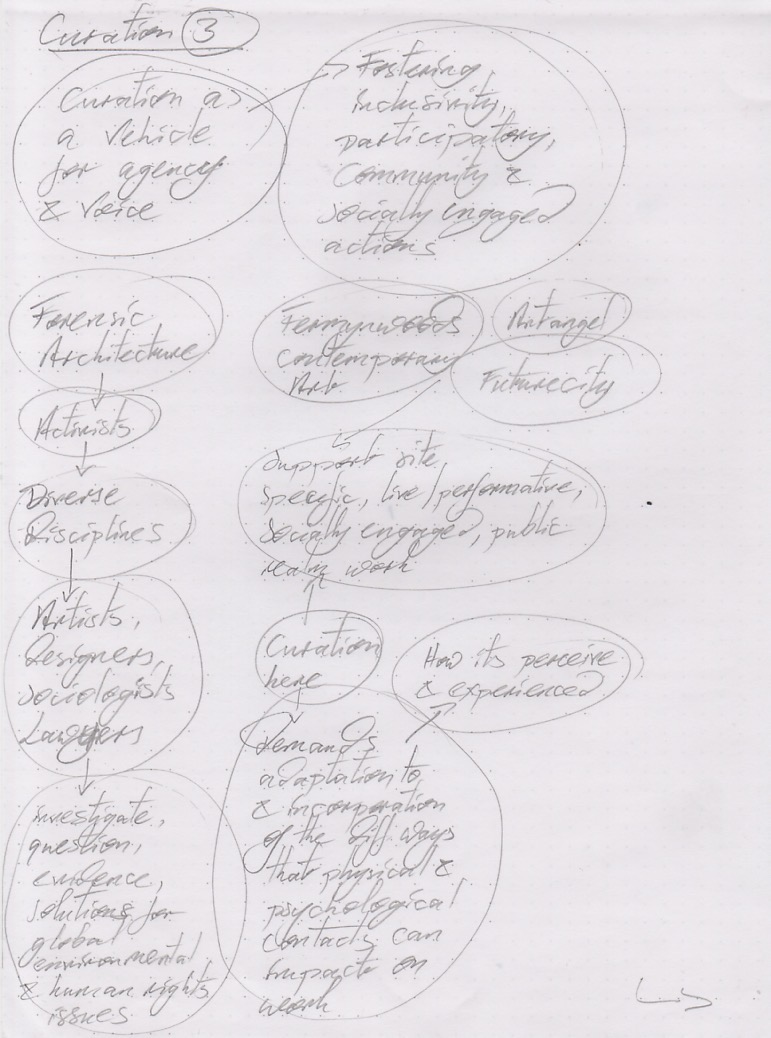

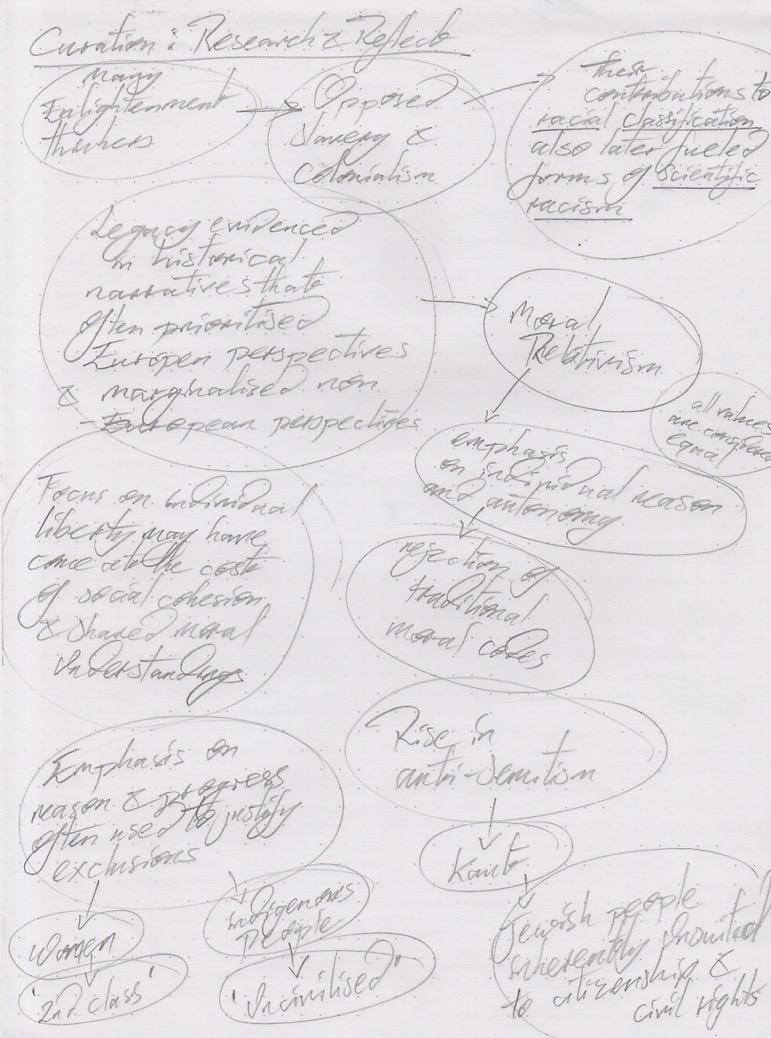

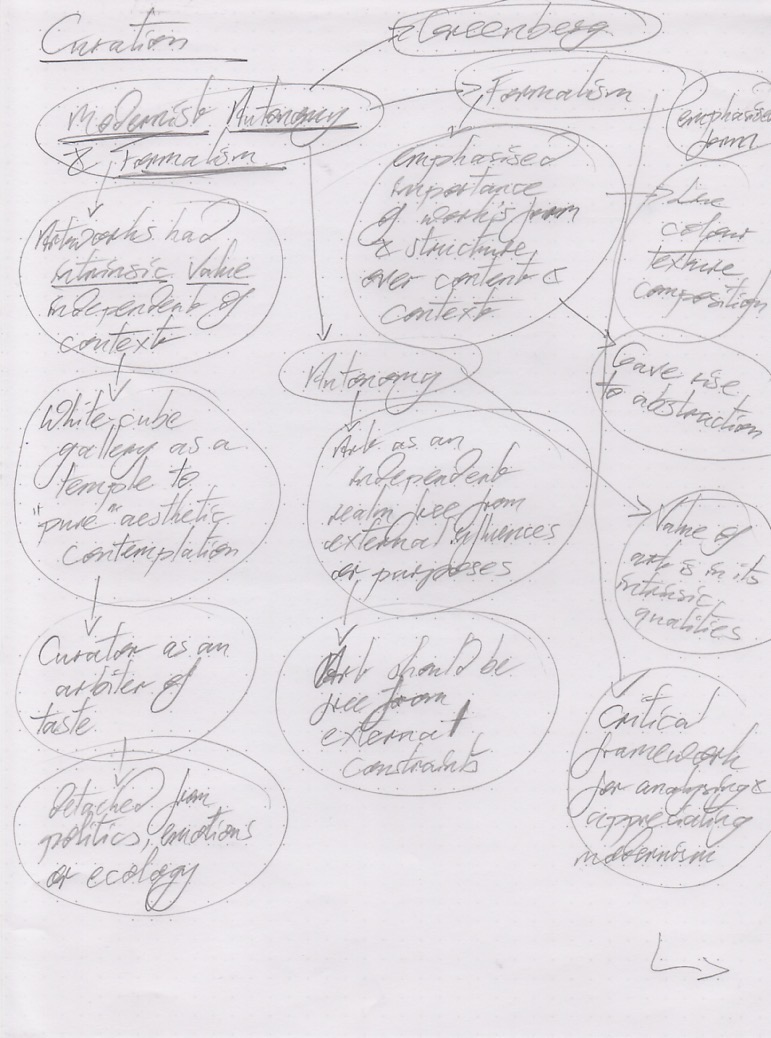

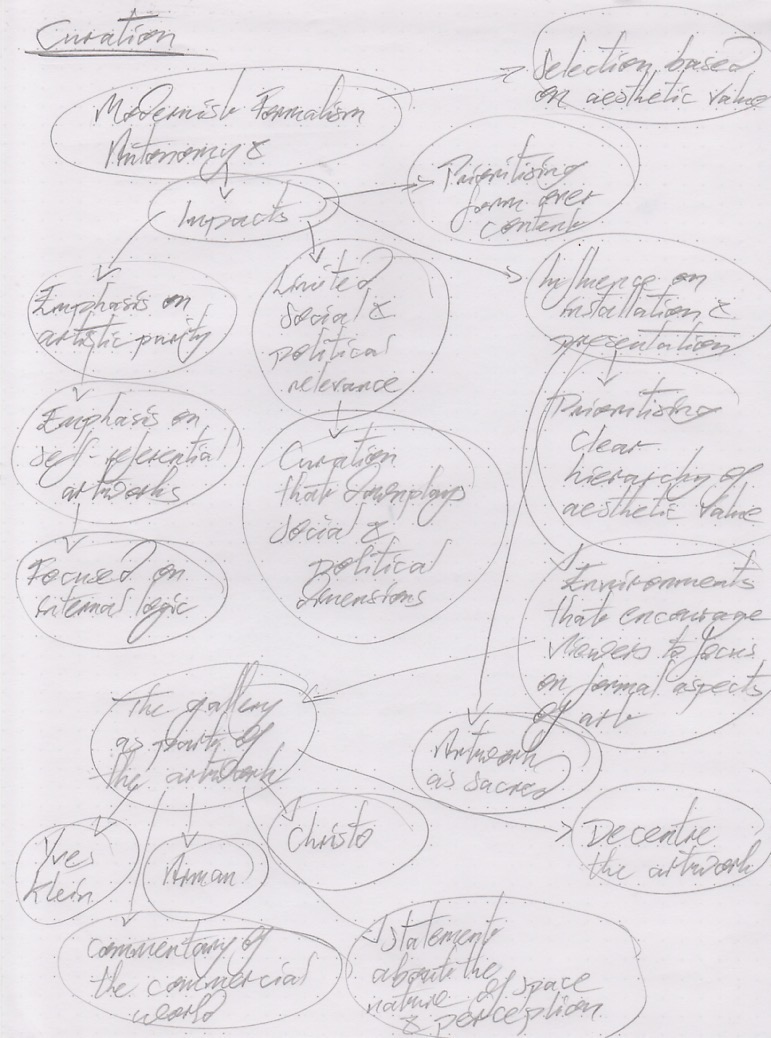

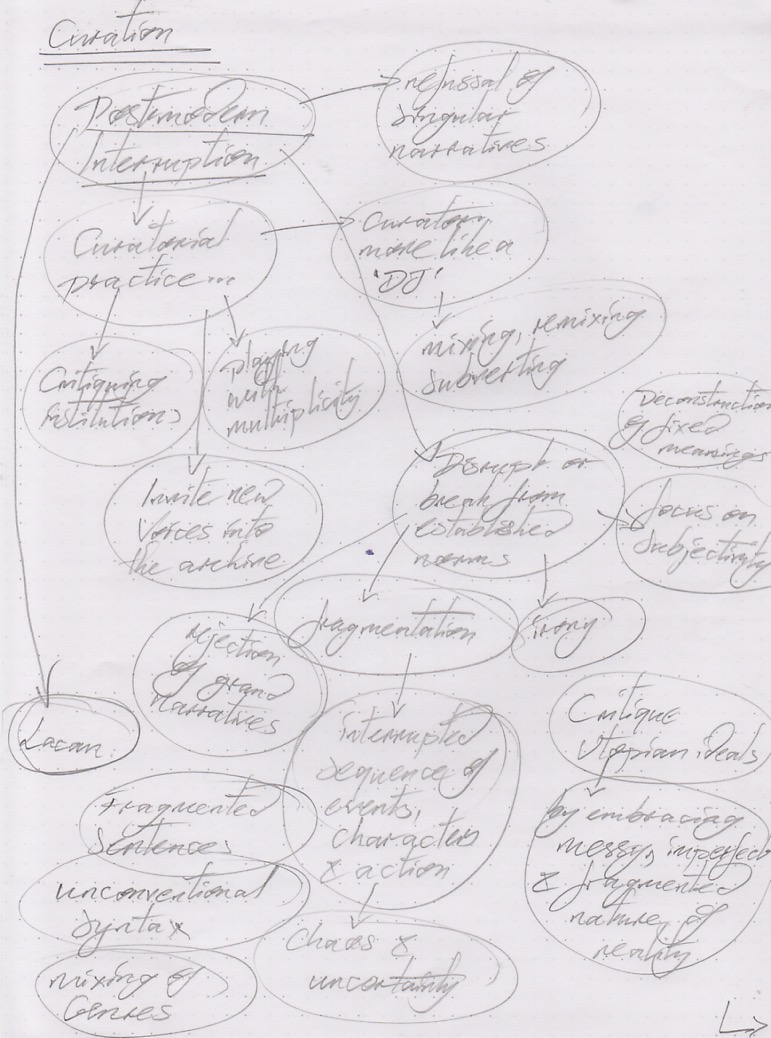

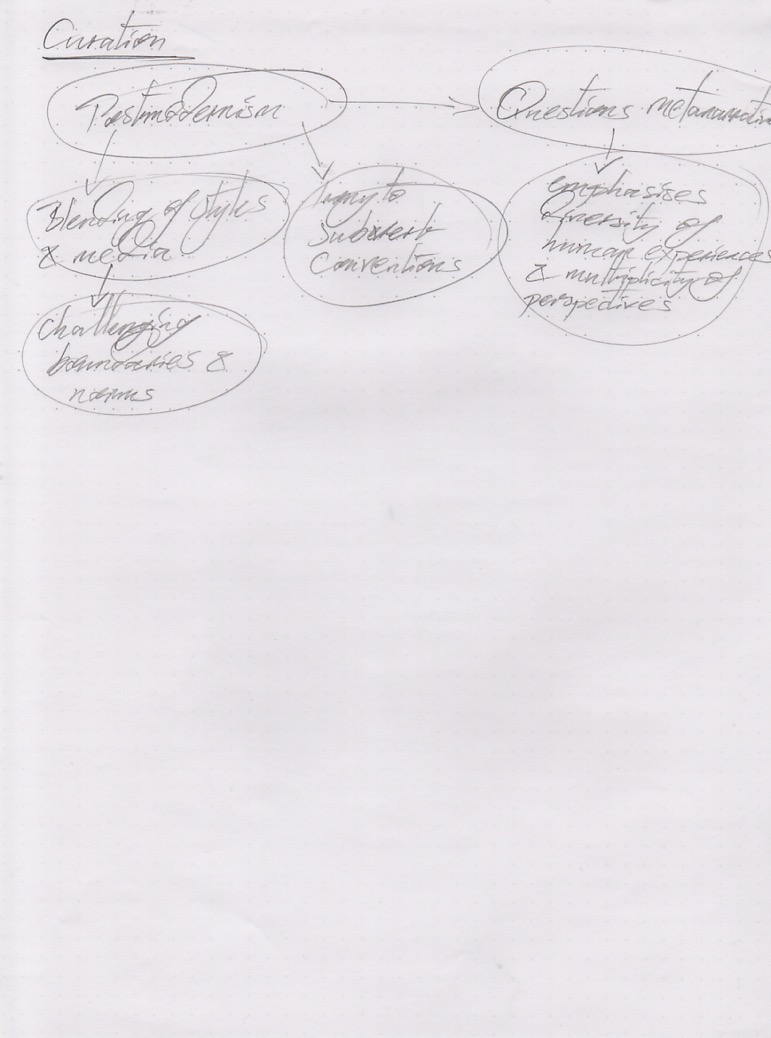

Research Notes

List of References

Deller, J (2023) ‘’It was intended to make people angry again’: Jeremy Deller on restaging the Battle of Orgreave’ In: The Guardian 23/04/23 At: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/apr/23/jeremy-deller-art-is-magic-extract-orgreave-stonehenge-murdochs

Higgins, C (2016) ‘#Wearehere: Somme tribute revealed as Jeremy Deller work’ In: The Guardian 01/07/16 At: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2016/jul/01/wearehere-battle-somme-tribute-acted-out-across-britain

Higgins, C (2025) ‘From acid House to ancient rites: Jeremy Deller’s enormous collaborative, unsellable art’ In: The Guardian 01/04/25 At: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2025/apr/01/acid-house-ancient-rites-jeremy-deller-collaborative-unsellable-art

Imamura, Y (s.d.) New Alternatives-site for Potentiality At: https://curatography.org/zh/sp-8-en/ (Accessed 21/04/25)

Reilly, M (2018) ‘What is Curatorial Activism’ In: Reilly, M. Curatorial Activism London: Thames and Hudson pp.16 – 33

Research

Bibliography

Reilly, M (2018) Curatorial Activism London: Thames and Hudson

List of Images

Fig.1. PA Images/Alamy (2001) Deller’s The Battle of Orgreave [Photograph] At: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2025/apr/01/acid-house-ancient-rites-jeremy-deller-collaborative-unsellable-art (Accessed 21/04/25)

Fig.2. Alicia Canter/The Guardian (2016) Soldiers at Waterloo station, London. Each represents a real person who died in the Battle of the Somme [Photograph] At: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2016/jul/01/wearehere-battle-somme-tribute-acted-out-across-britain (Accessed 21/04/25)