“Slavs and Tatars is a faction of polemics and intimacies devoted to an area east of the Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China known as Eurasia. The Collective’s practice is based on three activities: exhibitions, books and lecture performances”

(Slavs and Tatars: 2025)

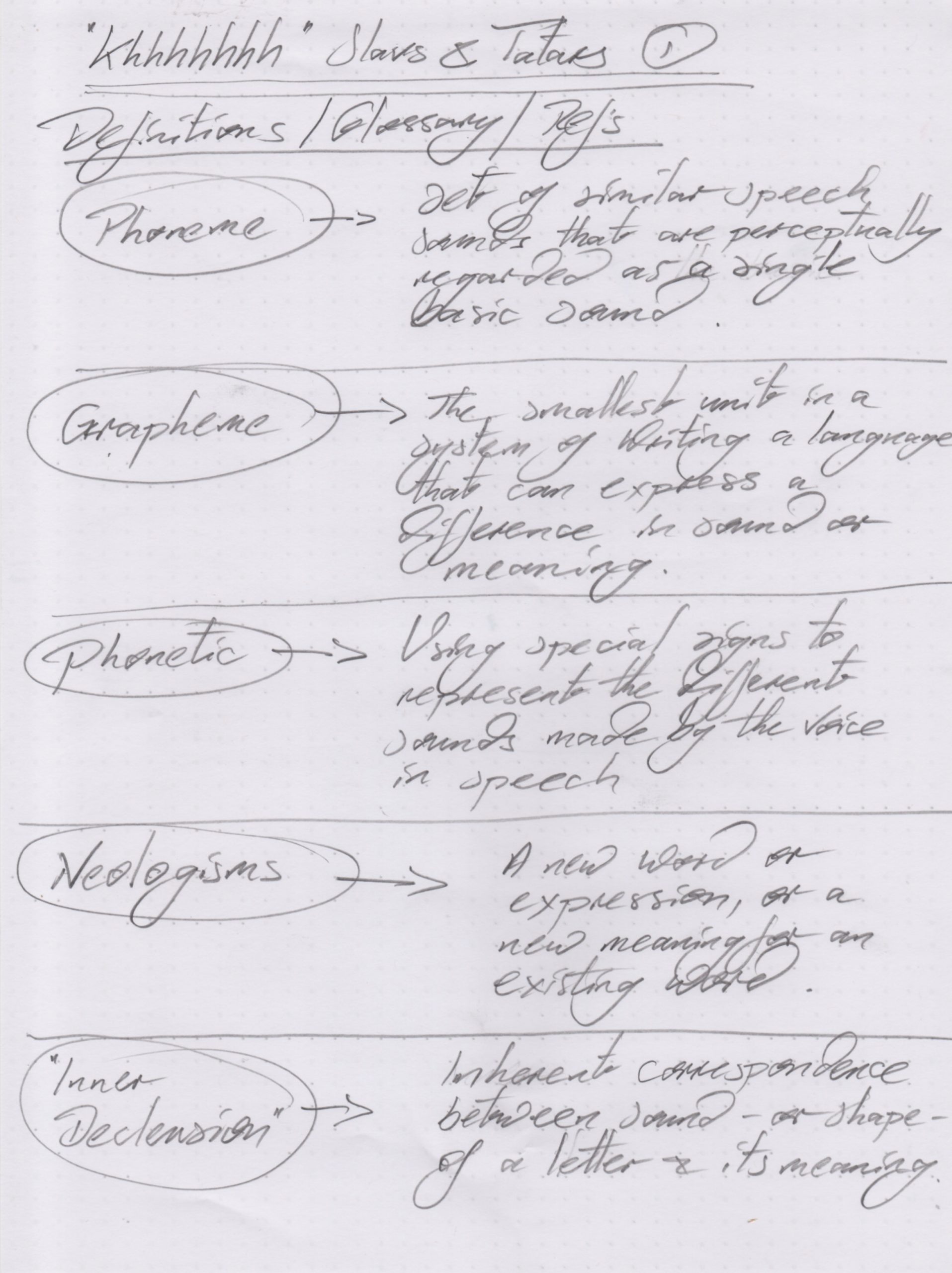

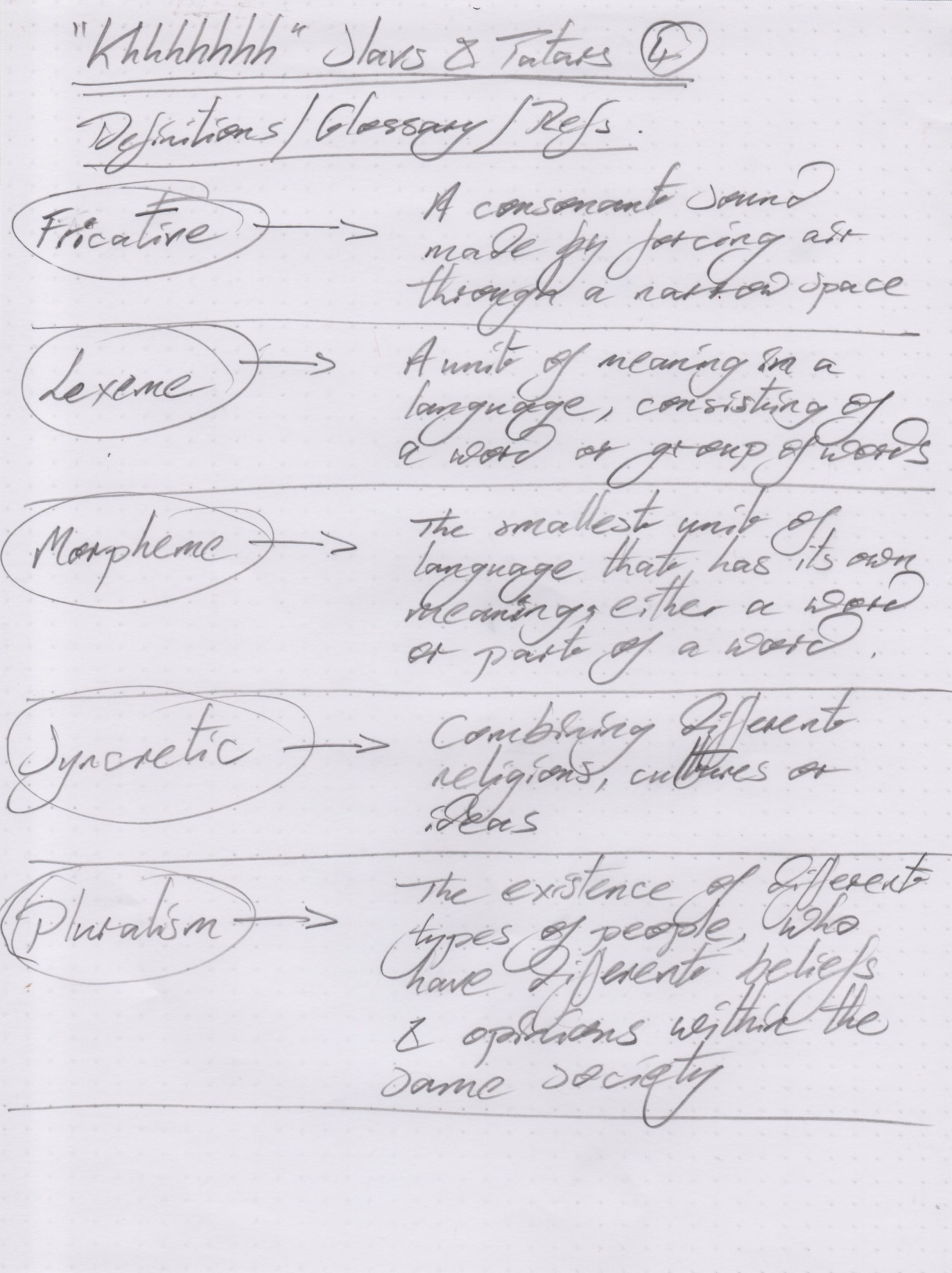

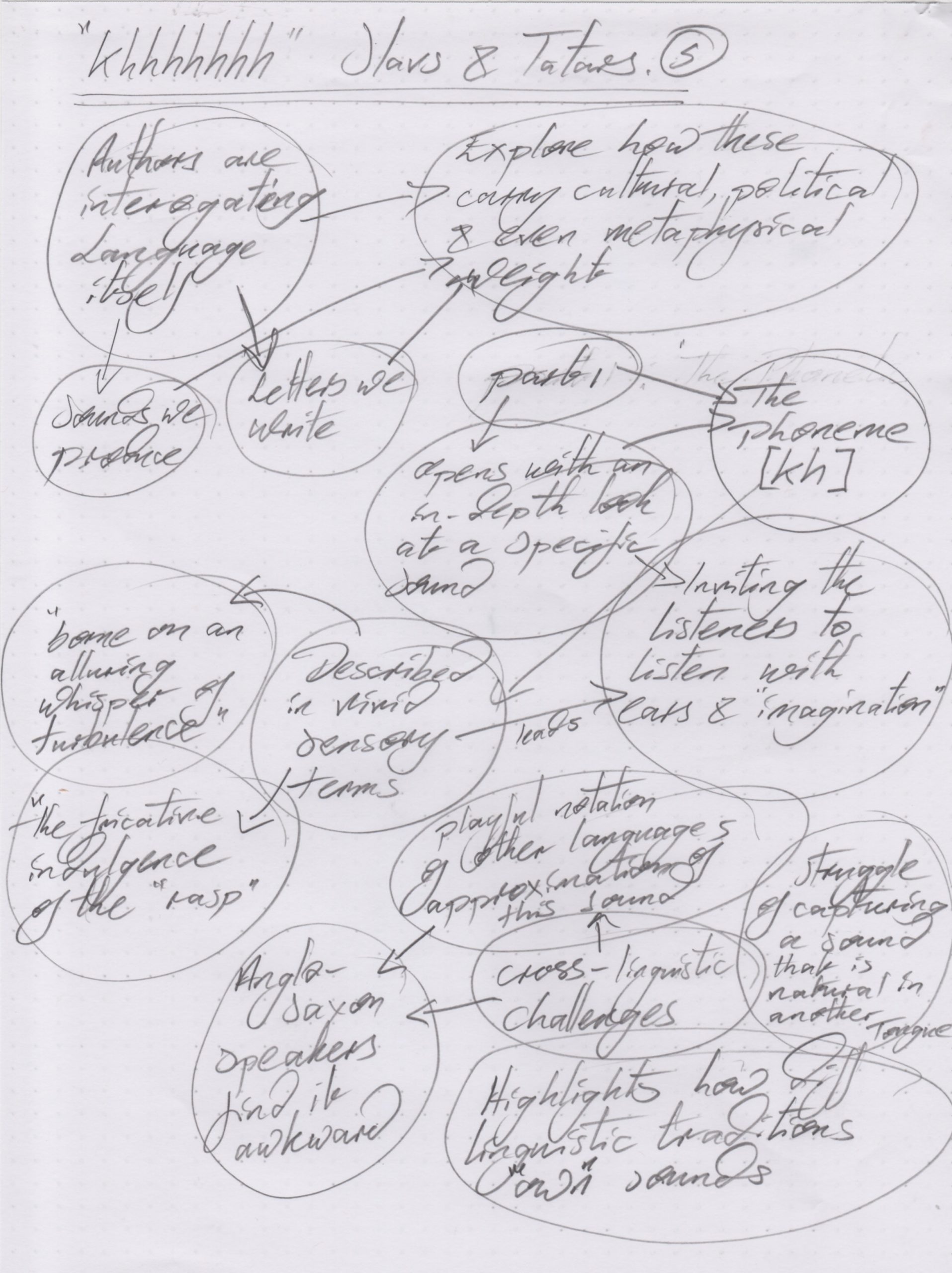

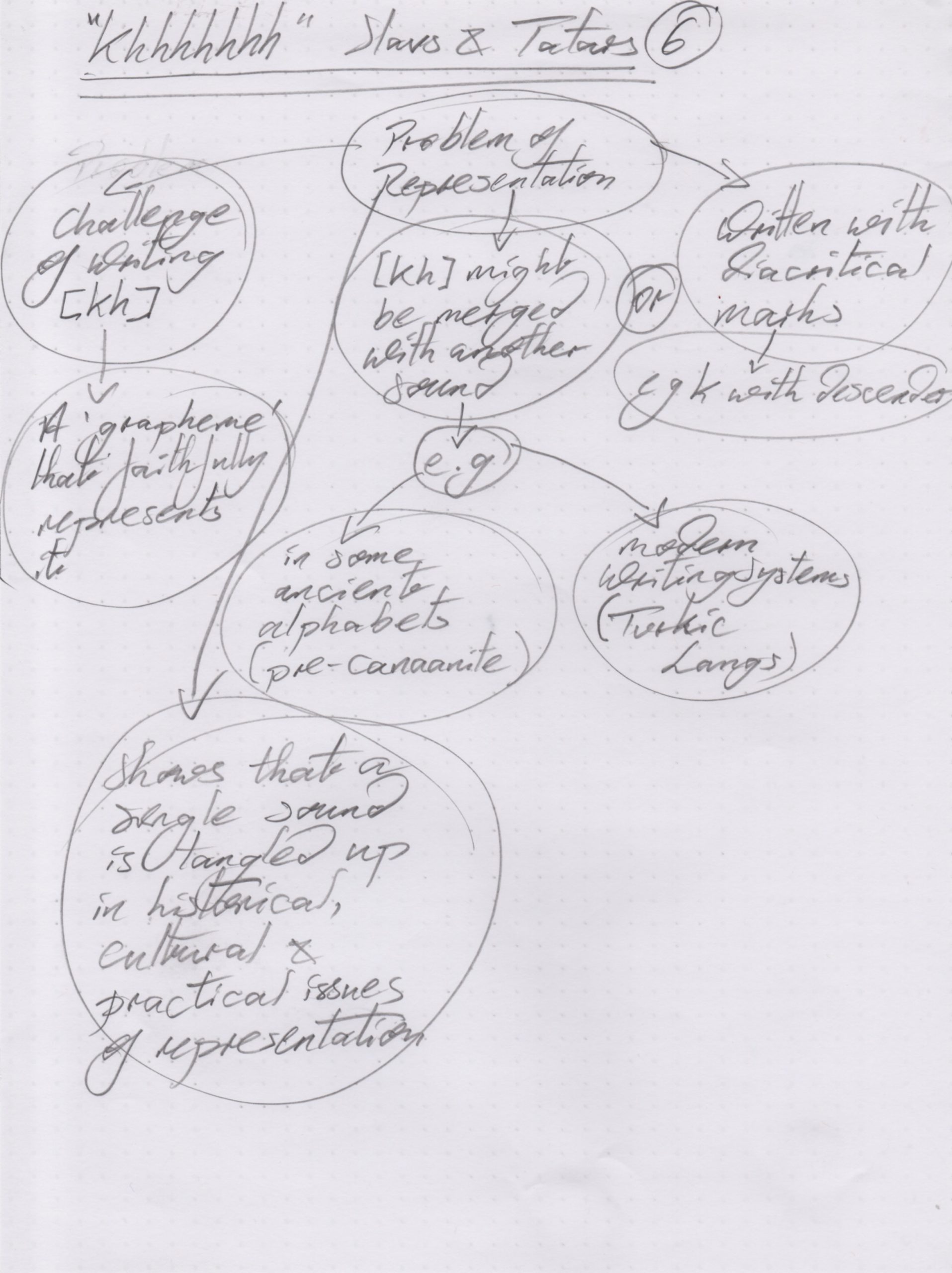

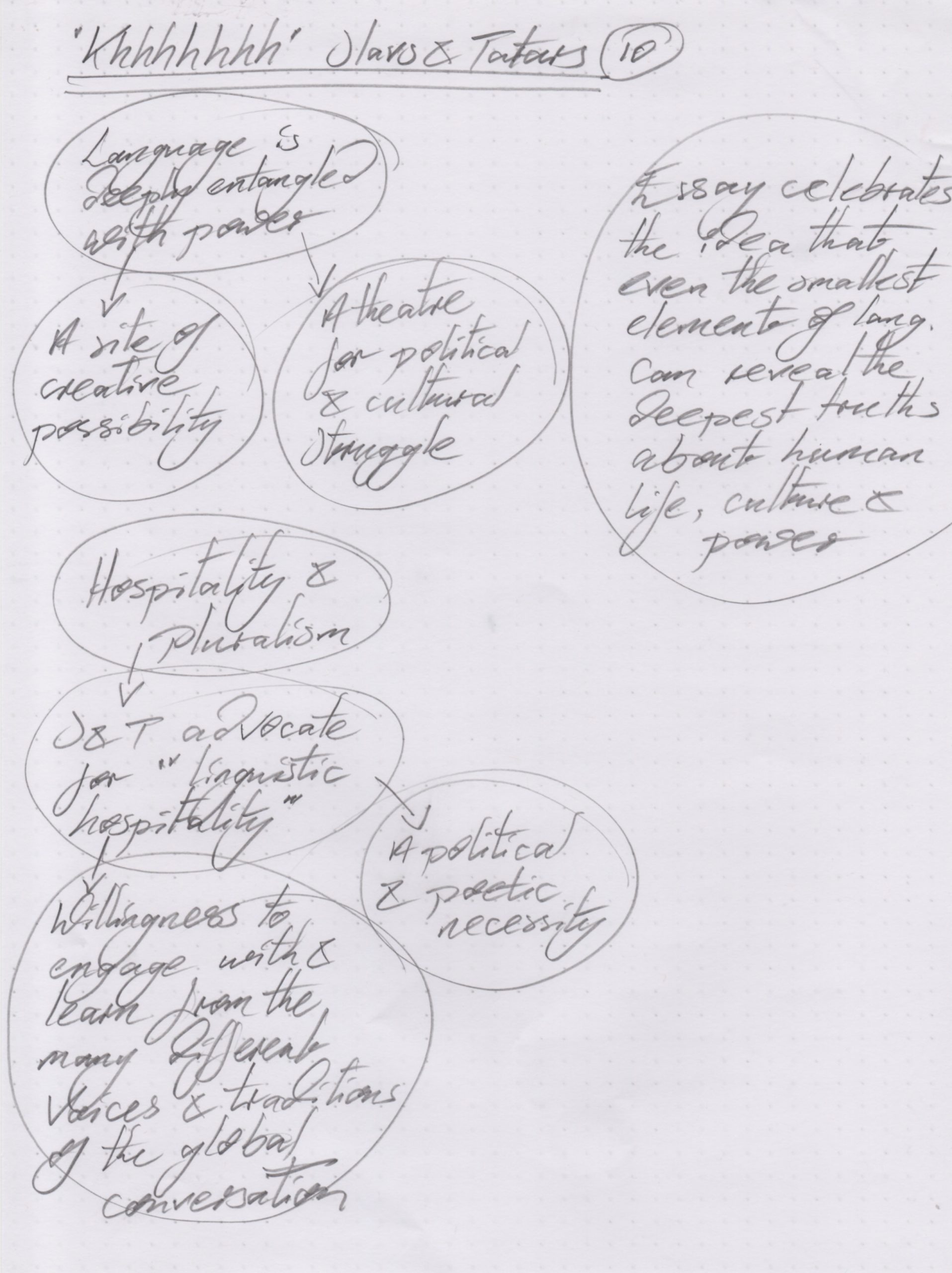

Slavs and Tatars open their essay with a playful, almost obsessive focus on a single phoneme—[kh]—that carries with it a host of physical, linguistic, and cultural resonances. They evoke sensory and bodily experiences—air constriction, a rasp at the back of the throat—to illustrate how language is as much felt as it is heard. In doing so, they draw on familiar cultural touchstones, citing examples from German, Spanish, and Scots, and they contrast these with the awkwardness experienced by Anglo-Saxon speakers. This vivid, experiential approach creates a tangible link between abstract phonetic concepts and personal, embodied memory.

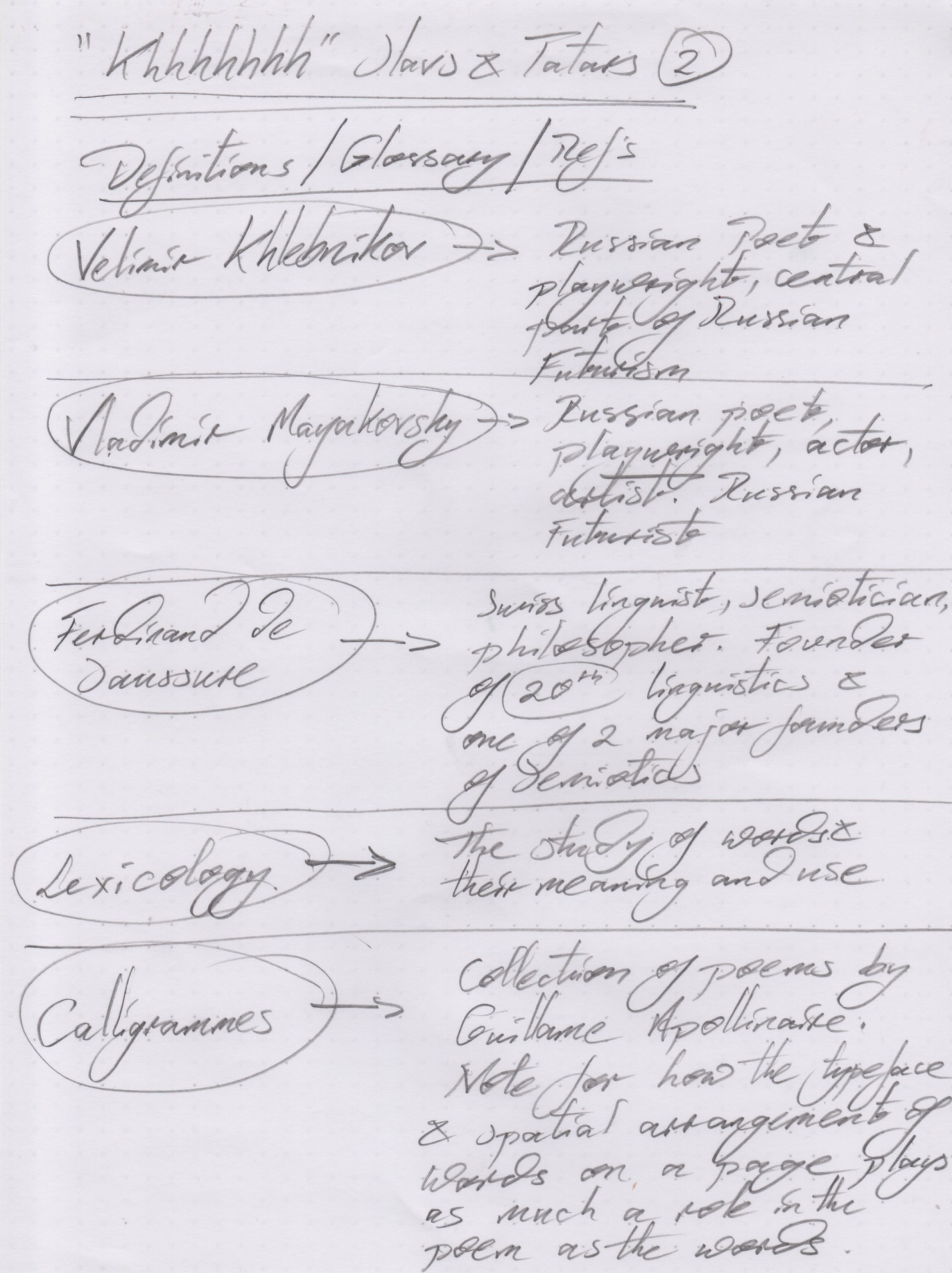

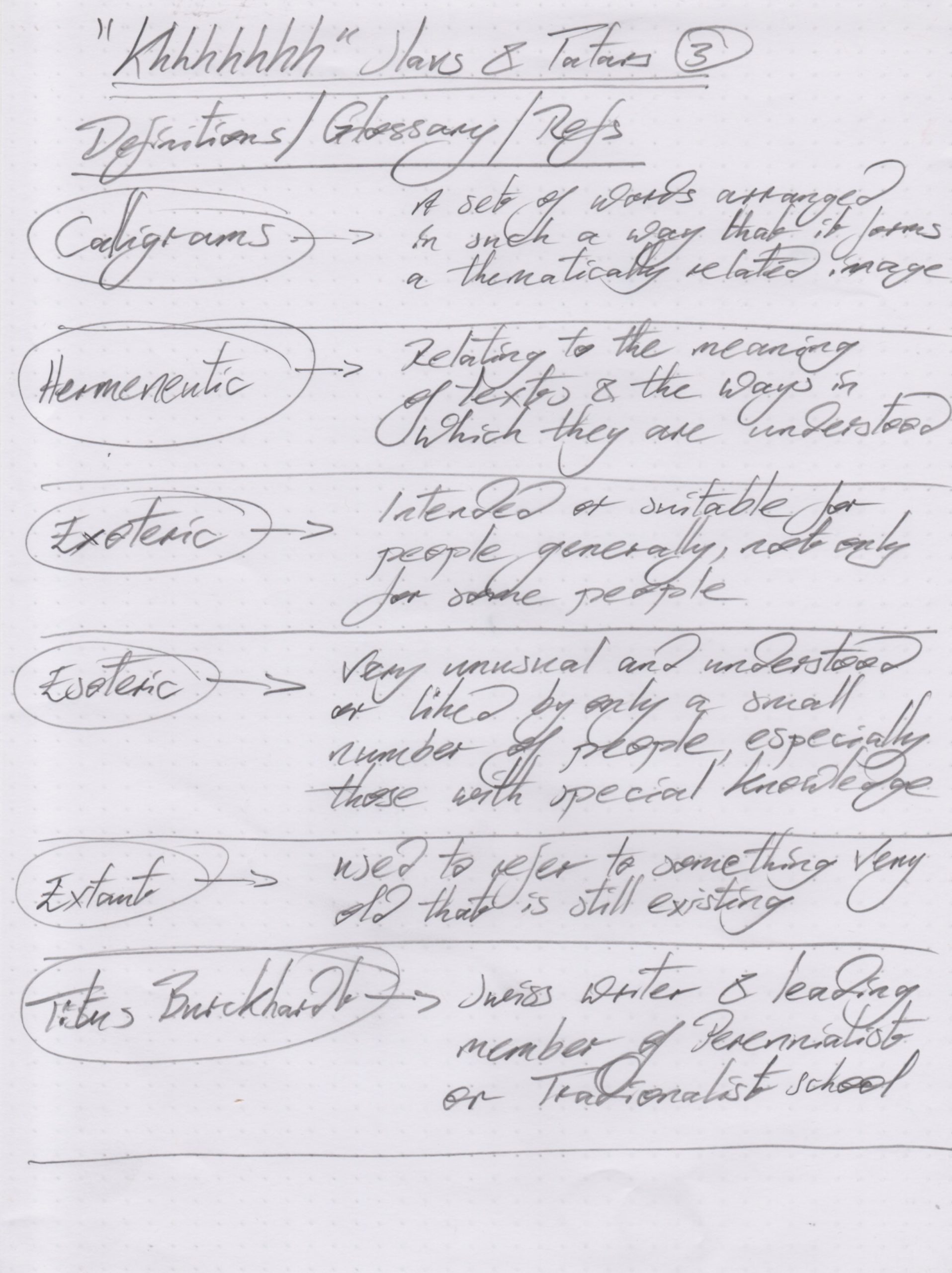

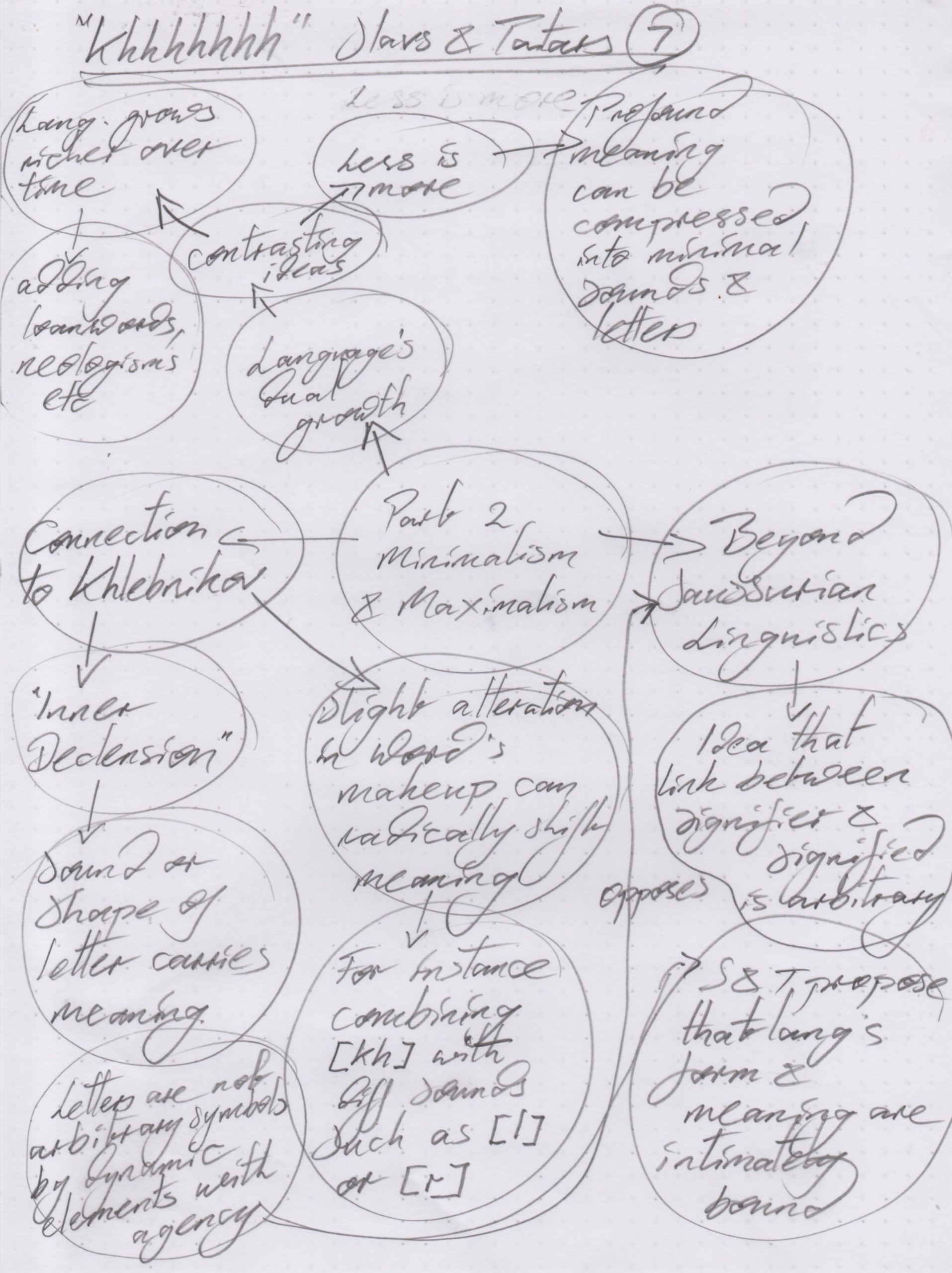

The authors then shift to a meditation on the “less is more” maxim in language, challenging the assumption that linguistic evolution is solely an additive process. By invoking Velimir Khlebnikov’s radical ideas about the “inner declension” of words, they remind us that the intrinsic shape and sound of letters can transform meaning profoundly. This discussion situates Khlebnikov among a host of early twentieth-century innovators—like Steiner and Apollinaire—whose experiments with language sought to uncover hidden, almost mystical correspondences between form and meaning, thereby questioning the Saussurian notion of arbitrariness in language.

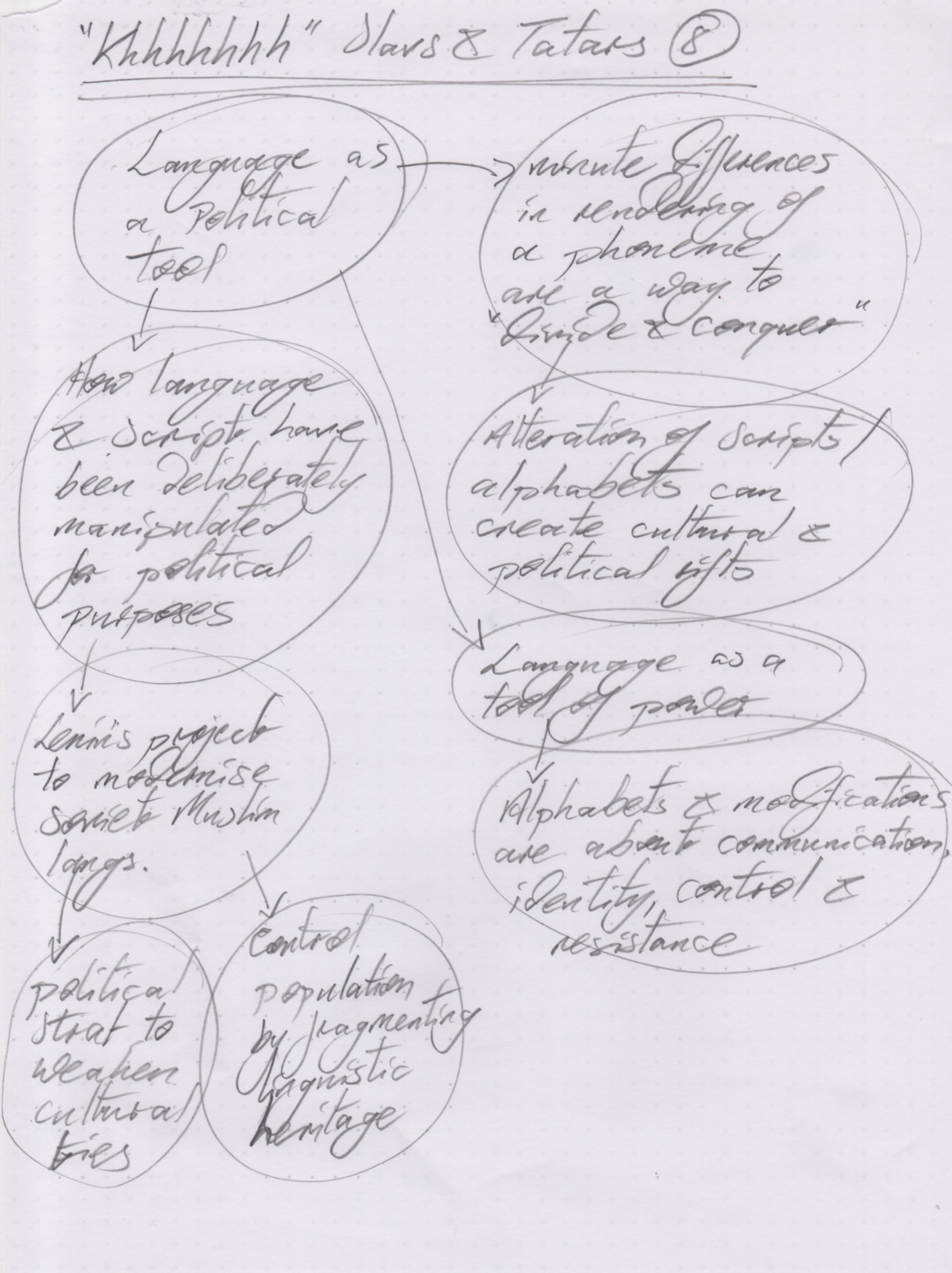

A further layer of the essay addresses the political and historical dimensions of language. Drawing on episodes from Soviet history, the authors recount Lenin’s and later Stalin’s efforts to reshape language through script reforms among Soviet Muslims. This manipulation of alphabets—switching from Arabic to Latin to Cyrillic—serves as a stark reminder that language is a political tool, used to divide and control. The detailed comparisons in graphemic representations among Turkic languages evoke memories of cultural displacement and resistance, underscoring how linguistic shifts mirror broader struggles for identity and power.

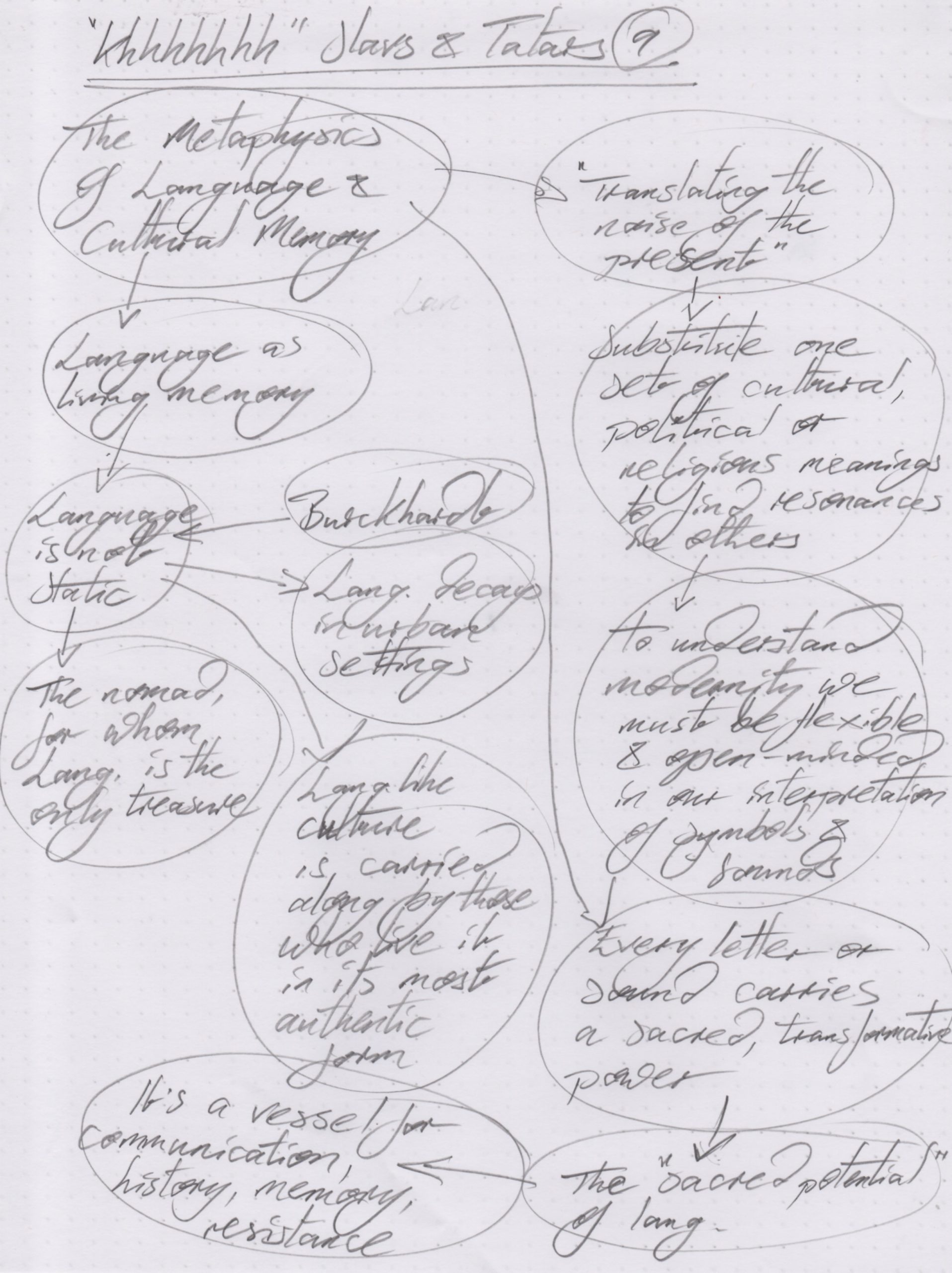

Finally, Slavs and Tatars expand their inquiry to consider language as a living, mutable force that bridges the everyday with the esoteric. They argue that language carries layers of meaning—both visible and hidden—comparable to mystical rituals and personal experiences. Their format, replete with inventive typography and playful digressions, mirrors the fluidity and transformative potential of language itself. This self-reflexive style not only supports their exploration of linguistic history and politics but also questions and ultimately redefines the very tools with which we communicate and remember.

Research Notes

List of References

Slavs and Tatars (2025) About Slavs and Tatars At: https://www.slavsandtatars.com/about (Accessed 08/02/25)

Bibliography

Cambridge Dictionary (2025) Phoneme At: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/phoneme (Accessed 08/02/25)

Cambridge Dictionary (2025) Grapheme At: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/grapheme?q=Grapheme (Accessed 08/02/25)

Cambridge Dictionary (2025) Phonetic At: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/phonetic (Accessed 08/02/25)

Cambridge Dictionary (2025) Neologisms At: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/neologism?q=neologisms (Accessed 08/02/25)

Cambridge Dictionary (2025) Lexicology At: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/lexicology (Accessed 08/02/25)

Cambridge Dictionary (2025) Hermeneutic At: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/hermeneutic (Accessed 08/02/25)

Cambridge Dictionary (2025) Exoteric At: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/exoteric (Accessed 08/02/25)

Cambridge Dictionary (2025) Esoteric At: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/esoteric#google_vignette (Accessed 08/02/25)

Cambridge Dictionary (2025) Extant At: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/extant (Accessed 08/02/25)

Cambridge Dictionary (2025) Fricative At: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/fricative (Accessed 08/02/25)

Cambridge Dictionary (2025) Lexeme At: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/lexeme?q=Lexeme (Accessed 08/02/25)

Cambridge Dictionary (2025) Morpheme At: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/morpheme?q=Morpheme (Accessed 08/02/25)

Cambridge Dictionary (2025) Syncretic At: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/syncretic?q=Syncretic (Accessed 08/02/25)

Cambridge Dictionary (2025) Pluralism At: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/pluralism (Accessed 08/02/25)

Slavs and Tatars (2012) ‘Khhhhhhh’ In: Williamson, S. (ed) Documents of Contemporary Art: Translation. London: Whitechapel Gallery. pp. 39-43

Wikipedia (2025) Ferdinand de Saussure At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinand_de_Saussure (Accessed 08/02/25)

Wikipedia (2025) Calligrammes At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calligrammes (Accessed 08/02/25)

Wikipedia (2024) Velimir Khlebnikov At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Velimir_Khlebnikov (Accessed 08/02/25)

Wikipedia (2025) Vladimir Mayakovsky At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vladimir_Mayakovsky (Accessed 08/02/25)

Wikipedia (2024) Calligrams At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calligram (Accessed 08/02/25)

Wikipedia (2024) Titus Burckhardt At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Titus_Burckhardt (Accessed 08/02/25)