Fig.1. Yellow Heech (2012)

Parviz Tanavoli – ‘Heech’ sculptures

- Heech is a return to the very essence of Iranian culture, both physically and symbolically, the concept of oneness of a human being and God, the pinnacle of the Sufi path

- “contemporary artists have tended to articulate the relationship between tradition and the Muslim experiences of the modem by appealing to the contemporary social and political complexities of the cultural zones that they occupy” (Babaie, 2011: 133)

- “Braiding together densely patterned texts and motifs familiar from popular forms of piety and superstition with traditional representational strategies of Persian painting and metalwork….many of those reformers opened the gates toward a modernity that resonated with an identity grounded in local popular idiom” (Babaie, 2011: 138)

- “In turn, Iranian diaspora artists … activate a host of perceptual and practical referents of that sort of collective memory through visual strategies that retool the localized language into a modernist and postmodern idiom that expands, furthermore, their embedded meanings into a psychocultural space of tension and resolution between tradition and modernity” (Babaie, 2011: 138)

- “these artists (both from Iran and its diasporas) join the graphic artists of the revolutionary phase in Iran in utilizing familiar motifs and visual strategies as if they were hypertext, generating intersecting mental, textual, visual, and performative meanings legible to the culturally trained eye irrespective of the recipient’s proclivities for either high or low art.” (Babaie, 2011: 139)

- Tanavoli turns ‘nothing’ into ‘something’

- Nothing acquires a form, becomes a figure, has a shape, can have a body, emotion

- In some forms of Islamic Art, the representation of sentient beings is frowned upon (aniconism), a result of the prohibition of idolatry, and the belief that the creation of living beings is God’s prerogative. Calligraphy has assumed the mantle of representing the figures of worship.

- Heech consists of three letters, starting with the Arabic ha which represents God for the Sufis, and for Islamic numerologists as the letter of guidance

- “Tanavoli ‘s Heech uses the three letters of the alphabet-“he,” “ye,” and “che”-to create the word “heech,” which translates as emptiness or nothingness. This nothingness can be seen as the mystical stage of being emptied out and reaching a level of nothingness where the material world is no longer emphasized, and the spiritual takes its place at the center of the arena. Reaching this state of nothingness is a long process; it doesn’t come overnight. This journey and state of nothingness can best be seen in poetry: in The Mathnawi of Rumi (Maulana Jalalu’ d-din Rumi, otherwise known as Molavi) or in Attar’s Conference of the Birds” (Ebrahimian, 2003: 20-22)

- Tanavoli transforms the Farsi word into the pictorial space through sculpture by giving it form, shape and mass. And by giving it form, mass, shape, Heech becomes a representation of a sentient body, one that can be ‘worshipped’ (in the artistic sense) as is inherent nature is calligraphic

- Calligraphy is a signifier of Islamic culture

- In Islamic Art studies, “primacy is given to ornament and calligraphy in all the arts, and formal and technical beauty are privileged at the expense of an examination of the meaning of the work or its complex sociocultural referents, other than vaguely defined mystical sentiments attributed to these artists” (Babaie, 2011:139)

- Tanavoli is (possibly) reflecting on this tension between this focus on the ornamental and calligraphic (the heech & nothing), and the meanings that he assigns to each piece

- His work has been described as ‘Poetry in Bronze’ (Highet, 2015)

- Co-founder of the Saqqakhaneh group, a neo traditional movement which sought to reintegrate and reinterpret traditions such as calligraphy and classical poetry from traditional Iranian Heritage

- Often referred to as the ‘School of Spiritual Pop Art’

- Kamran Diba makes a fascinating comment: ‘There is a parallel between Saqqakhaneh and Pop Art, if we simplify Pop Art as an art movement which looks at the symbols and tools of a mass consumer society as a relevant and interesting cultural force. Saqqakhaneh looked at the inner beliefs and popular symbols that were part of the religion and culture of Iran, and perhaps, consumed in the same ways as industrial products in the West’. (Diba, quoted in Highet, 2015)

- “The Saqqa-khaneh movement in the sixties tried to find and establish a “national” or “Iranian” school of painting. Kamran Diba noted that “what made this movement revolutionary was the modernistic [approach to] tradition and sense of freedom from the bonds of past cultural cliches. If the very notion of the avant-garde can be seen as a function of the discourse of originality, the actual practice of vanguard art tends to reveal that “originality” is a working assumption that itself emerges from a ground of repetition and recurrence” (Keshmirshekan, 2005: 612-613)

- Tanavoli draws inspiration from Iranian poetry and literature, istoric architectural ornament, local design, vernacular crafts and folklore

- He is drawing on the creative heritage of Iran and applying modernist principles

- Is this a comment on how Iranian culture is wedded to traditional, and struggles with the intrusion of modernity and western values?

- It could also be an ironic comment on the value of his works: ‘nothing’ has become worth something

- Heech, nothing, becomes a vessel for transmitting other ideas, concepts, emotions.

- The posing of the Heeches, their individual situations, their materials of construction, the affordances given by their titles – all provide each Heech a context beyond the literal meaning of ‘nothing’

Fig.2 Heech Lovers (2007)

- Consider ‘Heech Lovers’ from 2007. The sensuous intertwining of the sculptural forms of the two heeches and the casting in rich yellow bronze, evoke the connection between to two deeply emotionally connected people

- Compare to ‘White Heech on a Chair’…..

Fig.3. White Heech on a Chair (2007)

- Here, a contemplative figure, in repose on a high-backed chair, cast in white fibreglass, potentially representing the purity of the thoughts they are having, thoughts of their relationship with God (my reading)

- And further……

Fig.4. Heech in a Cage (2005)

- Beyond ‘nothing being something’, I think that Tanavoli is saying that all of the contexts and situations that his Heech sculptures represent are aspects of mans relationship with their God, whether that be the Islamic, Christian, Buddist perception. Man carries out acts in the name of God because they threaten or underpin a society or an ideology shaped by a specific perception of God

- Considering the foundation letter of Heech – ‘ha’ – is Tanavoli offering us a form of guidance through his sculptures, how to live, how not to live, how to get closer to God

- Is Tanavoli making an ironic statement about the exchange value that the Institute of Art has ascribed to his works?

- The continual repetition of the Heech, albeit in differing contexts, echoes the repetitive use of subject matter in Warhol’s work

Farhad Moshiri’s Use of Language

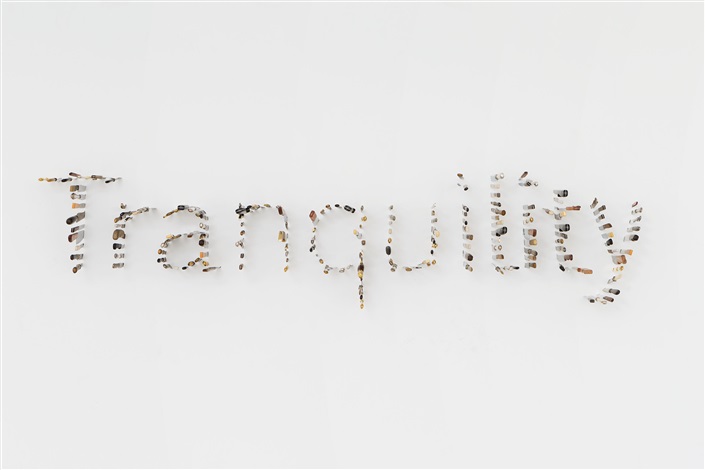

Fig.5. Tranquility (2017)

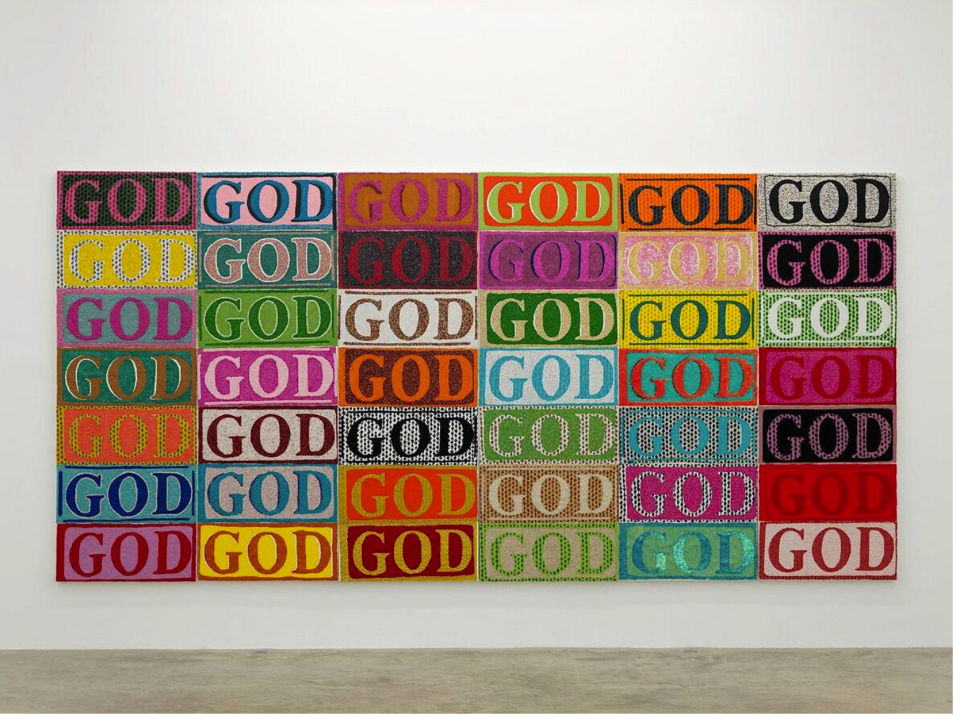

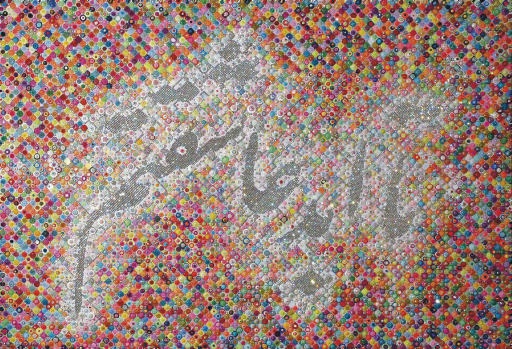

Fig.6. God in Color (2012)

Fig.7. I love you until eternity (2007-2008)

- Moshiri operates in the realms between traditional form and contemporary culture

- He addressed (similar) themes of consumer culture and kitsch aesthetics

- Works play with notions of artifice – Moshiri uses fake diamonds, gold and even fake paint.

- “They seem to indulge in luxury as their primary mode of being. And yet their referents hail from low-brow malls, highway advertisements and inflated Hollywood-inflected ideas about beauty, as well as from Iranian soap operas, advertising culture and cinema. In this way, Moshiri pushes back on the prevailing notion of art as a luxury good and, equally, on art as a site of fantasy. More than ever, all that glitters is not gold.” (Aquirre et al, 2011: 222)

- “What sets his work apart from his contemporaries is the collision of Eastern and Western influences. Iconography from both cultures is combined in such a way that it makes distinctions such as “Eastern” and “Western” seem reductive and even silly” (Walsh, 2017)

- In response to his work being identified as Pop Art: “My art no longer concerns a mere product that is ‘out there’, made by a corporation to feed the masses. What’s more interesting for me is how the masses respond to that and how they twist and shape it, to fit their own interests” (Sagharchi, 2014:80)

- “My work has a lot to do with Iranian culture on the verge of being absurd. It can be described as an all you can eat buffet. There is this famous Iranian wedding anecdote once dinner is served theres a sudden rush for the dinner table. You might get once chance, so you put the appetiser, main dish and dessert on the same plate, just to make sure you get it all. Once you have your kebab and rice, on top of that, you’ll slap on some red Jell-o! I try to reflect that sort of attitude, visually.” (Farhad Moshiri quoted in An Artified World: Interview with Jérôme Sans in R. Janssen, The Third Line, Perrotin & T. Ropac (eds.), Farhad Moshiri, Brussels 2010, p. 18).

- “He draws inspiration from the clash and modernity in 20th century Iran, a world where the paradox reigns. Islamic fundamentalism is juxtaposed against a thriving music and arts scene where television personalities glitter in the public eye whilst a larger poverty lower class struggles to make a living. But this nod to Pop culture, and particularly to the work of Jeff Koons to whom Moshiri is often compared, can also be construed as an appreciation of the Baroque and Mannerist movements, which were marked by ornamental and extravagant excess. As a result of the lax political rules that afforded the Iranians under the Khatami reign, Moshiri has used this lexicon to provide a social commentary on the lavish excesses of Iran in the 2000s.” (Christies.com, 2013)

- Moshiri ‘addressed the flaws of contemporary Iran while toying with its traditional forms, and acknowledged the appeal of the Western world in addition to its limitations.” (The Third Line, s.d.)

- Through the combination of Islamic calligraphy and Western consumerist Tropes, Moshiri is reflecting on the concurrence and clash of the cultures within Iran and the uptake of ‘Westernisation’, despite the political and religious resistance in Iran and traditional Islamic cultures

- His work also highlights the symbiotic relationship of power and religion in Islamic culture: God in Color would be relatively innocuous in a secular context, but would gain a sardonic sheen in an Islamic venue – the commercialisation, the mass marketing of God as a means of maintaining power.

- The work reflects on the contradictions inherent in his home country of Iran where the youth is both rebellious and God-fearing

List of References

Aguirre, P. Azimi, N. Casdan, M (2011) ‘Farhad Moshiri’ in: Vitamin P2: New Perspectives in Painting pp.222-223

Babaie, S (2011) ‘Voice of Authority: Locating the “Modern” in “Islamic” Arts’ In: Getty Research Journal 3 pp.139-149

Christies.com (2013) ‘Farhad Moshiri: Secret Garden’ At: https://www.christies.com/lot/lot-farhad-moshiri-secret-garden-5665804/?#top (Accessed 28/09/24)

Ebrahimain, B (2003) ‘Pictures from a Revolution: The 1979 Iranian Uprising’ In: PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 25(2) pp.19-31

Keshmirishekan, H (2005) ‘Neo-Traditionalism and Modern Iranian Painting:

The Saqqa-khaneb School in the 1960s’ In: Iranian Studies 38 (4) pp: 607-630

Sagharchi, N (2014) ‘(I can’t get no) Satisfaction’ In: Harpers Bazaar Art: Arabia pp:79-83

The Third Line (s.d.) Farhad Moshiri At: https://thethirdline.com/artists/33-farhad-moshiri/ (Accessed 28/09/24)

Walsh, B (2017) An Exhibition by Iranian Artist Farhad Moshiri Might be All We Have Left of Winter in 100 years At: https://www.perrotin.com/en/artists/Farhad_Moshiri/40/press-review/forbes-2017-12-08/2550 (Accessed 28/09/24)

Bibliography

Barati, P (2013) The Key Players in the Iranian Art Market: Parviz Tanavoli At: https://web.archive.org/web/20131105212700/http://www.artomorrow.com/eng/index.asp?page=49&id=206 (Accessed 25/09/24)

Highet, J (2015) Parvaz Tanavoli: The Heech Sculptures At: https://asianartnewspaper.com/parviz-tanavoli-heech-sculptures/#:~:text=Literally%20in%20Farsi%20it%20is,also%20a%20meaning%20behind%20It’. (Accessed 25/09/24)

Cotter, S. Moore, L. Muller, N. (2009) Contemporary Art in the Middle East: Artworld London: Black Dog Publishing

List of Illustrations

Fig.1. Tanavoli, P (2012) Yellow Heech [Bronze] At: https://www.tanavoli.com/works/sculptures/fiberglass/yellow-heech/ (Accessed 25/09/24)

Fig.2. Tanavoli, P (2007) Heech Lovers [Bronze] At: https://www.tanavoli.com/works/sculptures/bronze/heech-lovers/ (Accessed 25/09/24)

Fig.3. Tanavoli, P (2007) White Heech on Chair [Fibreglass] At: https://www.tanavoli.com/works/sculptures/fiberglass/white-heech-and-chair/ (Accessed 25/09/24)

Fig.4. Tanavoli, P (2005) Heech in a Cage [Bronze] At: https://www.tanavoli.com/works/sculptures/bronze/heech-in-the-cage/ (Accessed 25/09/24)

Fig.5. Moshiri, F (2017) Tranquility [Wall based installation with knives] At: https://www.artnet.com/artists/farhad-moshiri/tranquility-La8ddQjJdN6ceTK3d2IM1Q2 (Accessed 28/09/24)

Fig.6. Moshiri, F (2012) God in Color [Hand Embroidery on Canvas] At: https://www.perrotin.com/artists/Farhad_Moshiri/40/god-in-color/23254 (Accessed 28/09/24)

Fig.7 Moshiri, F (2007-2008) I love you until eternity [acrylic, crystals, glitter, pigment and vitrail and oil on canvas laid on board] At: https://www.artnet.com/artists/farhad-moshiri/i-love-you-until-eternity-tLzn2GxAhrnrxe5a2wxLUA2 (Accessed 28/09/24