I have never explored diagrammatic/ evidence-based work as part of my process. I work with it everyday as part of my profession: I have to create blueprints that explain website information architecture, page structures and functionality: I have to visually explain how Users journey through different stages of a purchase journey: I am a contributor to prospective project pitches: and I am responsible for synthesising complex research into insights and actions that are easy to follow for non-technical client audiences. I have never, though, explored the possibilities of diagrammatic artefacts in my personal process.

There are several reasons. My passion for the qualities and possibilities of paint has precluded any consideration of exploring diagrammatic or evidentiary avenues: there are some practices that appear to demand specific materials, and paint doesn’t appear to readily suit diagramming. Then there is my over-riding interest in the figure and the portrait: I have only just begun exploring beyond a representational approach to both, and I haven’t yet understood how those core interests can be used as vessels for discourse on broader social, political, ideological concerns. And there is this question in my mind – “Isn’t all art evidencing something in some way?”. These are reasons based on very narrow perspectives though, and I’m aware that the role of this Unit is to disrupt the comfort zone and explore possibilities to help me establish my position as a contemporary artist.

I did consider ways of reinterpreting work from my professional role, but I couldn’t form a secure rationale for pursuing that direction: there may be something to explore for the future. Then I considered avoiding this exercise altogether as I was becoming angry at how divergent I felt this was from my original expectations of this module. But serendipity showed its hand (as it has many times in the past) in the form of a short video on Instagram of Dr Anita Taylor, judge of the Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing prize talking about the work of the winner of the Working Drawing Prize, from Emma Douglas.

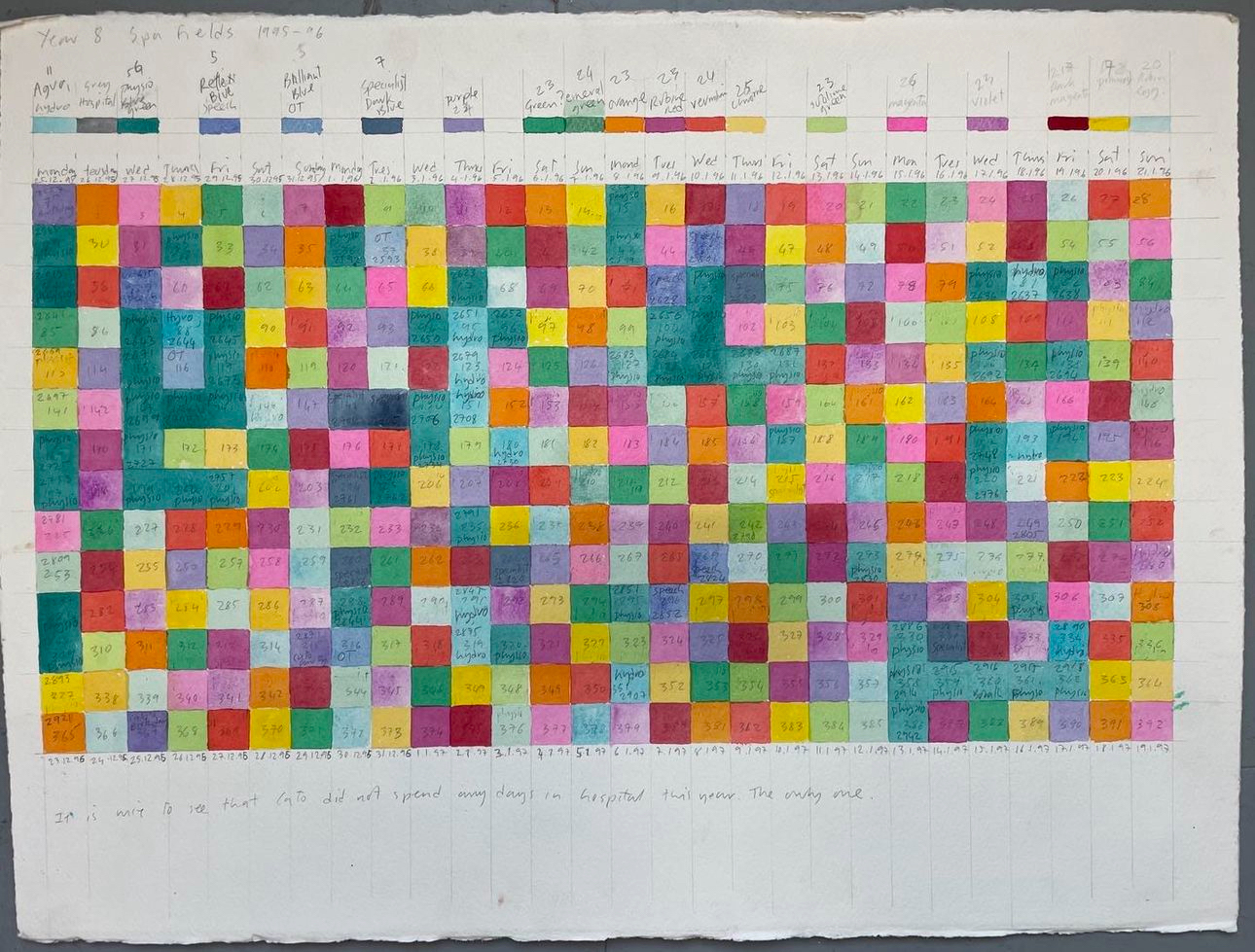

Fig.1. Plan for Cato Mural, Year 8, Spa Fields (2023)

Douglas’ work is a plan for a mural commemorating the life of her late son. I haven’t been able to discover much information about the work other than the short statement that Taylor makes in the video where she describes that Douglas uses a documenting/ drafting system to relate colours to specific occasions/ moments of her son’s life. The details of Douglas’ system are immaterial in relation to my output though: seeing images of the piece, merely seeing a system of colours and numbers at play lit a small spark of inspiration in me that caught fire very quickly.

I had become focused in my thinking on finding a way to explore portraiture in relation to this exercise. Seeing Douglas’ work immediately reminded me of the pixels that make up a digital image – and from that realisation, the rest of the concept surfaced very quickly for me.

We are increasingly living our lives and viewing our world through our digital devices. We our curating our daily experiences to construct how we want to be seen by others. There is almost a fear of others seeing us at our worst or at our most vulnerable or lacking – of others seeing us in those moments we regard as less-than. I wanted to comment on this constructed image of ourselves that we share with the world, how we alter and manipulate these images to offer up the best version of ourselves. And I also wanted, in some way, to offer a comparison between the speed and frequency of the production of these tailored visual records of ourselves, how they reflect the fleeting nature of the moments they record, and the traditional art of portraiture, with the time, effort and skill that that requires.

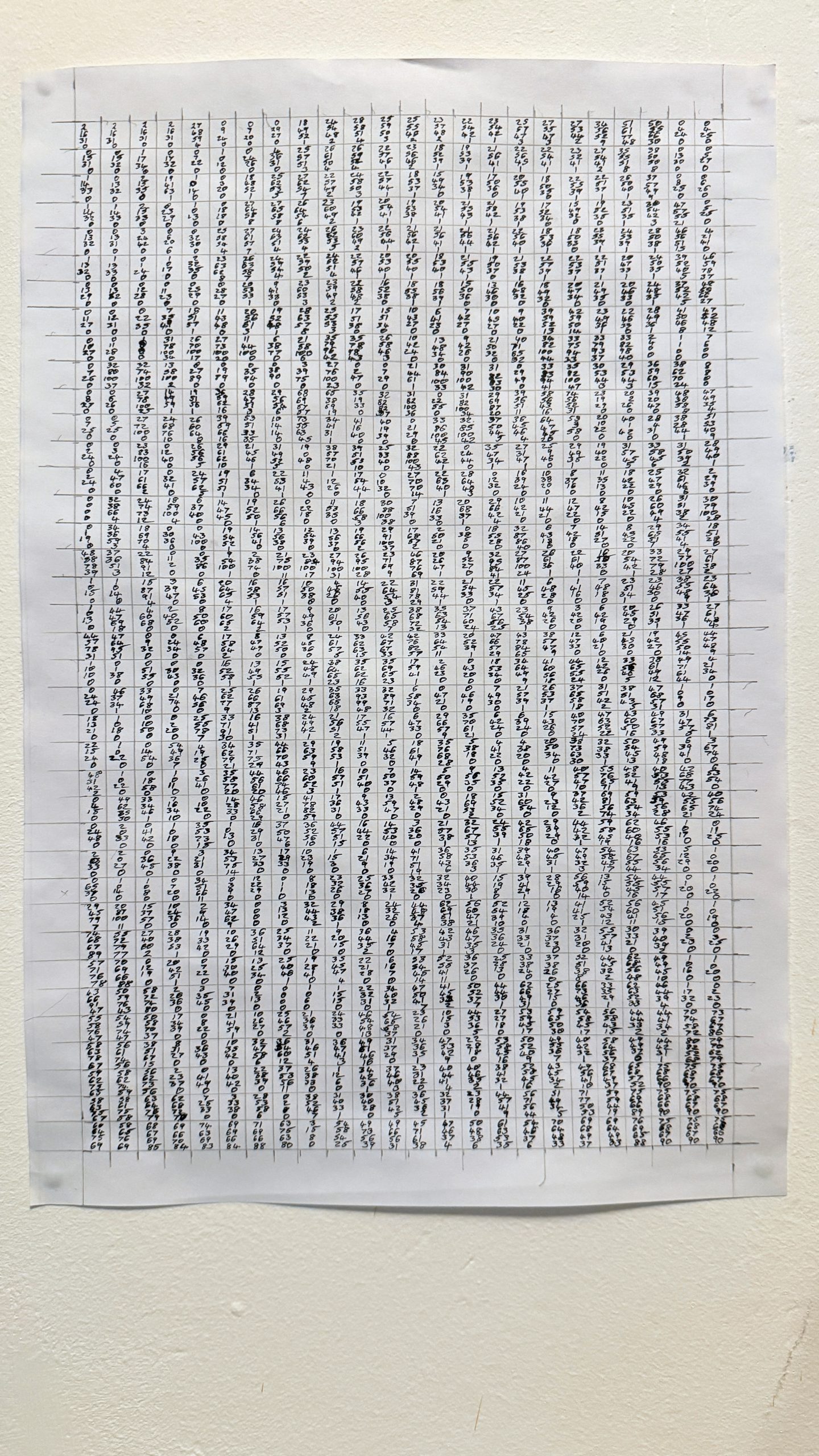

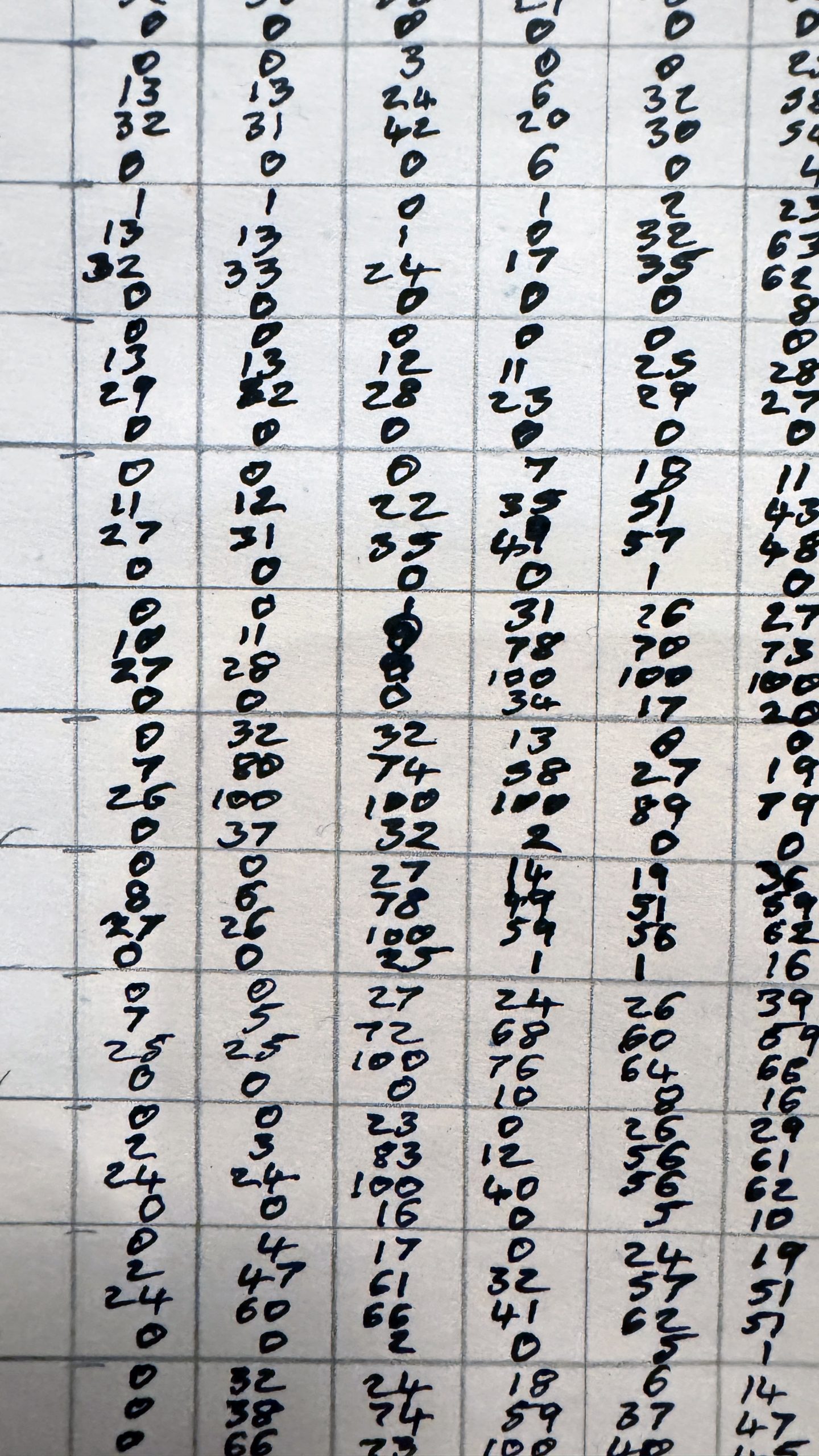

As I mentioned above, this concept and how to realise it arrived very quickly. I decided to reproduce a selfie, but distill it down to the essential components that form a digital image, the pixels. But not as patches of painted colour – that was too obvious (simply put) and a deviation away from the red-thread of the project (text, writing): I would record the pixels in terms of the colour codes, specifically the CMYK values, those required by printers to produce a physical print, as that correlated to the physical nature of paint.

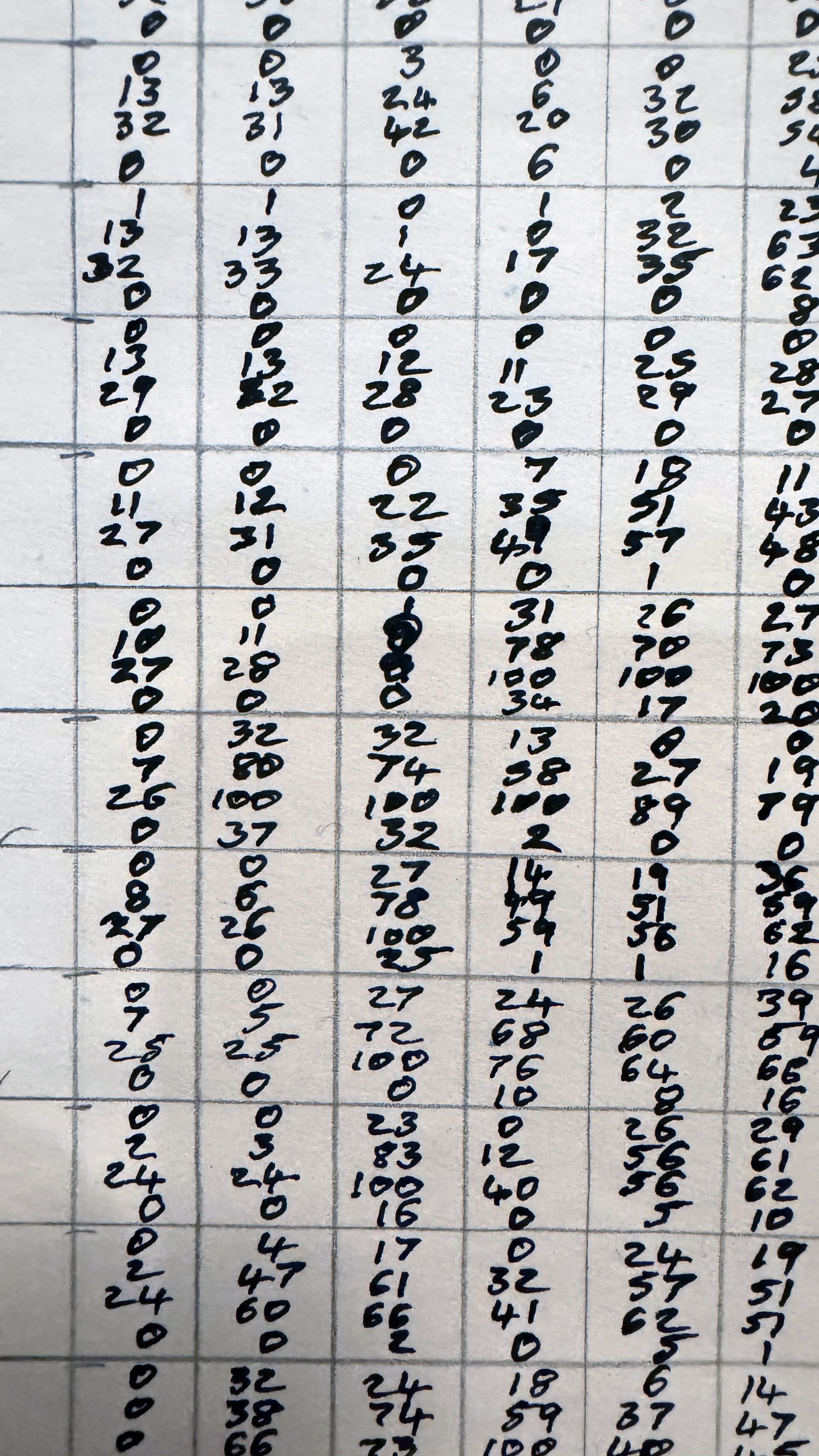

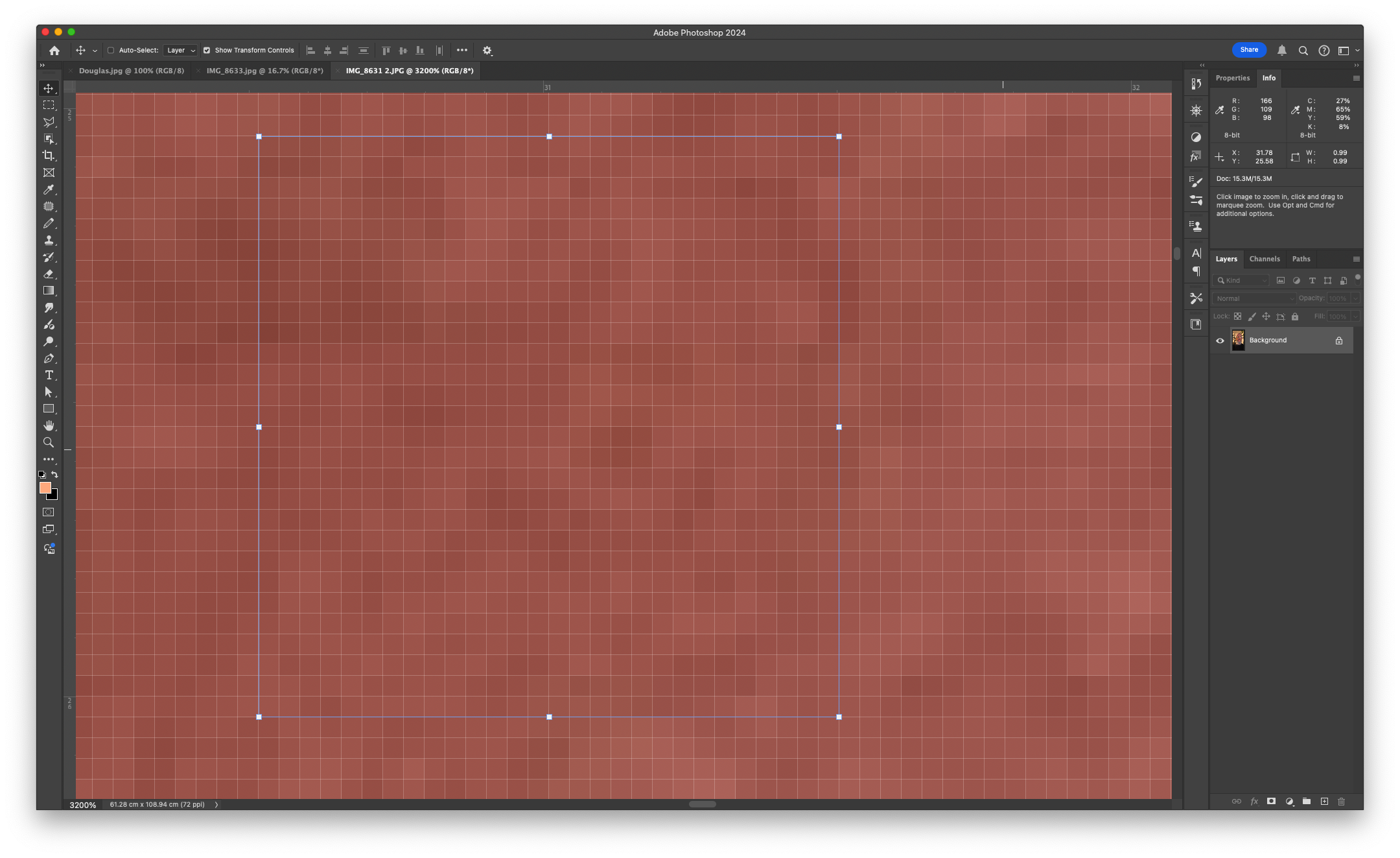

Number of pixels per square cm.

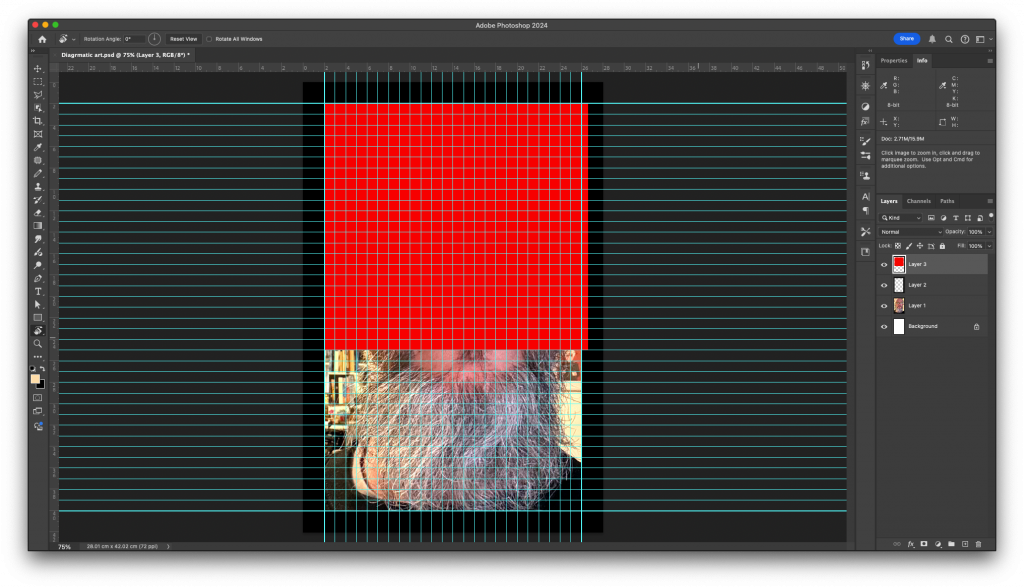

I determined immediately that I couldn’t record every pixel in a single digital photo taken on an iPhone: there were 784 pixels per cm2 in the image I took, which is approximately 715,000 pixels in the complete image. So I decided to divide the selfie into 1cm2 ‘pixels’ and take a single colour sample from within that cell.

It was also important at this stage to consider the paper size I would work on, and match that to the source digital image.

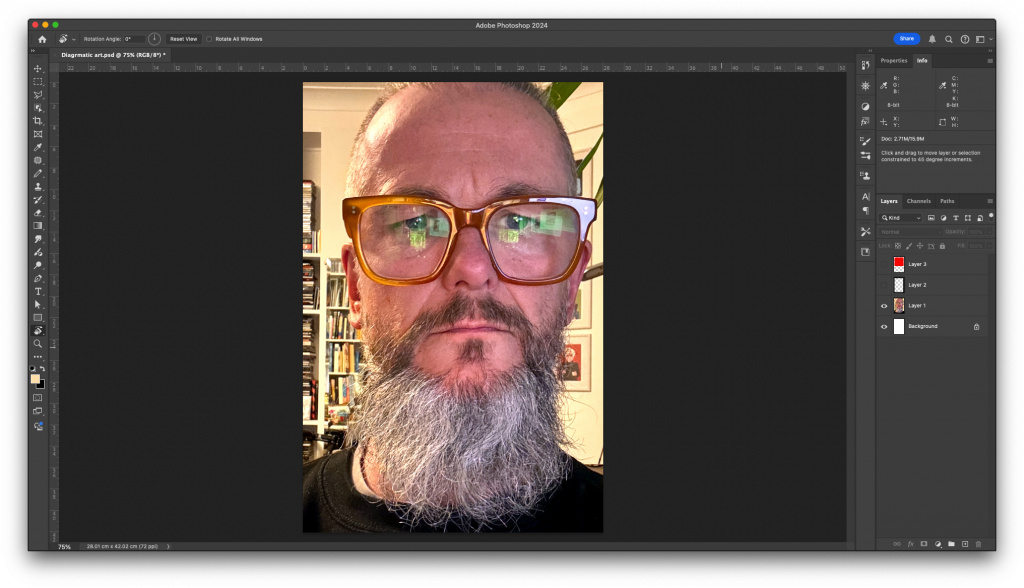

- The original iPhone selfie

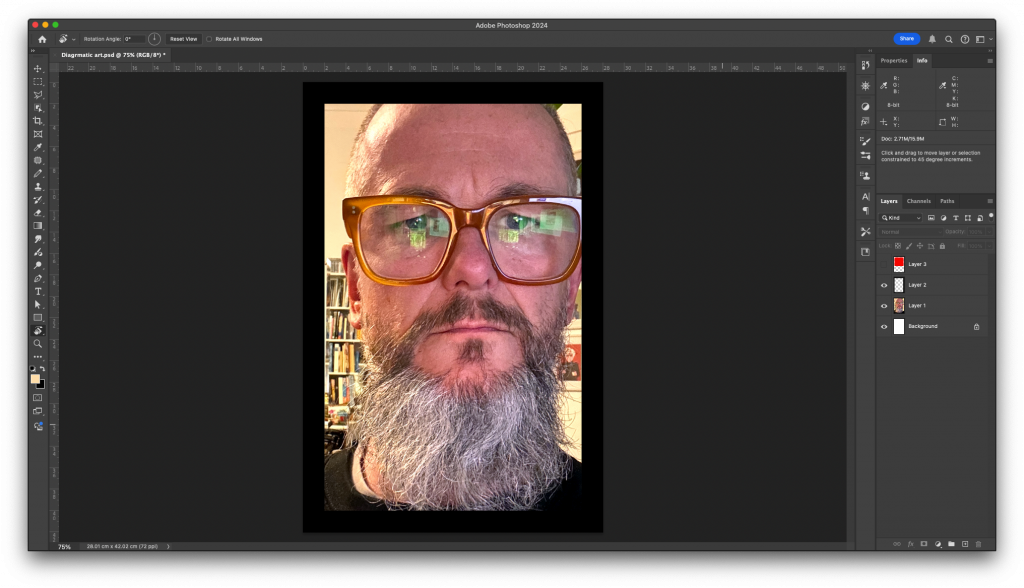

It had been clear to me from the outset that this needed to be large(ish!), though not too big as due to time poverty. A4 felt too small and too easy – the labour of production was an essential element of the concept – so I settled on A3. I also wanted to work on standard 80gsm printer paper, again as a further reflection of the technology that forms a typical part of our lives . I brought the image into Photoshop, recorded its physical dimensions in CM, then correlated that against an A3 piece of paper. There were some differences, so I trimmed the paper and added a frame around the image in Photoshop to align the dimensions.

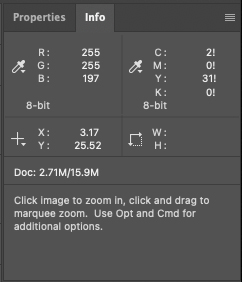

2. Applying a frame to align the image dimensions with the paper

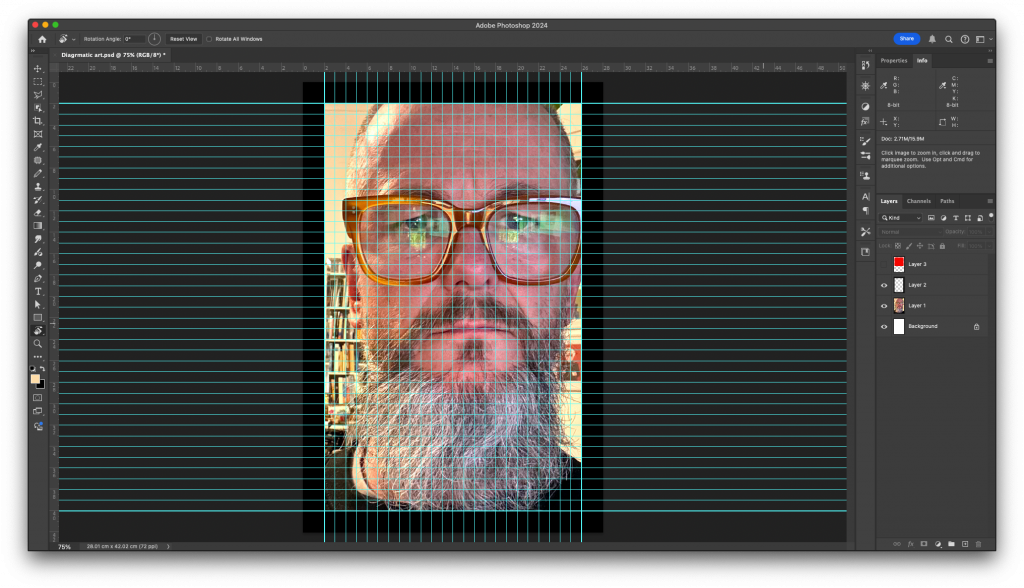

I then constructed a grid of 1cm2 ‘pixels’ over the Photoshop image, and matched that on the sheet of paper in graphite (I fixed this to prevent smudging as I worked): 38 rows, 24 columns – 912 cells in total.

3. Applying a grid of 1cm2 cells over the image

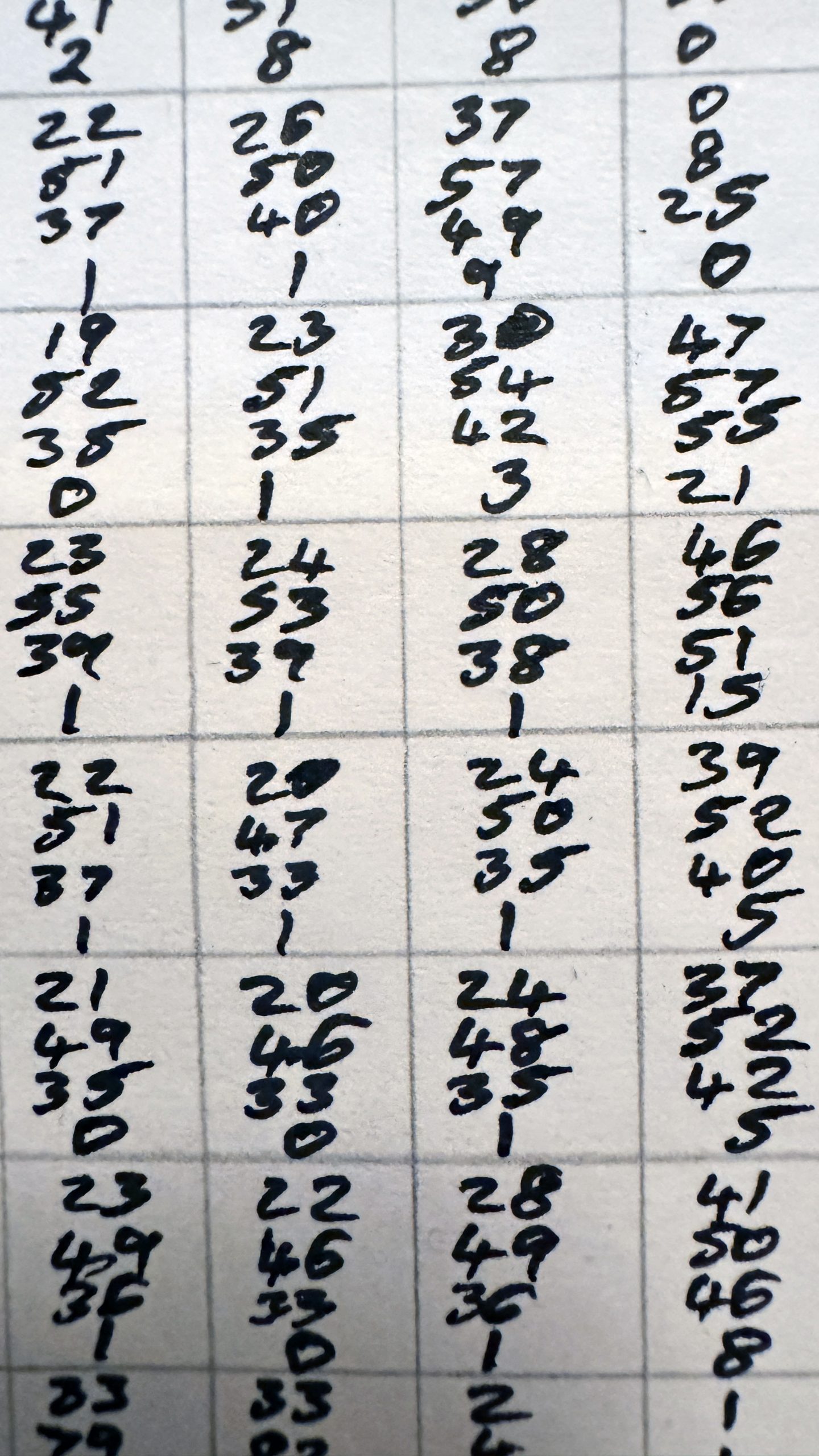

5. Photoshop’s info palette showing a sampled CMYK value top left

It was then about engaging with the work. Working row-by-row, from left through to the right, I would take a CMYK colour sample from within each grid-cell. These I then recorded vertically in the corresponding cell on the paper using a black 0.5mm fineliner pen. It felt important to work systematically, from left-to-right, from top-to-bottom, as this reflects on how we read and write in the West, though, in the final piece, the columnar presentation of the copy is more indicative of some Asian writing formats. To aid with this sequential process I introduced another layer over the image in Photoshop, containing a red block, which I extended downwards each time I completed a row of cells. I also found myself quietly reading out-loud the CMYK codes each time as an aide-memoire in the gap between the sampling and the physical act of writing.

As the process continued, I became more aware of the physical discomfort of the activity. My eyes would tire because of the change in focus between the laptop screen and the paper: my arm from the shoulder to my hand would ache from the repetitive nature of the act. But the discomfort was important as it reflected on the effort of the traditional creative process, specifically the painterly approach to portraiture, as opposed to the immediate, almost effortless nature of the iPhone selfie: the level of effort and time it took to create this piece (around 5 hours) is a reflection on the time and skill it takes to create art, whereas digital devices can generate content that many consider art quickly and easily. That then asks questions about what should constitutes art, if digitally generated content has a place within the artistic canon?

There is in the act of ‘writing the face’ a tangential link back to Neshat’s work and I could also argue a conceptual connection to Michael Craig-Martin’s work ‘An Oak Tree’, which playfully works with the idea of transubstantiation. Craig-Martin asserted that the single most important element of an artwork is belief, the faith of the artist in what they have to say, and the faith of the audience in accepting what the artist has to say.

It was my conviction that I had deconstructed the work of art to reveal its single basic and essential element: belief – that is, the confident faith of the artist in his capacity to speak, and the willing faith of the viewer in accepting what he has to say. In other words, belief underlies our whole experience of art”.

Craig-Martin, 2015:132

The implement I chose to write with imposed an essential characteristic on the work. Even though fine, the 0.5mm pen still offered challenges to writing within each small cell on the paper. I had to judge the pressure I applied to the pen to be able to write readably within each square. Too heavy and the numbers would blur, to light and they would be too faint. I had also to try and control the size at which I wrote the pairing for each of the C,M,Y, and K codes. These physical considerations were the contributors to my physical discomfort, and the quality of the written output. The ‘mistakes’, the blurring of the writing, the smudging etc – are all performative reflections on the creation of this self-portrait

4. Keeping track of which rows had been colour sampled

The finished work: ‘I’m more than the sum of my parts (self-portrait)‘

There is plenty of opportunity for me to continue exploration of this conceptual approach. Obviously, different self- or other portraits, finer grids, larger scales, using this as an instruction document for creating a painting, digital or otherwise. I have also considered audience-artist collaborations, CMYK codes on post-its, stuck to a wall, encouraging the audience to reorganise the post-its, then create a painting at a specific point in time after some rearrangement. This again would ask questions of how we see each other, how we present ourselves to the world through the digital channels and devices we have access to. The issue I have is this feels so far from the creative practice I envision for myself. It feels too ordered, systematised, un-painterly, restrictive, un-emotional, uninvolved with the physical properties of the materials themselves: all contrary to the elements that have most interested me. Perhaps that’s my next challenge, how to sync the two sets of dimensions.

‘I’m more than the sum of my parts (self-portrait)‘ (Detail)

‘I’m more than the sum of my parts (self-portrait)‘ (Detail)

List of References

Craig-Martin, M (2015) ‘An Oak Tree’ In Craig-Martin, M On Being an Artist. London: Art Books Publishing Ltd. Pp. 128-133

List of Illustrations

Fig.1. Douglas, E (2023) Plan for Cato Mural, Year 8, Spa Fields [Watercolour on watercolour paper] At: https://www.instagram.com/emmadouglas_a_tender-walk (Accessed 21/10/24)